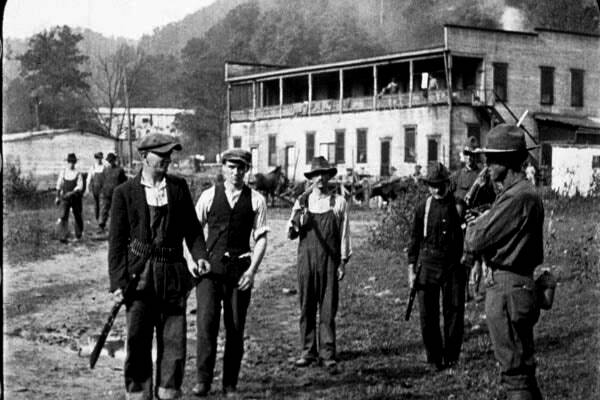

KENNETH KING, WEST VIRGINIA MINE WARS MUSEUM

KENNETH KING, WEST VIRGINIA MINE WARS MUSEUM

Share

One hundred years ago this month, thousands of coal miners — along with hundreds of farmers, merchants and ministers — rallied south of Charleston, West Virginia, before marching southwest toward Mingo County to unionize its coal mines.

Their hero was Sid Hatfield, police chief of the town of Matewan in Mingo County. On a drizzly day in May 1920, Hatfield and some of his friends had gone toe-to-toe with security agents hired by the coal companies to evict miners from company housing. An ensuing gunfight left seven of the detectives dead on the main street of Matewan. A year later, Hatfield was murdered by coal-company security agents at a neighboring courthouse. As he climbed the steps, unarmed, they gunned him down. Hatfield’s murder set off the “March to Mingo,” the largest armed labor uprising in American history.

The miners experienced something that many of us learned from the Covid-19 pandemic. They were effectively essential workers, like those today who have risked their lives to keep hospitals and grocery stores functioning. No other peacetime occupation called upon men to subject themselves to the dangers mining entailed — the constant possibility of death from poisonous gasses, explosions and roof collapses that could entomb them deep in the earth. Yet no occupation was so central to the industrial power of the United States. And while we progressives now call on the United States to eliminate fossil fuels of every kind and shut down every coal mine to stave off the worst effects of climate change, we should recognize miners as brave and maligned workers who deserve retraining for new occupations — and financial security.

Since 1890, miners had been organizing locals of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), often at great risk. Politicians, managers, and the police all panicked at the idea of a multi-racial union made up of southern whites, European immigrants and African Americans. In violation of the state constitution, the political leadership of West Virginia allowed mining companies to brutally crush any effort by miners to unionize.

For decades, miners had endured beatings and murder by coal-company guards and hired agents. For decades they had attempted to improve their pay and safety through negotiation and strikes — with essentially nothing to show for it. The companies ignored the appalling rate of underground fatalities. “Kill a mule, buy another,” went a miners’ saying, “kill a man, hire another.” A dead miner’s family would be evicted from their company house so that it could be rented to the family of his replacement. Pushed to extremes, and seeing no other way to be heard, they met violence with violence. Nearly 60 years after the Civil War, thousands of Americans were about to fight for their right to unionize — and for the dignity of labor.

And fight they did. Along their path to Mingo County lay Logan County, the fiefdom of anti-union sheriff Don Chafin. Coal companies bribed Chafin and financed his department to suppress unions by any means necessary. To stop the march, he recruited over 1,000 volunteers, many of them deputies, and equipped them with machine guns and high-powered rifles, billing the coal companies. His force took up strong positions along the top of Blair Mountain, a ridge inside the eastern border of Logan County.

For nearly a week, the miners tried to break through. General William “Billy” Mitchell, founder of the modern United States Air Force, ordered in four planes capable of dropping bombs on the miners, as well as 17 fighters fitted with machine guns. During the battle, up to 100 men were killed and many hundreds more wounded, mostly on the miners’ side. President Warren Harding sent in infantry troops to stop the miners, many of whom had fought in World War I and hoped the soldiers would support them. But they were wrong.

Almost 1,000 marchers were charged with state felonies and some served up to four years in prison, though many were later pardoned. The UMWA almost went bankrupt defending the charged miners in court. These demoralizing losses caused membership in the UMWA to plummet in southern West Virginia. The coal companies ruled while working and living conditions deteriorated. Miners didn’t feel safe from company harassment and violence until President Franklin D. Roosevelt initiated the New Deal in 1933 and signed the Wagner Act in 1935, which guaranteed the right of workers to form unions and established the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB).

During the 40 years after 1933, widespread unionization brought economic prosperity, proving that when working-class Americans have stable homes, functioning communities and access to education, all of us thrive. But since the 1970s, corporations have found ways to undermine the right to unionize — by forcing workers to attend anti-union meetings and watch anti-union propaganda, by threatening termination of those who attempt to organize, and by making it known that there is no such thing as a secret ballot.

Earlier this year, the NLRB found that Amazon had intimidated workers engaged in a unionization vote by installing a mailbox and security cameras outside its fulfillment center in Bessemer, Alabama. The company signaled to its workers that it was watching them. Yet while rates of unionization are lower than ever before in American history, 65 percent of Americans support the labor movement. The 2018 wildcat teachers strike in West Virginia demonstrated the power of public-sector workers to shame legislators and win concessions. Nurses are organizing all over the country in response to low pay and the indifference of hospital administrators to their well being during the pandemic.

This is how we should remember the Battle of Blair Mountain and the miners who fought there. Collective bargaining and the protection of the government from the greed and exploitation of capitalism was all they wanted. To honor them, today’s labor leaders shouldn’t take up arms, but should use every other tool they have to secure workplace democracy, a living wage and the dignity of labor.

This story was originally published by In These Times