Share

Chances are, you’ve got some in your cupboard: Ritz Crackers, Wheat Thins, Oreos, Chips Ahoy. And now there’s a very high chance that the crackers and cookies you are eating were made in Mexico – putting hundreds of Americans out of work.

The iconic Oreo, around since 1912, was produced at a Chicago bakery – once the world’s largest – for more than half a century.

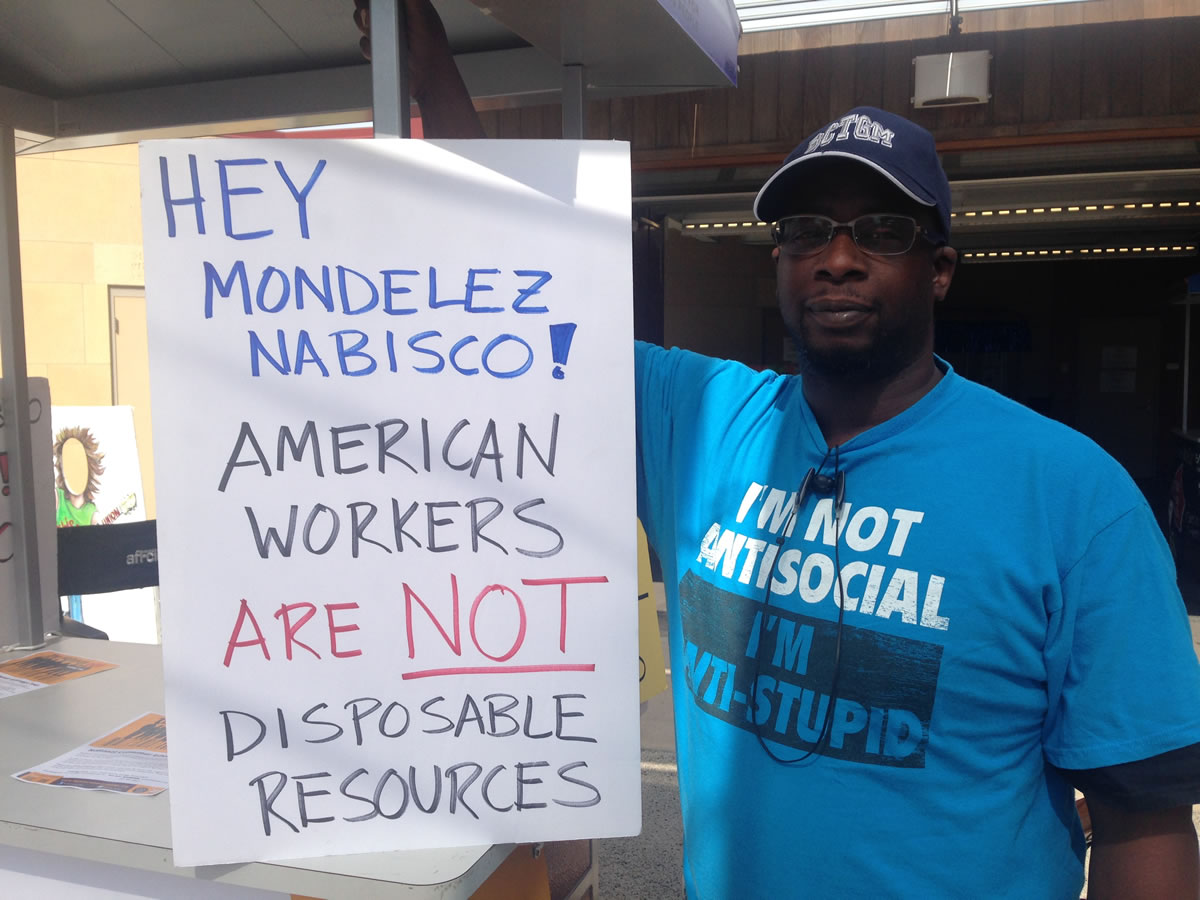

Anthony Jackson, a Navy veteran and father of three, worked at the plant for five years in a variety of jobs, mostly recently mixing icing for Oreos. But this spring, he and hundreds of other workers were laid off when the owner of the Nabisco brand – Mondelez International – moved production to Mexico in search of greater profits.

“There are families working there that go back five generations at the plant,” said Jackson. “It is the biggest employer in the area. If people get laid off, where are they going to go?”

Jackson brought his story – and call for a boycott of Nabisco products – to the Minnesota AFL-CIO pavilion at the Minnesota State Fair. His visit was part of “The Nabisco 600 National Tour” of workers traveling across the United States to fight back against the loss of American jobs.

In July 2015, Nabisco announced it had chosen to invest an additional $130 million in its new $400 million plant in Salinas, Mexico, instead of investing that money in its plant in Chicago. It did so after workers in Chicago, represented by the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco & Grain Millers union, refused to accept permanent pay and benefit cuts of 60 percent.

Layoffs began in March, with production shut down on Oreos, Ritz Crackers, Honey Graham Crackers, Chips Ahoy and Wheat Thins. Some production lines at the plant continue to make Premium Saltines, Cheese Nips and Animal Crackers, among other snacks, but workers worry those operations will be closed, too.

The facility is located in “a very diverse neighborhood” of southwest Chicago, Jackson said. Seventy percent of the plant’s 600-member workforce is African-American or Latino, but there is a large contingent from the city’s Polish community and many workers who are age 40 or older.

“There are many people there who are not going to get another job,” he said.

Jackson earned a good wage – $26 an hour plus benefits – before being laid off.

“We’re hearing [workers] are making $60 a week with little or no benefits” in Salinas, Mexico, he said. The union has filed a complaint that the move violated provisions of NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement.

Nabisco is part of Mondelez International, leading many people to naturally assume the company is part of a foreign-based multinational. But Mondelez was formed in 2012, when the food giant Kraft – under pressure from investors – spun off its global snack-food business and gave it a new name: Mondelez International. It retained its cheese products in a small company named Kraft Foods Group.

Mondelez is now the second-largest confectionery company in the world and is headquartered in Deerfield, Ill.

The company already had closed several U.S. plants before the spin-off, but pressure to cut labor costs and squeeze out more profits continues.

Jackson and other Nabisco workers are urging consumers to visit www.fightforamericanjobs.org, sign a petition of support and learn how to identify where their snacks are made. They are asking people to call on their local groceries to stock only Nabisco snacks made at U.S. plants.

The only Oreos still produced in the United States – a fraction of those sold in this country – are made in Atlanta, Jackson said. In 2015, Mondelez made $2.9 billion in revenue on the sale of Oreos alone.

In May, Jackson was among a handful of Nabisco workers who attended the Mondelez shareholder meeting, where he asked CEO Irene Rosenfeld why she was entitled to $170 million in compensation over the last eight years while putting people out of work.

Rosenfeld, he said, replied that the workers received “fair market value” for their labor.

That irks Jackson – and motivates him to keep taking the Nabisco 600 message across the country. “We’ve had a lot of great support,” he said.

“We are dealing with a large corporation,” Jackson said. However, “for every corporation, there are a billion of us.”