In May 2022, workers gathered at the Minnesota state capitol to deliver a “past due” invoice to the state senate for frontline worker compensation.

Share

As the third anniversary of the Covid-19 pandemic passes us by, the Biden administration is seeking to declare an end to the federal public health emergency, along with policies and benefits that provide protection and support for working people who kept the economy open and running during a planetary health crisis. In doing so, the president is leaving the states responsible for addressing gaps and protecting workers.

This is happening as around 72% of people live in areas with substantial or higher transmission, thousands are being disabled from long Covid-19, and hundreds are dying daily. Amid this suffering, the Federal Reserve is pursuing policies to increase unemployment levels in order to curb “inflation.” Governments and corporations have been insidiously prioritizing the recovery of profits at the expense of working people and the environment. Look no further than “Cop City,” where corporate leaders and private equity firms, instead of using their record profits to support the essential worker “heroes” who put their lives on the line during the pandemic, are using public worker pension funds to invest in the militarization of a police force devoted to crushing working people fighting against injustice.

The pandemic has shown us how the political economy we uphold depends on a workforce deemed just as disposable as many of the products we labor to produce, consume, and throw away. This is why the twisted narrative of “no one wants to work” is an incomplete story. We want to work to live, not just survive. We aren’t given the space to cope with this reality when the 24-hour news cycle offers little room for us to pause, process, and heal from loss, leaving us stuck in a perpetual loop of trauma, stress, and despair.

In these cycles of panic and neglect that beset us in times of crisis, working people facing the highest economic and moral injuries are building new compasses that can lead us to a path where nothing and no one is disposable. Building that resilience through cultural storytelling is one way we can improve and defend our material and emotional realities against those who seek to steal our voices and our lives.

I question the social amnesia urging us to learn how to live with a deadly virus the same way we must learn to live with the exploitation of our labor.

Telling a more complete story has never been more important. Some act as if the pandemic is over, and talk about it as if it’s in the past, while acknowledging that our response to it is still ongoing. I question the social amnesia urging us to learn how to live with a deadly virus the same way we must learn to live with the exploitation of our labor.

Of course, many workers are fighting back against this exploitation. We are living during a surge of support for unions, even if overall union density still remains relatively low, with the union membership rate at 10.1%. Amid increasing enthusiasm about unions, and backlash to that enthusiasm, congressional lawmakers reintroduced Protecting the Right to Organize Act, and Democrat-led states have been attempting to expand paid family and sick leave, while Republican-led states have been advancing anti-union legislation. We can and should make it the norm to listen to those workers on the front lines of these struggles, and prioritize their wisdom and knowledge, not just leaders beholden to volatile markets and systems of order and wealth that erode wellbeing and democracy.

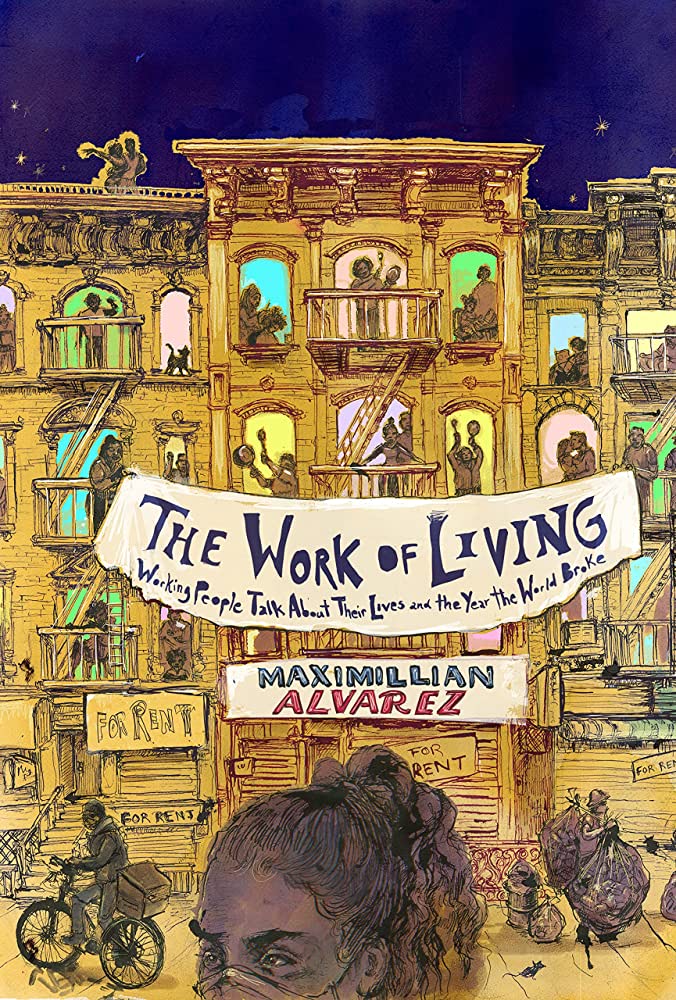

This is why Maximillian Alvarez’s book, The Work of Living: Working People Talk About Their Lives and the Year the World Broke is so important. Each testimony provided in this archive of pandemic stories helps to counteract narratives about the pandemic, memorializes the collective culture we create during times of struggle, and shows how heartfelt and heartbreaking interpersonal drama reflects on our global stage. These stories bundled together encapsulate the moment of class struggle that we find ourselves in today. Not only is this book necessary reading for those in the labor movement, but it’s a compelling work for people who may not be directly involved in social movements, and for any curious reader wanting to learn about what it’s like working in all kinds of industries and places.

The first interview is with Nick Galuppo, a gravedigger. This sets the tone for the rest of the book, sending us straight into the heart of spiritual and material struggle. His story shows how workers are often made responsible for providing a sense of tranquility in society, for hiding the messiness of our everyday transactions. A cemetery, or a “fast-paced construction site for the dead,” is a place where land, bodies, and ritual come together. It’s hazardous work, and during a mass death event, extremely busy. On average, they’d do four or five burials a day. That tripled during the early months of the pandemic.

The next interview is with Rebecca Garelli, an educator-organizer who teaches science to teachers. She takes a scientific approach to organizing when describing and building worker power. Industrial hygienists taught educators about ventilation and aerosolized particles and how to bust myths. What she says about “learning loss” should be shared widely:

“There’s nothing objective or permanent about these things. The standards we teach to, the goals we set for students—–these are social constructs that we have decided to apply to certain grades and age groups, which means we can change them.”

Duane “Chili” Yazzie, a community leader in the Navajo Nation, spoke about the American Indian Movement’s armed takeover of the Fairchild semiconductor plant in 1975. The group was protesting the company’s exploitative practices and abusive business model. They demanded the rehiring of 140 Navajo workers who were laid off, but Fairchild decided to close the plant instead.

Chili’s words about the pandemic are haunting:

“Covid-19 is a thing of nature. It’s not anything mechanical—it’s alive. What I say is: It’s alive with death. To me, it’s a great discipline whip of the Earth, basically punishing the people of the world for the mistreatment, for letting things go to this extreme.”

The rest of the interviews are filled with heavy and intimate knowledge about industry practices of slow death, burnout, and moral injury. Zenei Triunfo-Cortez is a registered nurse and president of the California Nurses Association. Over four decades, she has seen how hospitals have been transformed into assembly lines. Nurses were being asked to reuse masks that were decontaminated in batches. While wearing those masks, they were inhaling the cleaning chemicals used on the masks and experiencing headaches and migraines. They were able to prove to their employer that reusing masks was harmful, but then they had to deal with the overwork created by hospitals circumventing nurse-to-patient ratios, all the while worrying about themselves or their families getting sick and dying.

Alvarez, the editor-in-chief of The Real News, located in Baltimore, Md., is an expert in holding captivating conversation. He also hosts Working People, a podcast devoted to in-depth interviews with workers, including rank-and-file union members and leaders, fighting to bring justice and safety to their lives and workplaces. If you want to learn about any issue in the news, I guarantee you there’s a Working People episode related to it that will inform, delight, and anger you.

As much as I value hearing people speak in their own voices with their unique language choices, pauses, accents, quirks, and cadence, being able to sit down with the words in my hands and consume these stories at my own pace has been a treasure. I was able to record my own family’s experiences of working during the pandemic, which is something I’m cherishing all the more after losing my dad to Covid-19 complications in December 2021. Alvarez also began his journey into movement media after interviewing his family about the 2008 recession. There is so much power in simply being present with each other.

We aren’t meant to make sense of or heal from grief and suffering on our own. Learning about how others are and aren’t making sense of their pain, how they’re coping with that pain through community and self care, organizing, and more, has been nothing less than revolutionary for my spirit as a journalist and human on this planet, alive with death. This is the work of living.