Piotr Szyhalski standing in the exhibit “We Are Working All The Time” at the Weisman Art Museum. Photo by Isabela Escalona.

Share

While walking in the offices of the University of Minnesota Twin Cities campus a few weeks ago, I came across a framed poster hanging on a colleague’s cubicle. “We Are Working All the Time!” it read in an ironic cursive font, in what I initially interpreted as a demonstration from overworked students, or a message from the university’s service workers’ union that narrowly avoided a strike last month. But when I looked closer, I realized it was from an art exhibition that, I would soon learn, deliberately blurs the lines between art and political propaganda.

Piotr Szyhalski’s We Are Working All The Time!, now on view at the Weisman Art Museum through December 31, is the artist’s first major exhibition showing work from his 30-year artistic career. While spanning mediums and decades, the themes of our relationship to work, truth, power, and political violence are consistent throughout his multi-media practice that includes visual art, design, performance, sound, photography, sculpture, and leaflets.

The exhibition is a part of a broader and ongoing conceptual umbrella by Szyhalski titled “Labor Camp.” In a description of the project, the artist’s statement reads, “The Labor itself is the only unchanging criterion of cultural merit. Thus: Suspending all ideological banners, we work.” The framework suggests an ephemeral approach to art by reworking ideas through experiment and exploration. The pursuit of political truth is never a one-time arrival point, but rather, something an artist must belabor again and again with each new iteration expanding on the previous and informing the next. In an interview with Workday Magazine, Szyhalski described Labor Camp as the “ceaseless labor” of the artist, who is always thinking critically, always questioning the dominant narratives, and always creating as a response and alternative way of seeing and interpreting the world.

The pursuit of political truth is never a one-time arrival point, but rather, something an artist must belabor again and again with each new iteration expanding on the previous and informing the next.

Too often, artists will shy away from the stigmatized descriptor of “propaganda”—art that stands firm in its moral messaging, or art that can be stapled to a street sign on a busy street corner (as opposed to work that solely functions within the context of a posh gallery wall). Propaganda art can be looked down upon or not taken seriously as “fine art,” especially when it critiques the power that larger art institutions often represent and benefit from, like corporate sponsors or authoritarian governments.

Szyhalski doesn’t shy away from this taboo, but rather, owns it, studies it, and takes political statements just as seriously as technique, daily practice, and visual appeal. Through this approach, he discards the notion of the role of the artist as a removed, morally ambiguous commentator. For Szyhalski, the artist is a laborer who confronts, questions, and creates through the noise of their time—collectively and endlessly.

A daily practice of documentation and dissent

The exhibit begins with monumental, wall-to-wall, bold, grayscale posters that Szyhalski created as a daily practice to cope with and make sense of the early months of the pandemic—beginning on March 24, 2020 and concluding November 3, 2020. The designs were posted each day on the artist’s Instagram account, accompanied by captions with additional commentary, documenting the collective confusion and fear of the early months of the pandemic.

The posters evoke the early rhetoric present in those uncertain and surreal first days during the onset in the United States. One of the most dynamic aspects of the project is its chronological, day-by-day reactions to the unfolding events of the era: from the constantly switching CDC protocals, to the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, to the tension leading up to the 2020 presidential election. The poster series serves as a daily meditation, as well as a raw, real-time historical documentation of a traumatic and tumultuous time of history.

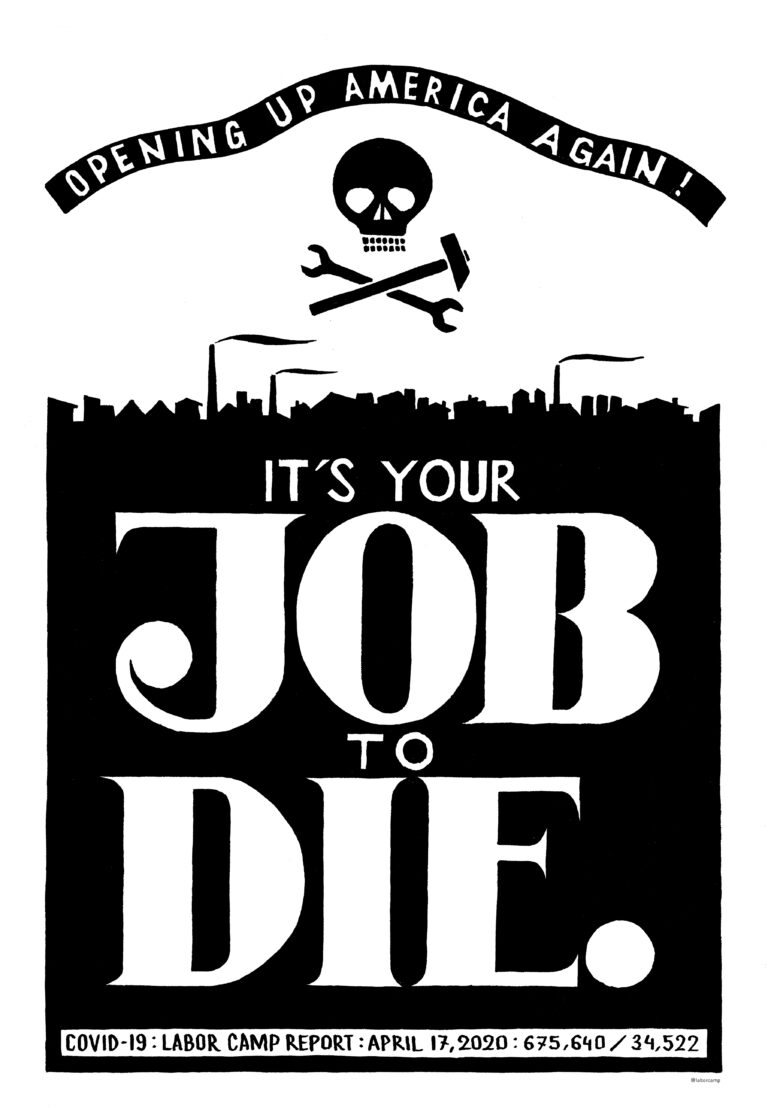

After the initial stay-at-home order in Minnesota began to loosen and more workers were ordered back into their workplaces, Szyhalski responded to the policy decision on April 17, 2020 with a poster (the 25th in a series of 225) that reads, “Opening up America again! It’s your job to die,” in bold lettering atop a cityscape with a skull and crossbones hovering above swapping the bones for a hammer and wrench, eliciting a specific appeal to the safety and wellbeing of workers.

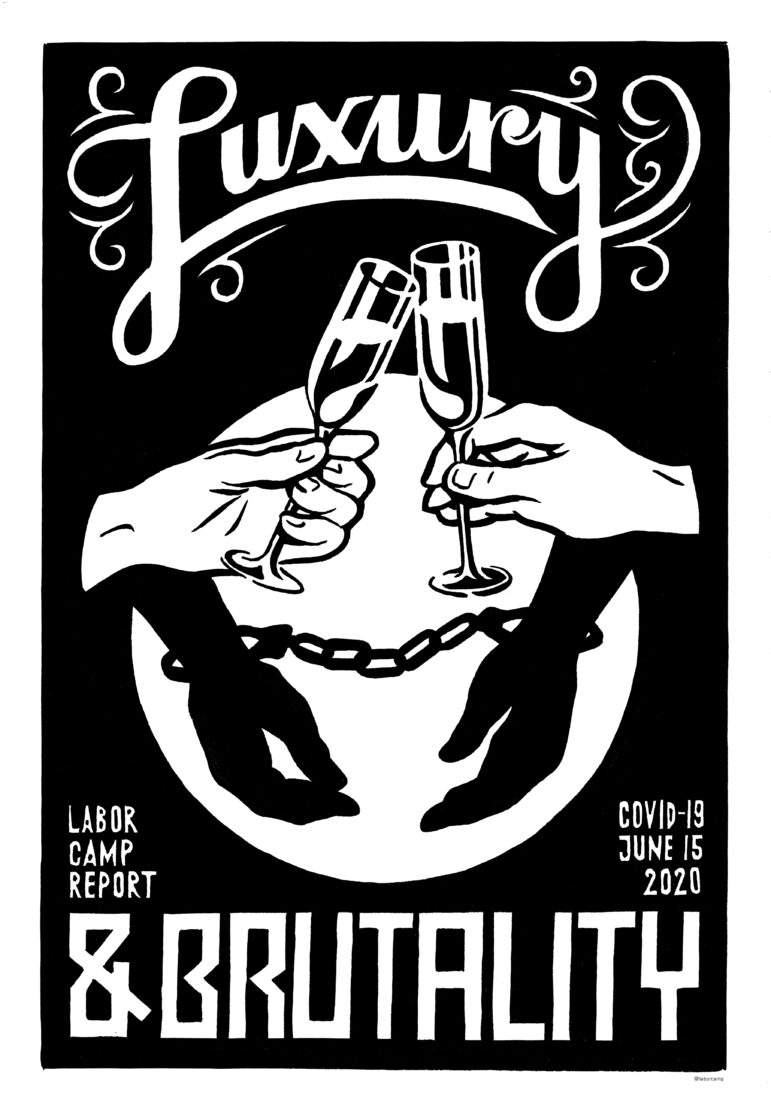

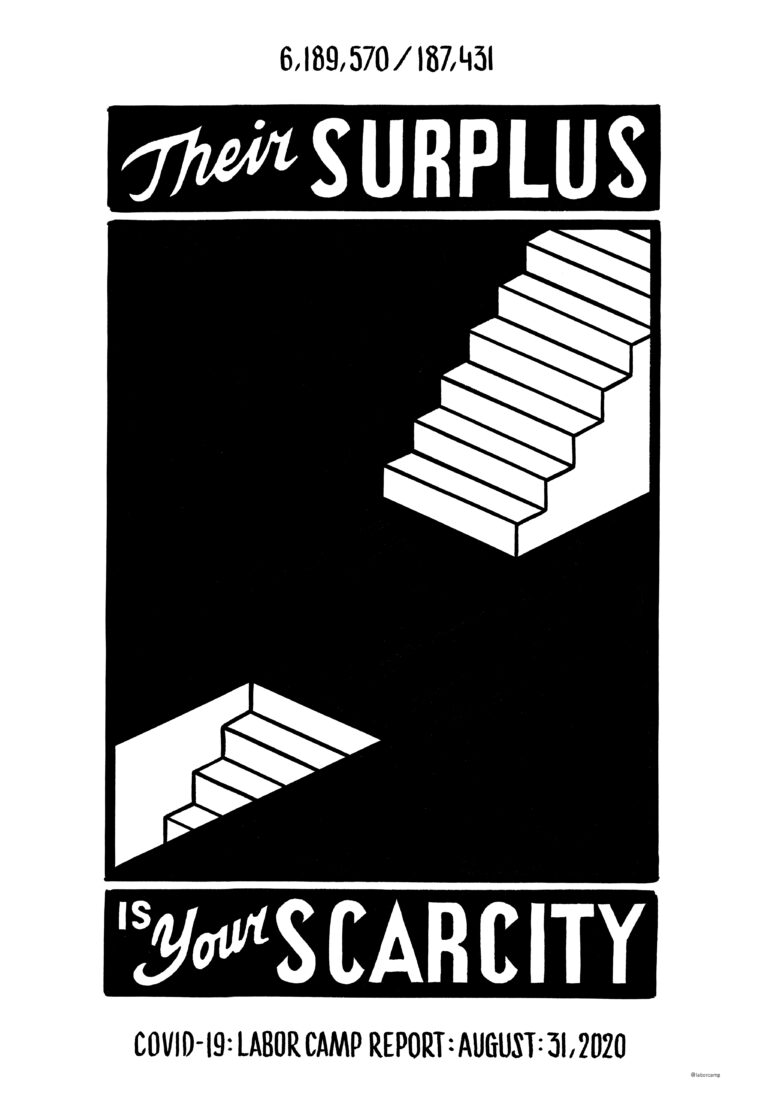

Another poster published on June 15, 2020, depicts two arms clinking champagne glasses hovering over two hands bound by shackles, with the text reading “Luxury & Brutality.” It’s a reference to the operating principle of our time, intensified by the pandemic, that some must die and suffer so that the few at the top can play. A later poster in the series published on August 31, 2020, reads, “Their surplus is your scarcity!” with the imagery of an eerie staircase evoking the decline of one class and the mobility of another.

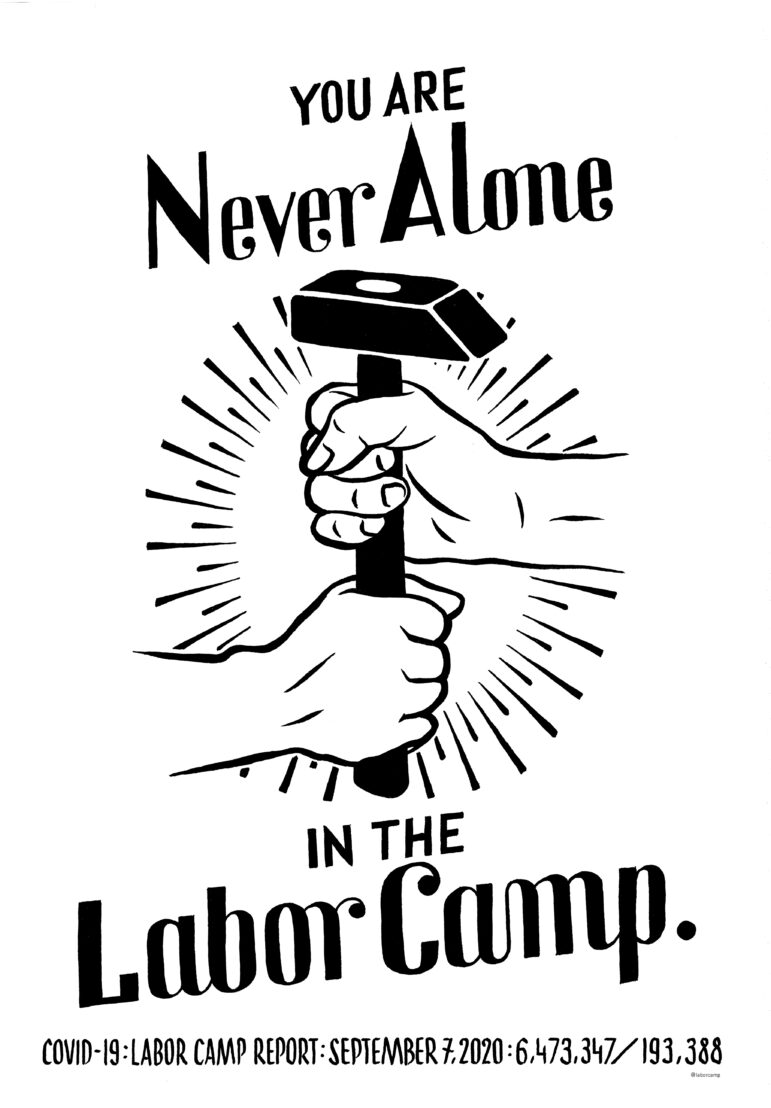

Though there is a solemn tone to the poster series, it is not without its sarcastic humor. One poster from September 7, 2020 reads, “You are never alone in the Labor Camp.” with two hands gripping a hammer. Through mass death and isolation, the hands evoke shared misery, but also a persistent hope through solidarity and unity.

Repositioning propaganda

Szyhalski examines the themes of political and state violence, and economic coercion long before the pandemic, and in many ways his lifelong interest in these themes set him up well to create 225 posters. His lifetime of work also consistently examines the use of ephemera and propaganda, from posters to leaflets to banners. In a piece that sits at the corner of the gallery, a machine spits out the leaflets up in the air, causing hundreds to amass on the gallery floor. The guests can pick them up, take them home, step on them, or display them elsewhere if desired.

The leaflets feature jarring phrases and imagery, including a diptych of camo print above the text “If” beside an image of a rash on a person’s skin with the text “Then.” On the flip side of the leaflet, an image of the American flag with the text, “You decide.” The artist then repeats this structure of “If” and “Then” with different imagery, critiquing the devastating cost of war on human beings.

This is only intensified upon learning more about the historical context of the leaflets. During the U.S. invasion of Iraq, American warplanes littered hundreds of thousands of leaflets above no-fly zones, threatening Iraqi people not to defend themselves or aggress the American planes hovering above. The leaflets dropped by the U.S. military read, “Before you engage coalition aircraft, think about the consequences.” “Think about your family, do what you must to survive.” “No tracking or firing on these aircraft will be tolerated. You could be next,” evoking a similar semantic structure to Szyhalski’s reappropriation.

Szyhalski’s intensive study of propaganda serves as a starting point to create his own subversive interpretations. By reappropriating American war propaganda and contextualizing the ephemera within its violent and imperialist history, the leaflets arouse an even more chilling and disturbing reaction in the viewer. The artist explains, “Material carries a lot of weight, even before there’s any content present. The material itself already suggests, and brings a certain set of considerations, history, implications, ideas in and of itself.”

The artist approaches and reapproaches the same ideas through different sensory experiences, mediums, scales, and environments—creating an all-encompassing thesis that undeniably is pro-worker and anti-war alike. In the face of mass loss from war, disease, a poisoned environment, and working people to death and despair, the work of the artist is to persist through.

Material carries a lot of weight, even before there’s any content present. The material itself already suggests, and brings a certain set of considerations, history, implications, ideas in and of itself.

– Piotr Szyhalski

Performance as protest, protest as performance

In another corner of the exhibition, there is a small screen playing a loop of various performances consisting mostly of experimental sound design for live audiences in galleries, along with protest imagery and a video of a 2017 performance taking place at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, where the artist works as a professor. Szyhalski and a group of students unveiled a massive banner with the straightforward message: “Their wealth, your misery…Your illness is their income,” along the campus main thoroughfare. It reads as both protest and performance art, and implies a potent overlap between the two. The unveiling of a banner can serve as a centerpiece to a picket line and a fine art exhibition alike.

Some organizers may balk at the idea of protest as a performance, and propaganda in general—certainly the terms are frequently weaponized as a critique of activism that prioritizes clout, clicks, and imagery. However, performance and propaganda are not inherently frivolous or demonstrative, but rather, have a vital role in social and political movements.

Art and performance have long been tactics in protests, social movements and strikes. Through the ‘80s and ‘90s, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) staged die-ins on the steps of the Food and Drug Administration building to bring attention and a sense of urgency to the mass death and illness in gay and trans communities while politicians chose to ignore the crisis. In a 2019 demonstrations led by photographer Nan Goldin, protesters released hundreds of flyers that read, “Sacklers lie, people die” and distributed fake prescriptions in the lobby of the Guggenheim to protest the the Sackler family’s role in the opioid crisis, as well as the museum’s financial relationship to the family. More recently, unionized Starbucks workers in Chicago constructed large puppets on the picket line and reappropriated the company’s own holiday marketing campaign for the purposes of the day-long strike. In this compelling intersection of propaganda, protest, and performance, Szyhalski finds himself in a continuum of a long history and amongst righteous company.

The exhibition opening of the initial iteration of the banner piece, titled THEM (at the now closed Soap Factory gallery in Minneapolis) coincided with the police murder of Jamar Clark, whose killing sparked weeks-long occupation of the Fourth Precinct in north Minneapolis. When Szyhalski first heard the news of the 24 year-old’s death, the artist had an idea: He had all the equipment in place, and offered his tools and know-how to organizers to create their own banners for the demonstrations with whatever language they chose. In images of the protests, the banners can be seen in Szyhalski’s signature style reading “Justice for Jamar!” and “End State Violence!” Thus began Szyhalski involvement in on-the-ground protest movements for several other local protest movements in the years to come.

A collective approach to art

Szyhalski explains to Workday Magazine how this shift in his practice then opened up questions of traditional notions of authorship in his work. Not only would he allow the organizers to decide the text, he also began to invite them and their families into his studio to produce the enormous banners alongside him, creating an intimate moment of shared creation and connection. Szyhalski described these collaborations as a “moment of ownership, authorship shifting, away from me and becoming more of a kind of a collective.”

This more democratic approach to art is not only seen through the shift in authorship, but also in how the artist leaves copies of the posters in a box in the gallery for viewers to take for free. During a time when so much art is monetized and kept away from the public, Szyhalski’s impulse to reach the masses with his messages is unfortunately rare in fine-art settings, and all the more refreshing. Instead of maintaining the notion of scarcity as a means to signal value and elitism, the artist insists on delivering his work to the public sphere. Had my coworker not brought a poster back to the office, I possibly would not have had this encounter in the first place.

This collectivist approach to authorship, along with the public viewership that is inherent to the medium of posters and banners, allows for significantly more flux in the meaning to the work—and, as Szyhalski notes, the work “continues to mutate its own form.” As time goes on, as different crises wax and wane and compound, as terror, war, and disease rage on, his work will continue to dissect and detangle the moment, while shapeshifting itself in the process.