Share

The Killing Floor is a moving recognition of workers and the histories of the overlooked. You’ve probably heard of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, a classic novel that exposed the evils of capitalism and exploitation of workers in the meatpacking industry. The Killing Floor, which debuted in 1984, is also an exposition of the fictitious American Dream, but through the lens of race. It was restored in 2019 in honor of the 100th anniversary of the Chicago Race Riot of 1919. More than a hundred years later during the Movement for Black Lives, it speaks to the violent realities experienced by Black people every day. Criticism of the George Floyd uprisings included the common plea of “violence doesn’t solve anything.” But where exactly does violence begin? Don’t daily, persistent instances of harm enacted by employers count as violence?

The whole film had me in a prolonged shudder, waiting for a moment I could rest and safely take a breath, a moment that never comes. Violent shots of knives hacking away at meat serve as harsh visuals mirroring the violence being done to workers when employers deny them their rights. Blood pooling on the cold slaughterhouse floor mirrors the blood spilled on the city streets outside. The film hints at tensions that culminated in the Race Riot of 1919, a weeklong conflict started by white folks during a time of great social changes and economic hardship.

The city was on edge, suffering from a heat wave and a summer of racial violence against Blacks who crossed into white spaces. On July 27th, a white man threw a rock, killing a Black teenager who had crossed the color line while swimming at the beach. A weak police response led to an explosion in beatings, arson, shootings, brawls, and more violence by white gangs. In the film, the main character Frank Custer must travel through white neighborhoods where Blacks have to “watch their step.” When the riots begin, the militia must come in to help Blacks make it to their jobs so they don’t lose their source of income. Survival for Black people has always meant hypervigilance, especially during a pandemic when racial disparities are affecting Black, Indigenous, and other people of color the most.

We should all be realizing the importance of protecting workers in the meatpacking industry. Had I seen The Killing Floor before the pandemic, this reality probably wouldn’t have hit as hard as it does for me now. Last April, former president Donald Trump invoked the Defense Production Act so that meatpacking plants could remain open. Data shows that workplace exposure in meatpacking plants accelerated community spread across the United States. The pandemic’s impact on meatpacking plants includes tens of thousands of cases and hundreds of deaths. This group of essential and in many cases immigrant workers are vulnerable and undervalued. Workplace deaths are going unreported.

That’s why I appreciated that the characters were based on real testimonies from working people in a meatpacking factory. The cast, crew, and production staff deferred half their wages to support production and many Chicago locals and guilds contributed to the film. Those who supported the film thought of it as a way to fight back against the Reagan administration’s attack on the labor movement.

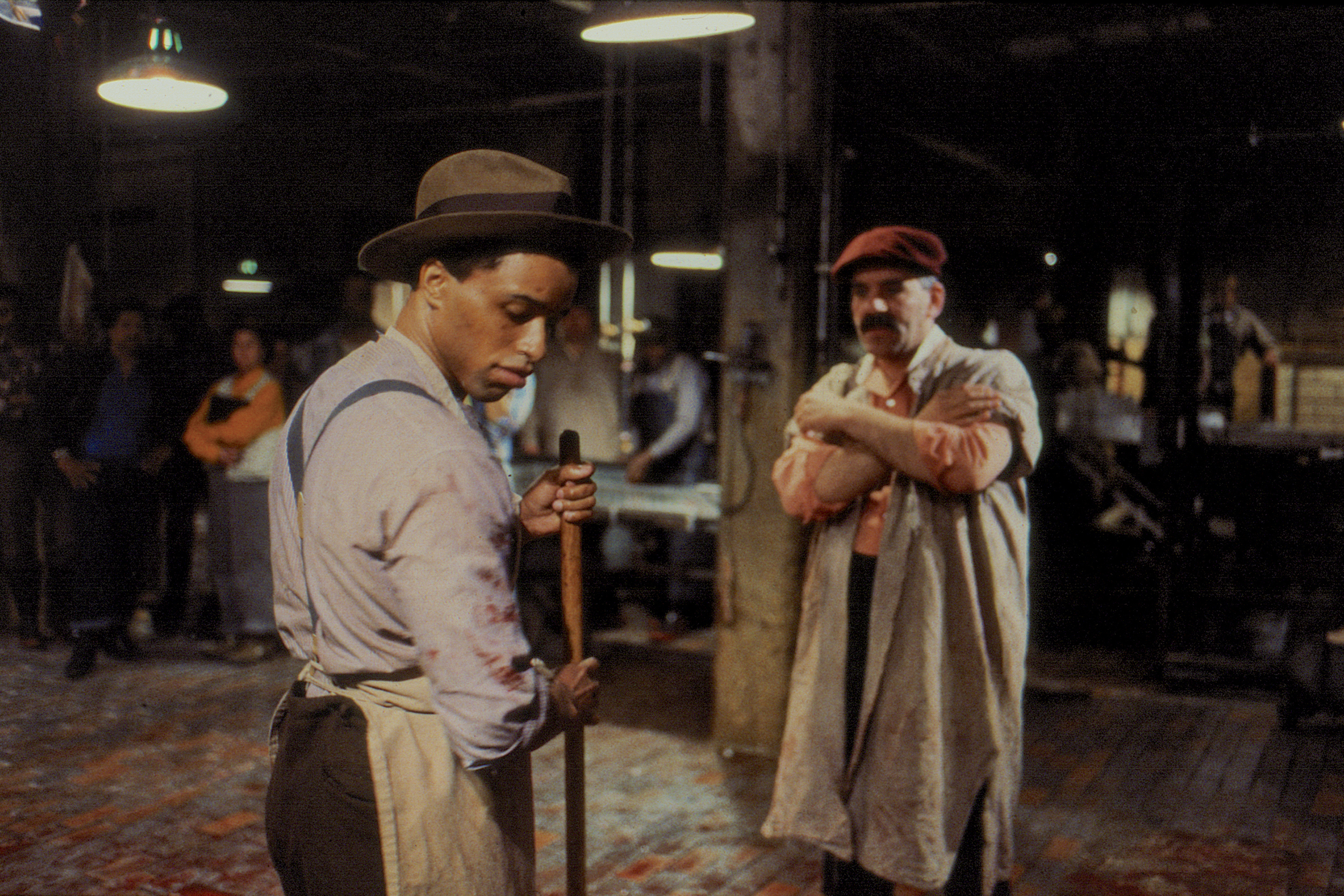

The film begins when Frank, a Black sharecropper, and his best friend Thomas Joshua move from the south to find work and make a better living in Chicago. They find jobs in the Union Stockyards working for a meatpacking company. Frank works on the killing floor of the slaughterhouse where he cleans up blood and bits of cattle. He saves money so his family can join him in the city. Thomas struggles working at the slaughterhouse and eventually joins the army and goes off to war.

Early on, Frank wonders, “how are you supposed to work with folks you couldn’t understand?” How are we supposed to work with people who don’t speak the same language as us or share the same culture as us? How is solidarity built across these divides? The film scratches the surface of answering these questions. The theme of race relations within labor organizing is boiled down to simple respect and friendship. At being invited to join the union, Frank says, “I ain’t gettin in no white man’s fight.” But throughout the story, he comes face to face with the power of collective action and how it can benefit all workers. He joins and becomes a leader and makes friends. He focuses on recruiting other Black men into the union, but this puts him at odds with the Black workers who see it as a white man’s fight. He can’t convince all of them, and by the end of the film, he is ostracized by his community.

When the war ends, workers return expecting to have their jobs back and the employers try to use race to break up the unions. The unions lose influence. There’s no happy ending to this story of early labor organizers, but the seeds of liberation, which grow into the reforms and benefits established in the 1930s, are planted. I wonder what seeds are being planted today, as history seems to repeat itself.

You can feel the build up of never ending grime and gristle underneath your fingernails and a deep ache growing in your bones as the scenes unfold in The Killing Floor. It reflects the dreary and relentless existence of workers under racialized capitalism. Any lighthearted moments quickly give way to the strains and struggle of industrial food production. Being a millennial already critical of the meat industry, some scenes, which were filmed in an actual slaughterhouse, made me never want to eat meat again. It also made me question how much progress has actually been made in the last century.