Share

This story was originally published by Range

While Eduardo Muñoz Lara was working in an apple orchard in Othello on an H-2A farmworker visa, his wife, Laura Sandoval, was more than 2,400 miles away in their hometown of Ciudad Victoria, Mexico.

Separated by that distance and wanting to see her husband’s face, Laura video chatted Eduardo early the afternoon of October 11, while he was in isolation due to COVID-19 protocols. He hadn’t taken a COVID test because he was asymptomatic and because, according to Laura, workers were told tests would cost them $200.

When Eduardo, 38, answered the call, Laura immediately realized something was wrong. Her husband was having a stroke.

With Eduardo alone in his room, Laura says she felt helpless. “I was on the other side of the phone, and there wasn’t much I could do except scream for somebody to help him.”

She says it took hours before anyone found Eduardo and called an ambulance.

Eduardo and Laura’s story is terrifying, but it’s hardly unique. COVID-19 cases in Washington’s agricultural communities have skyrocketed in recent months. Many essential workers are uniquely vulnerable to the virus: Hospitalization rates among Hispanic individuals in Washington with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases are almost six times higher than in white populations, and their death rate is 3.5 times higher, according to a Department of Health report.

In 2020, the Department of Labor and Industries (L&I) inspected 422 agriculture businesses and found 517 violations. Of the total inspections, 261 were COVID-19 related, resulting in 68 safety violations.

L&I did not immediately provide data on how many individual businesses were fined and how many were fined multiple times, but an agency spokesperson confirmed that about 60 percent of all infractions involved “serious” COVID-19 violations. There have been no recorded complaints against Eduardo’s employer at the time, Washington Fruit and Produce Co.

As of February 11, there have been 152 reported COVID-19 outbreaks in Washington state agriculture settings, warehouses, and employer-provided housing, according to a DOH report.

The risk was evident from the very beginning.

On April 16, 2020, near the beginning of the pandemic, farmworker unions and advocates filed lawsuits against the state for failing to protect farmworkers. On Dec. 15, Eduardo and his attorney, Carmen Hargis-Villanueva, filed a workers’ compensation claim that alleges his stroke was caused by the COVID-19 that Eduardo says he contracted in his employer-provided housing.

The eight months between those two filings demonstrates how little has been done to create and enforce rules to protect farmworkers, says Ramon Torres, president of Familias Unidas Por La Justicia, an independent farmworker union based in Washington. “Workers shouldn’t need to make hundreds of calls to L&I for them to be protected,” Torres says.

For now, the only recourse for many workers is to file a claim after harm is already done.

On Feb. 3, L&I agreed Eduardo’s claim was valid, and instructed the company to cover his medical bills, says Hargis-Villanueva, a staff attorney with the Northwest Justice Project. The family hasn’t seen the full bill for Eduardo’s medical treatment, but the right side of his body is paralyzed, and his physical therapy alone amounts to about $165,000.

“A farmworker who contracts COVID-19 at work through no fault of his own, because the employer failed to keep him safe, should not have to suffer those consequences, especially when they pay for [medical] coverage with their salary,” Hargis-Villanueva says.

The company — Washington Fruit & Produce Co. — has yet to comply with the order, Hargis-Villanueva says. Under state law, Eduardo can request that the company is penalized for every two-week delay, she adds, and the company can choose to appeal L&I’s decision to the Board of Industrial Appeals.

Not an isolated incident

Torres, who is a farmworker himself, says union leaders spent the summer and fall season visiting work sites all across the state and found many were not in compliance with safety protocols like social distancing or providing proper sanitation. This prompted the union to file complaints on behalf of workers who were too scared to file themselves.

The fear is justified. A Yakima agriculture worker was fired after complaining about working conditions, Torres says, and even when the state finds a violation, the punishments amount to a slap on the wrist. “We’ve seen this time and time again,” Torres says, “People have so much fear that they’d rather work shoulder to shoulder than complain.”

Not only are companies still failing to enforce rules aimed at keeping workers safe from COVID-19, Torres says, the union regularly fields calls reporting that employers are charging workers for PPE, not enforcing social distancing protocols, not properly sanitizing, and not informing workers when they are exposed to COVID-19.

Torres says many workers reach out to the union when, after testing positive for COVID-19, they are simply fired rather than being granted a two-week isolation period.

The plight of the estimated 23,000 H-2A workers in Washington state is dire, Torres adds. Many have reported being intimidated into completing unreasonable quotas and threatened with being “sent back” if they didn’t meet them.

Arriving to the U.S.

On Oct. 11, Eduardo was taken to the Othello Community Hospital and then transferred to Spokane’s Providence Sacred Heart Medical for emergency brain surgery.

Doctors were puzzled as to what induced the stroke, because Eduardo had no preexisting health conditions, Laura says. After he tested positive for COVID-19, she adds, the doctor suspected the virus was the cause.

Laura landed in Spokane the day after her husband was hospitalized, leaving their two younger children with family. She says Washington Fruit & Produce Co. offered to help her get a visa, but she already had one. They paid for her flight instead.

But as soon as she stepped off the plane, Laura says, she was on her own, and the company initially no longer returned her calls. She credits Spokane community leaders with helping her navigate the American health care and legal system.

Hospital employees referred Laura to Jennyfer Mesa, activist and cofounder of Latinos en Spokane (LES), a nonprofit organization that provides assistance and resources to the Latino community. The organization helped Laura find translators, housing, and legal assistance.

Anngie Zepeda, LES program manager, led efforts to get Eduardo the necessary legal assistance to fight his case. At the same time, LES Community Comadres, led by Lupe Gutierrez, helped with translations, paperwork and delivered food every day.

This isn’t the first time Mesa has come across a situation like Eduardo’s. “It’s infuriating to see there’s a systemic problem with essential workers, and it’s borderline racist how they’re able to bring people to work and discard them at will,” Mesa says. “These companies are betting on the fact that [workers] are alone here, and they’re taking advantage of that. They didn’t think that they were going to get help, and [the workers] were going to get an attorney.”

But Eduardo did get help.

After spending 12 days in a hotel room paid for by the Providence Foundation, Mesa invited Laura to live with Mesa and her family for the rest of the month as they figured out what to do. As resources dwindled, Mesa put out a call seeking anyone who might be able to take Laura in as her husband’s care continued.

Nikki Lockwood — a Spokane Public Schools board member — and her husband, Bill, shared their home with Laura from November until her husband was discharged in December. Lockwood is Mexican-American, and says she is well aware of the disproportionate rate of COVID-19 faced by communities of color, as well as the barriers to care and justice that come along with it.

“I just felt like we were going to have to do more than advocacy,” she says. “I knew this was going to be a tough road for [Laura] with all the barriers to access help, and this was one little way I could help. I also knew this was just one story of many.”

After Eduardo’s release from the hospital, the couple began staying in an ADA-accessible hotel close to the hospital, thanks to funding from the Spokane Immigrant Rights Coalition.

The claim and response

Under federal law, the H-2A program requires employers to carry workers’ compensation insurance. If an employee gets COVID-19 at work, they can file a workers’ compensation claim, Hargis-Villanueva says.

Washington Fruit & Produce Co., where Eduardo had been working, is self-insured through Eberle Vivian. Companies that are self-insured can have more of an incentive to make the claims process more difficult, Hargis-Villanueva says.

Eberle Vivian asked L&I to deny the claim Eduardo filed on Dec. 15, and on Jan. 7, the department said it needed more information to decide the claim, Hargis-Villanueva says, though L&I directed the insurance company to pay Eduardo for his time off in this “in-between period.” On Jan. 21, L&I authorized the claim and instructed the company to pay for Eduardo’s medical bills and other benefits afforded to him under the state’s Industrial Insurance Act, Hargis-Villanueva adds.

Washington Fruit & Produce Co. formally protested the decision on Jan. 28, asking L&I to reconsider, but Hargis-Villanueva says the department affirmed its decision on February 3.

The housing conditions

Katherine Ryf, spokesperson for Washington Fruit & Produce Co., said in a prepared statement that the company developed a COVID-19 safety plan and has complied with all safety guidelines set by the CDC, Gov. Jay Inslee, L&I, and state and county health departments. “Nothing is more important to us at Washington Fruit than the safety and health of our workforce,” Ryf wrote. “The guidelines were successful in preventing any large outbreaks at our facilities.”

But Laura says she had caught glimpses of her husband’s living conditions during many of their video calls, and believes there was no room for the workers to socially distance.

There were three workers living in the same room initially, she says. Two slept in a bunk bed, while the other slept in a separate bunk. Bunk-bed rules had allowed employees to sleep directly over another worker as long as they slept in opposite directions.

Farmworker advocates protested the DOH rules allowing bunk beds, claiming they would increase risk for infection. Republican leaders in Eastern Washington signed a letter calling on Inslee to allow more flexibility in worker housing, arguing that rules should be revised because they would disrupt the state’s economy. Emergency rules went into effect May 18, 2020, but bunk beds were still allowed in some cases.

“We were only asking for protections, and the state basically said no,” Torres says.

Laura made sure Eduardo left Mexico with N95 face masks, sanitizing gel, and aerosol. “I saw many occasions that I thought increased the risk for infection and I realized that’s how he must’ve gotten the virus,” she says. “I became angry because I thought ‘How could they be so inhumane?’”

Ryf’s statement says workers were housed two per room after adjusting to new guidelines, and argues that Eduardo could have contracted COVID-19 outside his housing. Laura says she believes her husband contracted COVID-19 before he was moved to a room with only two workers.

Eduardo told Laura one of his roommates had been taken to isolation, but he and his other roommate were never told why and were not informed about possible exposure to COVID-19. Shortly after, he was taken into isolation, where he suffered the stroke, Laura says.

Ryf says the company has administered free COVID-19 tests to employees under the CARES Act, but Laura says Eduardo and other workers were told COVID-19 tests cost $200, so he never asked for one.

“I don’t know how these people can sleep so soundly without understanding what they have caused,” she says. “Of course we knew the risks before coming, but we never imagined it would be to this degree.”

Barriers to reporting COVID-19 violations

An L&I spokesperson says the department relies on complaints to investigate alleged violations. The department typically sends a letter notifying the company that someone made a complaint, instructing them to fix it. If the problem persists, the department will carry out an inspection.

But many workers are scared to file official complaints, Torres says, because it puts them in a tough situation as they weigh their safety against a paycheck to support their families.

Further complicating matters, many farmworkers only speak Indigenous languages, such as Mixteco or Triqui, and L&I cannot help them, Torres says, a gap Familias Unidas Por La Justicia is trying to fill by offering Indigenous language services.

The exploitation of farmworkers didn’t begin during the pandemic, Torres says, but it certainly made a century-long problem deadlier. Last summer, hundreds of warehouse workers in Yakima went on strike because of unsafe working conditions.

“What do we have to prove so they listen?” Torres says. “We had almost 1,000 workers on strike this summer, and these companies are open like nothing happened. Most haven’t been fined, and they continue to spread the virus just like before.”

For Torres, it demonstrates a clear issue with employers not enforcing safety rules. This isn’t an issue particular to a couple orchards or a few packing warehouses, he says—it’s happening across the state and beyond.

Torres says L&I needs to be more proactive in policing company practices as opposed to waiting for hundreds of calls to carry out an inspection. The system for reporting safety violations needs to be simplified, he says, and vulnerable workers deserve support from state agencies in the form of clear, firm rules followed with rigorous enforcement.

Agriculture is the economic lifeblood of much of Central and Eastern Washington, but that playing field is brutally uneven, Torres says, favoring the profits of agribusiness over the health of workers.

The Long Road to Recovery

Today, Eduardo is still confined to a wheelchair and struggles to speak, Laura says.

The money he earned as an H-2A worker was the family’s main source of income, supporting Laura and their three children, the youngest of whom is 10. The couple worked several jobs to sustain themselves in Mexico, but Laura says that work won’t be enough.

This is not a short-term crisis for the family. Because of the significance of his injuries, doctors told Laura that Eduardo will probably never work again.

“I’ve spent many of my days in tears just because the weight of it all comes bearing down on me,” Laura says. “We’ve suffered a lot, but I tell him he’s still alive and that’s what matters.” All Laura wants now, she says, is for the company to understand the severity of the situation, to pay what they have been awarded, and to make sure no other family goes through what she and Eduardo have.

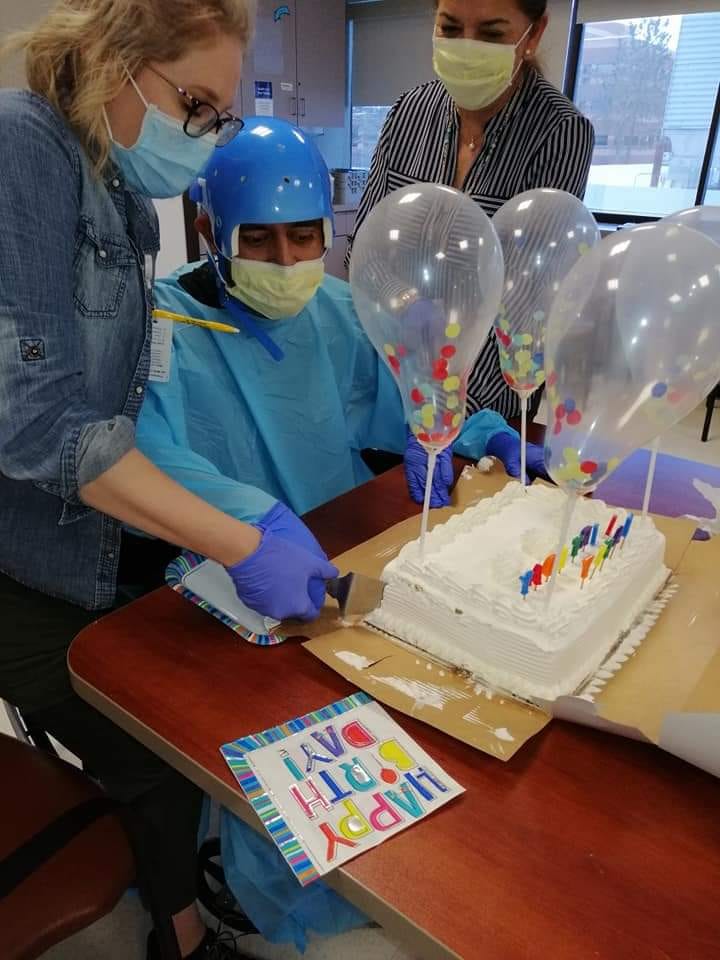

Last Wednesday, Feb 10, Eduardo and Laura flew back home with the help of the Mexican consulate. Community organizers in Spokane are raising money for the family’s living expenses and an electric wheelchair for Eduardo.

You can donate to the gofundme here.

Daisy Zavala translated interviews with Ramon Torres and Laura Sandoval from Spanish to English.