Share

When Samie Burnett’s infant daughter became sick and hospitalized two years ago, she had to choose between taking time off work as a tutor in a school and working virtually.

“I literally clocked into work from my phone, and was doing classes from my phone while in the hospital waiting to be released. That’s not okay,” she said at a rally for paid leave at the Minnesota state capitol.

On Wednesday, Gov. Tim Walz gathered supporters to celebrate a $72 billion “One Minnesota” budget, including a paid family and medical leave bill that will allow many workers to take up to 12 to 20 weeks off non-consecutively, depending on their reasons for taking leave, and receive partial wages. The program, which will start in 2026, will be modeled after the state’s unemployment insurance program. It will be funded by a tax on employers and their employees at 0.7% of each paycheck, half paid by the employer and half by the employee.

The bill is notable for its inclusive definition of family that provides protection for LGTBQ+ workers and their families. In the policy, the definition of family member includes “an individual who has a relationship with the applicant that creates an expectation and reliance that the applicant care for the individual, whether or not the applicant and the individual reside together.”

According to Pride at Work, an organization that represents LGBTQ+ union members, many benefits negotiated by unions, including leave policies, are based on outdated definitions of marriage and family. Although same-sex marriage is legal, many LGBTQ+ families are not based around marriage.

Gender Justice, a Minnesota organization fighting for gender equity that supported the bill, praised the inclusive language in a statement last week to Workday Magazine.

“We hear from people every day who have faced discrimination based on their gender identity and/or sexual orientation – in the workplace, at home, and in public spaces,” said the organization. “Although policy change is only one piece of the larger puzzle of equality, ensuring that all Minnesota families have the same protections under the law is a powerful signal that discrimination and exclusion are against Minnesota values.

“Further, beyond the inclusive family definition, Paid Family and Medical Leave is a huge step for gender and health equity in Minnesota,” the group continued. “The program will support mothers to remain in the workforce, help to reduce the pay gap, and help to break down outdated gender roles by equally supporting men as fathers and caregivers.”

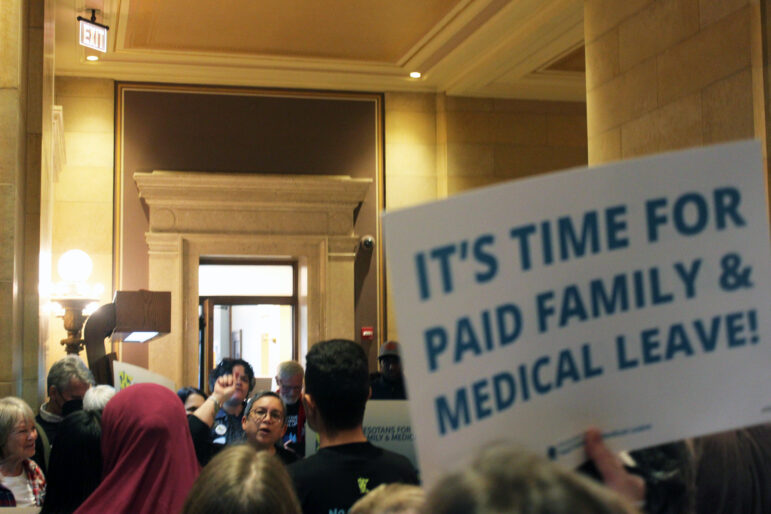

A coalition of health, faith, business, labor, and community groups supported this legislation, which has been in the works for years, and rallied at the capitol on the day of the Senate’s debate.

“Families come in all shapes and sizes,” said DFL state Sen. Nicole Mitchell during the Senate debate. “As a single mother and foster parent, I appreciate the inclusiveness of the definition of family. If you say you want to help mothers and families, that’s exactly what this bill will do!”

Labor unions, which evoke a sense of family and togetherness, have the bargaining power to negotiate paid leave into contracts and are able to support legislation providing paid leave at state and federal levels that includes workers who aren’t union members or traditional employees.

“In the state of Minnesota, no matter who you love or where you live, you choose to be part of a family. We should have the expectation that everybody falls under this bill,” Minnesota AFL-CIO president Bernie Burnham told Workday Magazine after the rally.

Independent contractors, who are typically excluded from protections like paid sick leave or time off that cover traditional employees, will be able to opt in to coverage just like paid leave programs in other states. A 2020 report by the Urban Institute, a nonprofit research organization providing data on mobility and equity, recommends policy that both meets the needs of workers and strengthens the economy, including social insurance with expanded coverage for nontraditional employees, including temporary, subcontracted, and on-call workers and independent contractors.

The bill creating such a program in Minnesota states that self-employed individuals, independent contractors, seasonal workers, and employees of the United States don’t fall under the definition of covered employment and employee. However, the bill later states that self-employed individuals and independent contractors can file an application to the commissioner and pay an annual premium to become entitled to benefits. Both can elect to be covered by this program, but are defined by different criteria. In the bill, self-employed individuals are defined as “a resident of the state who, in one taxable year preceding the current calendar year, derived at least 5.3 percent of the state’s average annual wage in net earnings from self-employment.” Independent contractors are determined by different factors under Minnesota Rules, part 5200.0221.

The earned sick and safe time policy, which is in the Omnibus labor bill that appropriates spending for economic recovery and new worker protections, is different from paid family and medical leave because it’s for short term absences. Duluth, Bloomington, Minneapolis, and St. Paul already have sick and safe time policies in place, with Minneapolis and St. Paul having some of the broadest definitions of family.

Some employers are required under the federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) to protect their employees’ jobs with unpaid leave, and some do offer paid leave, but those benefits vary depending on the employer. Although FMLA allows employees who work at companies that meet certain criteria to take unpaid leave, advocates say it is limited and has barely changed in the three decades since enacted, even through the caregiving crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, only 24% of private industry workers and 27% of state and local government workers had access to paid family leave in 2022. The U.S. is the only industrialized country in the world without a federal paid leave policy for all workers.

According to Gender Justice, the federal system isn’t enough: “The family definitions provided by programs like FMLA leave too many behind and, in particular, disproportionately harm LGBTQ+ people who rely on and care for chosen family,” the group said.

Working families across the globe experience obstacles and social injuries that prevent them from building economic security, such as price gouging, time poverty, and caregiver discrimination. Some employers evoke a sense of family in the workplace, manufacturing a culture of loyalty and belonging, but their employees run into difficulty when faced with choosing between taking care of loved ones who need long term care and keeping their jobs and wages.

In legislative debate and the news, lawmakers and the press have framed worker protections against the interests of small businesses. MPR News and Fox News released segments on paid family and medical leave quoting the National Federation of Independent Business’s (NFIB) Minnesota state director John Reynolds. According to previous coverage by Workday Magazine, the NFIB positions itself as a nonpartisan, grassroots voice of small business, however, it has a track record of supporting conservative causes, has historically received millions of dollars from right-wing groups and lobbyists, and has been lobbying for the loosening of child labor laws across the Midwest.

Paid leave standards are not equally offered or enforced across workplaces, industries, and professions, but something that has expanded over time is the definition of family. From marriage equality to representation in government and workplaces, the fight for working families from LGBTQ communities to be able to give and access care has been a historical struggle. And, according to an analysis from the Center for American Progress on U.S. census data, 82.2% of households don’t fit into a traditional or nuclear family structure.

Minnesota isn’t the only state trying to fill this gap. The Center for American Progress notes in a fact sheet that eleven other states currently have leave laws. Washington recently became the first state in the U.S. to pass a bill providing paid family and medical leave specifically for rideshare drivers. The city of Seattle made permanent an ordinance providing paid sick and safe time for gig workers during the pandemic. Although the U.S. Congress passed emergency paid sick leave during the pandemic, it was temporary and excluded millions of workers.