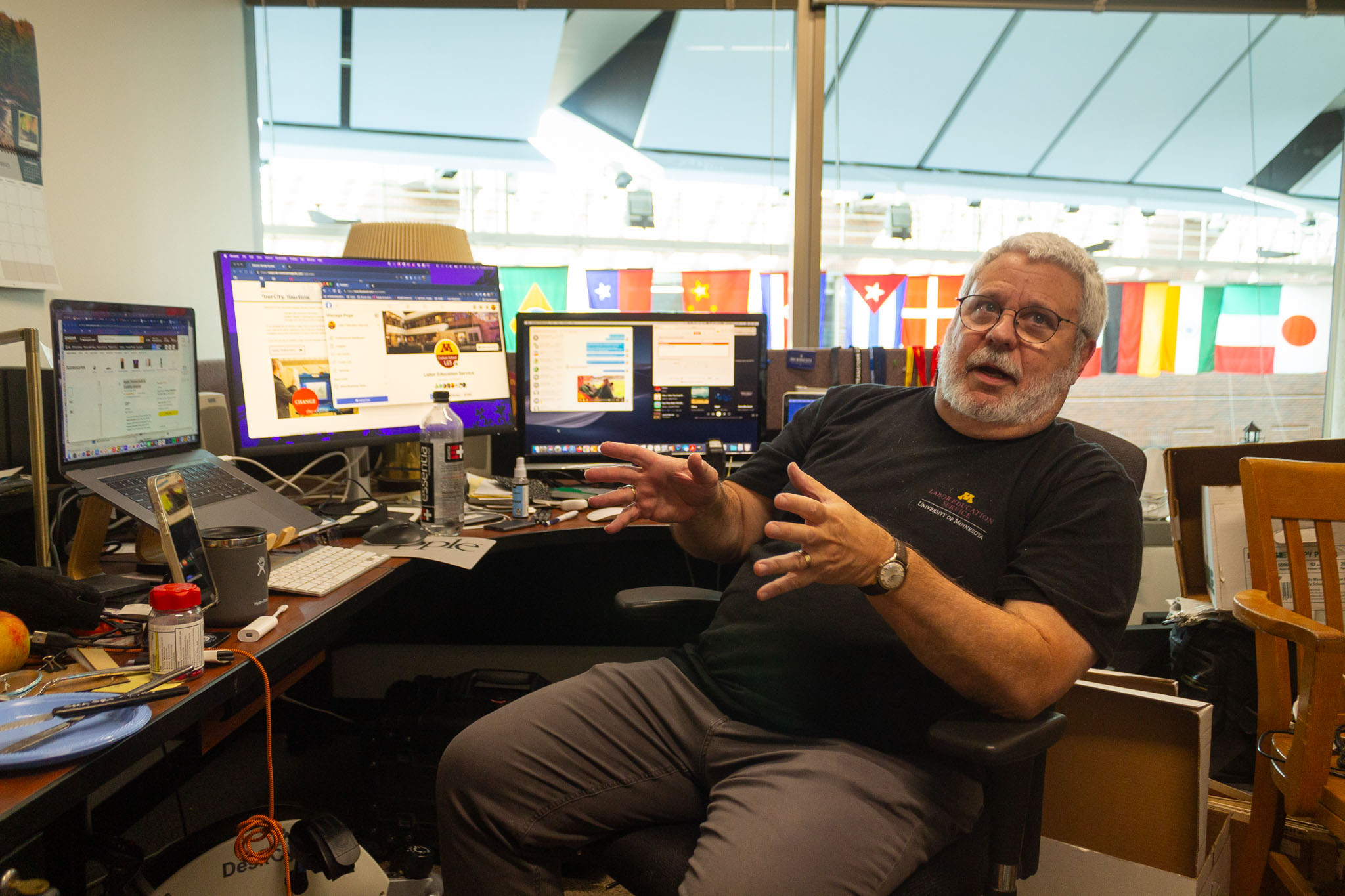

John See in his office at the University of Minnesota. Photo: Isabela Escalona.

Share

In October 2023, John See worked his last day at the Labor Education Service (LES) after a 39 year tenure. His office was a treasure trove of Minnesota union history—adorned with vintage Teamsters trucker hats, retro pins from the 70s, and a constant stack of VHS tapes digitizing onto one of the half dozen monitors where he was often seen fervently editing videos and coordinating audio visual work for major conventions. While See’s office may be cleared from the nearly four decades of ephemera, his legacy and dedication to Minnesota’s labor movement continues.

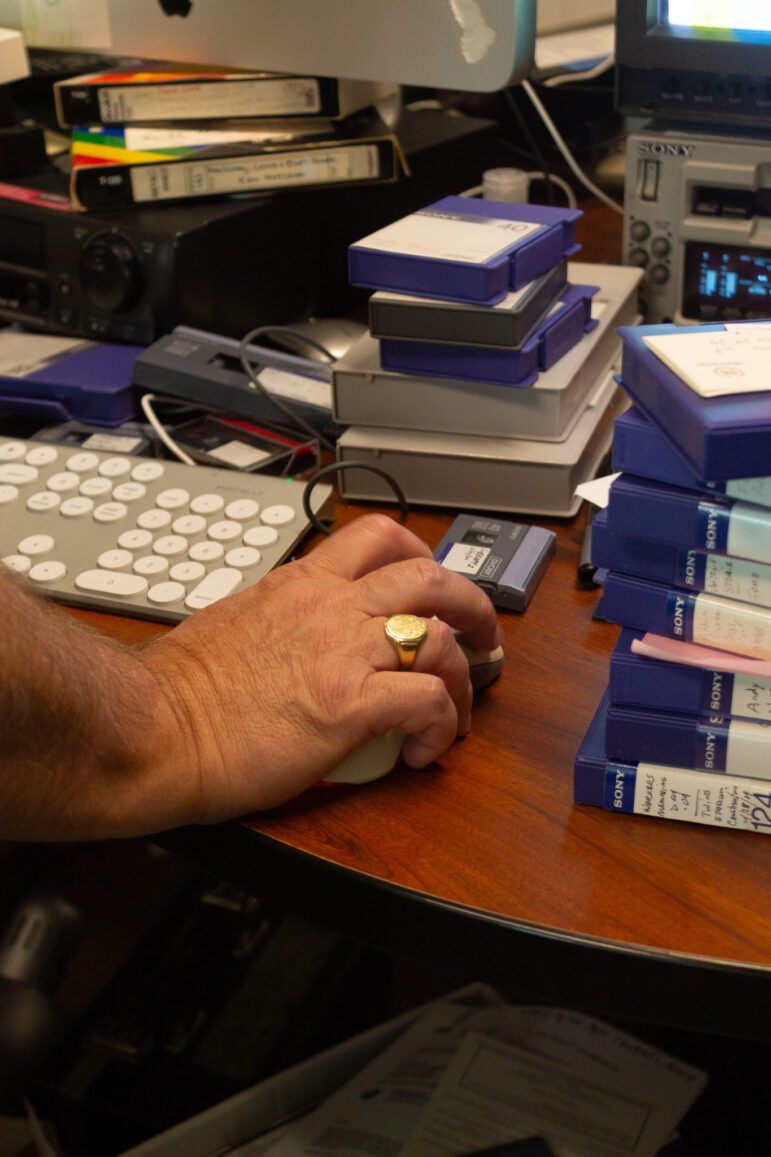

See concluded his career with a massive, archival project. He digitized thousands of tapes of the public access program, Minnesota at Work, which aired from 1984 into the early 2000s, featuring workers speaking about their lives and working conditions, working with Randy Croce, Howard Kling, and the late Martin Duffy. Along with Minnesota at Work, many different kinds of programs have been archived. These videos begin in 1977, including from historic strikes, union events, grand openings, galas, iconic Minnesota politicians including Hubert Humphrey, Nellie Stone Johnson, and Paul Wellstone, conventions and all things Minnesota labor history.

In the coming year, the archival project will be available to all through the University of Minnesota’s Library digitization service titled Elevator, where labor leaders, historians, students, teachers, journalists, professors, and anyone else who may be interested can take a deep dive into the roots of the Minnesota labor movement, for free.

Workday Magazine interviewed John See shortly before his retirement about the changes he’s seen over the past four decades in the Minnesota labor movement, in both media and technology, and his advice to those who wish to continue this legacy of democratizing media and technology and devotion to the working-class struggle at the intersection of media and history. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Workday Magazine: Where did you grow up and what was your early life like?

See: I was born in Hartford, Conn. in 1958. My family moved to Cambridge, Mass., for my first couple of years. And then we went to the Virgin Islands, where my dad was a missionary in an Episcopal parish there. For six-year old me and my younger siblings, it was fabulous because it was outside, classes were in cinder block rooms with louvered windows. The weather was mostly nice and there was a beach nearby. It wasn’t fancy but it was idyllic.

We moved back and went to Barrington, R.I. where I spent the next years through high school. The culture shock was very interesting, because to come back from the Virgin Islands to a brick and mortar school in a northeastern town was a complete shock. Our grandparents brought blankets in the car at the airport in Boston. Everything was different. The recess time was different. The kids were different. But we acclimated and settled in for the next several years.

Workday Magazine: How did you end up in Minnesota?

See: I went to speak with a dean at Brown University who had just been in Minneapolis. She encouraged me to apply to the University of Minnesota. I applied and got in, came out here in 1977 with a duffel bag and a guitar.

When I first got out here I was like, “Holy moly, this is really big and spacious, not at all like R.I.” I decided after a while to go into speech communications broadcasting with a minor in theater. So I did a lot of acting, was a teaching assistant in the edit lab in Rarig Center, and I also did speech communications research. Fortunately, I had a couple of brilliant advisors.

Workday Magazine: What was your work experience before you started at the Labor Education Service?

See: I got a job right out of college. I got a job at a public access facility in Fridley, my first union job. And then, later Eden Prairie in the playback center making sure the right shows were on at the right times. During that time, you’d go into the edit bay, and you’d do the commercial inserts. This didn’t happen by magic. You would get a commercial from a local company, put four of them together, you edit them together and kick them out as a package, and then they have to be put in to play in the commercial breaks. They take a tone from a satellite, trigger it, and then they would play. I didn’t want to do that wrong because the sponsors would get very upset. Plus, because it was a public access facility, I had access to the studio and equipment and I used that access constantly.

Workday Magazine: What did you use the studio for?

See: The first one was The Mary Hanson Show. Mary Hanson is still on the air. It’s the longest running public access show in the country. I learned a technique where you ask a very simple, even naive question—and wait. Because the answer you get is going to be exactly what you’re looking for. The person you’re interviewing may think you’re a little ill informed and you can play that game. So I learned a little bit about interviewing that way, and how to listen. I also learned a lot about directing, camera-operating, and editing, so it was this ideal environment.

Workday Magazine: How did you begin working for the Labor Education Service?

See: I answered an ad in the paper. It was the Minneapolis Tribune, now the Star Tribune. I still have that in my files. It asked for people who knew about video and public access in particular.

Workday Magazine: What were your job duties when you first started?

See: The goal of the program was to be able to tell workers stories using the medium of public access, because it gave everybody equal access to technology that you couldn’t afford before, which was excluding a lot of people. We tried to do four shows every month. I started the series Minnesota at Work in 1984. It was sponsored by the Labor Education Service and the Minnesota AFL-CIO, who were major supporters.

It’s important to note that when the tapes went to the public access station, they had to be driven. So you’d make the tapes, and then you drive them out to the various stations, and they’d plug them in. Eventually, you’d go back with the next batch and get that batch back of tapes. It was a brutal schedule.

People were asking, first of all, why is the Labor Education Service in the television business? Eventually, they saw what was going on. It was essential that I was a union member. First I was with MFT 59, then a full member-at-large of IATSE 219. We made programs called What Unions Do where we went out and interviewed four very different union people. We did a 20-minute show. This whole thing came together in this really neat program. Professionally done. We showed it in union halls and on access. A lot of people saw it.

Workday Magazine: What was the mood, the general kind of tone of the labor movement in those days?

See: Reagan was in office and Reagan was decimating working people and the labor movement in general. He took out the air traffic controllers, which some people are only perhaps now realizing how incredibly important that was. It cut unions off at the knees and set the tone. And that was the tone, 1980s and onward—that businesses could do anything they wanted to unions, and they had free rein.

When I came in, it was that you could have a business program on PBS (now TPT) Channel 2. But you didn’t have a labor program at Channel 2, because labor was a special interest. They told us, “You guys are a special interest. We’re not going to put your shows on.”

Workers were on the defensive. They had no presence really in the media except for strikes and strife. If you walked up West Seventh in St. Paul, you’d see stores boarded up, where you’d see apartment buildings not being used. Townhouses not being used. The situation around the Iron Range was dismal. It’s like people were just hurting everywhere. It was depressing. It was harsh.

When I went into a union hall for the first time with a camera, you gotta understand it’s a union hall, it was a meeting, it was full. And those meetings were shrinking in those days. Because everybody was getting slashed, and the unions didn’t have a whole lot of power. And then I went in to set up to film a speech and a guy looked at me and said, “What are you expecting, trouble?” That in a nutshell, that was the feeling. Cameras show up when there’s trouble, when there’s a strike. And that just wasn’t gonna change for a long time.

In that period after, I would say 1992 or 1993, we decided to bring more staff to do the same kind of work. That’s when Randy Croce and Howard Kling were hired and the Telecommunications Project really expanded. The LES staff was coming up with ideas. Unions were calling with ideas. And then I said, within this environment, I want to start teaching people how to do this. So I started teaching classes at the Minneapolis Television Network (MTN). Later, they had computer labs, so I went to MTN and offered a class in a classroom full of editing equipment. We covered everything from how to use the computers to coding web pages in HTML. We did the same at the former Earle Brown Center on the University’s St.Paul campus.

Workday Magazine: You mentioned unions being skeptical, and maybe people in general were skeptical of video at the time. How did you gain people’s trust with using a camera, bringing in cameras into union halls?

See: Repetition. You showed up. You showed up at everything. You showed up at a rally, you showed up at a meeting. I mean, literally, you just were there. So people got to know your face. Then you put something out that looks good. You’re showing that you’re not screwing around with them.

You go, you show up, and then you deliver and you don’t pull any punches. And then people will call you and say, “Well, you did that for them. Can you do it for us?” So as the old saying goes, half the battle is showing up, and that’s what it was.

Workday Magazine: How do you feel the labor movement has changed over your tenure? You said it was on the defensive in the ‘80s. Would you say it’s changed?

See: It went in waves. Ronald Reagan really hammered the labor movement, the union movement. We lost a lot of members and that membership loss never came back. It kept going down no matter who was in office. You can see the numbers go down to 21% to 15%, to whatever it is now, about 10%.

I don’t think people hated unions, ever. They just got into that mindset of “Well, if they can have this, so why can’t I have that?” Instead of, “I want to be part of a union.”

The other thing is that, frankly, at that time, to put it in historical context, people who were 40 years old had come up with all the benefits that their parents had fought for in their struggles for unionism. And they were taking it for granted. “My parents had it so I’m going to have it. And now that I have it, I’m not going to pay attention to it.” And that did not help at all.

Workday Magazine: How has the media changed, especially in terms of accessibility?

See: It’s very frustrating to have had really quality programming and not be able to show it on a basis like there was a business show. Just why is business not a “special interest”? And it made us working people feel like we were less.

It changed to an extent when people found out they could use public access to make their own programming. And they really took off in many communities.

That changed on a local level for us, because now we had direct access to making programs that could go on union halls and on the channels. And then there’s all kinds of things we did in the community and we knew they were watching. But it didn’t get us on any of the major channels unless there was trouble.

Workday Magazine: Can you tell me more about the early days of the internet, how you first learned of it, and then kind of moving into how you introduced it to the labor movement?

See: The web was born in 1993. The internet was born before that. And explaining to people where it came from was always interesting, because it was a Defense Department initiative. In case of nuclear war, they set up wires all around the country that would provide redundant communication systems.

So I found out there was a new thing called GopherNet that the University of Minnesota was using to do file storage. It was the first web stuff that people would save things and they put them in folders. I was recovering from a spinal fusion surgery and had the time on my hands to research this thing called the web.

The big issue was access for years. We would go to unions and say, “Look, we’re doing this thing called the internet. We have these pages we’re putting together with information on them.” But they’d say “Our people can’t get on, because you needed a phone line and a computer and they can’t afford computers.” So we tried to do things like encourage members to talk to their union presidents and say, “Why don’t you put three computers in your union hall?” Let the members come in, access the internet, and encourage them to get them back to the union meetings. And some of them did get to it.

Workday Magazine: That’s really cool, because you had this interest in technology but it was always coupled with access and how working people will use it. And I think you were that really important link in the labor movement, especially seeing its potential and actually showing it to people.

See: That was our underlying drive, we got to get the word out. And there’s no other better way to get the word out. At the time, computers and internet access was community-supported, everybody supporting each other, and it was very communal. It was very much the open commons. It’s really a fascinating time because we were learning how to use this tool but didn’t know how unions would be able to use it yet. There’s a good academic thesis in there for someone.

Workday Magazine: What was your favorite piece of media that you ever made? or projects that you’re a part of?

See: The video we did with Mike Jwanouskos. We got to work with the Teamsters on this one. Mike’s dad was a trucker so he had health insurance. Mike was born with cerebral palsy and he shot the bow and arrow, but he had to shoot with his teeth. So we heard about this kid that shot archery with his teeth and he was a Teamster’s son. It was a great story.

He was going to go to the Olympics and the Paralympics in South Korea. So we went over to meet Mike and his parents and we worked with the Teamsters on this. We followed him to Las Vegas and recorded him. This kid was amazing.

So we recorded all of this plus the family backstory. The video was used, he used it everywhere, he went to talk about what you can do with a disability. He did talks at schools with our program.

Shoot ahead 20 or so years later, I got a call from Mike. Now he only has use of one arm and he eventually had to stop shooting bow and arrow because he couldn’t do it anymore physically. So he started target shooting and was very good at that. When we hooked back up again, years later, he was a grown man working at the MInnesota Department of Labor and Industry. To me, he’s always a 16-year-old kid, you know, but that project had this lasting effect.

Workday Magazine: That’s such a unique labor story, because it’s not your typical thing you would expect of a labor story. But that was all possible from his dad’s healthcare and pension benefits plan.

See: The Teamsters Joint Council 32 were supporters of our Telecommunications Project and they underwrote this show. We went all over the Twin Cities to capture Mike’s practices and competitions. Eventually we followed him to Olympic qualifiers in Las Vegas. We produced a 28 minute in-depth story.

Without our program he would have gotten a 32-second segment about the kid who shoots the bow and arrow with his teeth and they wouldn’t have known anything else—they wouldn’t have mentioned his dad was a trucker or that this was possible because he was a Teamsters. And that’s the kind of thing that we got to do with our videos.

Workday Magazine: What is the most valuable lesson you’ve learned over the years?

See: Show up. What’s the saying? I think it’s Mark Twain’s saying, or maybe he quoted somebody else. It’s better to keep your mouth shut and be thought of as a fool than to open your mouth and remove all doubt. You just be quiet. Listen. And don’t mess with people’s trust. Don’t. No matter what happens, period. That’s my way of doing things.

Workday Magazine: What was kind of your favorite part of the job day to day?

See: My favorite part was being in the field. I’m also proud of being part of the internet coming into the labor movement here. That was incredibly important to me, the way it happened, being in a position to make this technology accessible in the labor movement. I’m very proud of that transition.

Workday Magazine: Can you tell me more about the video archival project you’re working on?

See: We digitized over 400 of our programs, mostly finished programs, plus other bits and pieces. The programs are union activities, strikes, meetings, the Minnesota at Work programs, talk shows, field shows in Minnesota, and around the country.

They’ve been digitized, and the University of Minnesota library has agreed to put the programs on their server, that’s called Elevator where they will be searchable by keyword. So if you know your union did something, you could search for “SEIU” or “CTUL.” You’ll be able to search names of people, what year. This makes it so it doesn’t sit on the shelf. The earliest footage is probably around 1977.

Workday Magazine: Can you tell me who this archive really will be most beneficial? Who would be interested in this type of material?

See: First of all, researchers for sure. Academics, high school teachers looking for information for History Day. There are some primary sources here that they could pull. We’re not charging for it. This is all free.

Kids can look things up for their projects, teachers can look things up for history. There’ll be union members who may want to point back to a historic strike. So there’s history for the general public. And workers and then certainly unions, union members who might want to know about this stuff.

Workday Magazine: Can you tell me more about the television program, Minnesota at Work?

See: Minnesota at Work started as Minnesota Labor ‘84. That was the first title. Then it became Minnesota Labor ‘85 and Minnesota Labor ‘86. It looked like it was going to go on for a while and we needed to make a branding change. So we turned it into Minnesota at Work around 1987 and it continued up until 2008. It was interviews with workers. It was a cable show that ran every week.

It included interviews with workers, a talk show, legislative wrap-ups, addressing the issues that have just happened in the legislature. It was talking to union leaders and rank and file on a picket line. It was going and talking to people about what they wanted to see in the labor movement. It was people who won community service awards. It was really important stuff around the state that nobody would have known about. We worked with many, many great people. The support we received from the labor movement was extraordinary.

When we moved the show to the internet, we turned it into a magazine style format. Well, we went with what other people were doing. So if you see some of those shows, where I’m probably hosting. They were about 20-minute segments. And eventually that would become a part of the formation of Workday Minnesota, the first online labor magazine in the country, established in 2001 and edited by Barb Kucera from the Union Advocate newspaper. Workday Minnesota then shifted into Workday Magazine in 2022.

Workday Magazine: And we talked a lot about repetition and showing up and following through, but the union card is also a key to success in this work.

See: It’s been a really interesting ride. I’ve been fortunate to see a lot of things change. A lot of things changed that I didn’t expect in this job. And it’s important to note that, like I said, pension, vacation, healthcare. I had that. How many people have one job anymore in their lives? Don’t take it for granted.