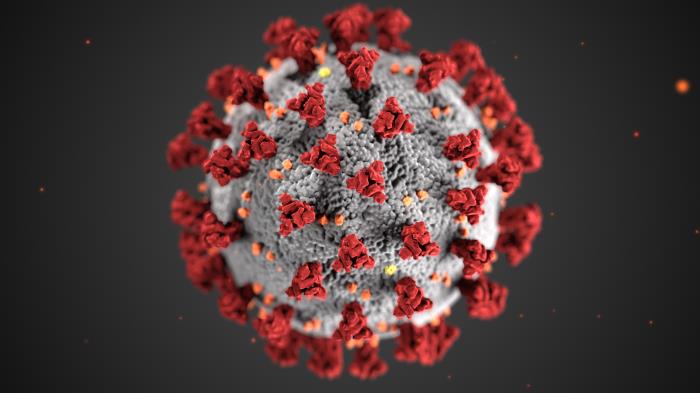

This illustration, created at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), reveals ultrastructural morphology exhibited by coronaviruses. Note the spikes that adorn the outer surface of the virus, which impart the look of a corona surrounding the virion, when viewed electron microscopically. A novel coronavirus, named Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was identified as the cause of an outbreak of respiratory illness first detected in Wuhan, China in 2019. The illness caused by this virus has been named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Share

Jigme Ugen is president of the Minnesota Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance. He wrote this column for the May 2020 issue of the Saint Paul Union Advocate.

Over 2 million Asian American Pacific Islanders (AAPI) work in healthcare, transportation and service industries. The alarming influx of racism, bigotry and xenophobia against members of this community has been a tremendous burden as they try to work through a global pandemic, often without proper personal protective equipment, or keep their small businesses afloat.

There have been countless incidents of micro-aggression, boycotts, bullying and hate crimes across the country. Take the stabbing of a Burmese father and two sons, ages 2 and 6, at a Sam’s Club in Texas; or the acid attack on an Asian woman in Brooklyn; or the racist note taped on the door of a Hmong family in Woodbury. The FBI warns of a potential surge.

Chinese immigrant workers can be traced back to the California Gold Rush in the 1840s and, later, in the mining and railroad industries. They were seen as taking other people’s jobs away and working for less.

On May 6, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act into law, placing a 10-year moratorium on all Chinese migration. It is considered one of the most toxic and disgraceful anti-immigration measures in U.S. history. The measure was supposedly repealed in 1892 but continued to be enforced until 1943. One of the driving forces behind the passage of this law was the Knights of Labor.

During the 1980s, when severe oil and gas shortages threw the U.S. manufacturing sector into crisis, politicians, corporations and organized labor used the Japanese auto industry as a scapegoat. Everyone who looked Asian became targets of hate crime, and people who drove Japanese cars became targets of scorn, sometimes even shot at. In 1982, 27-year-old Vincent Chin, a Chinese American who was celebrating his bachelor party in Detroit, was bludgeoned to death by two white autoworkers. The perpetrators were heard shouting, “It’s because of you m@f#rs that we’re out of work!” Chin’s killers never spent a full day in jail and were fined just $3,000.

From the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II to vicious attacks on Muslims and Sikhs after 9/11, from Wisconsin’s “Save a Hunter, Shoot a Hmong” slurs to the detention and deportation of Southeast Asian immigrants and refugees, racist resentment against APIs is a recurring pattern in American history.

History also shows that poor and working-class immigrants and communities of color are often scapegoated during public health crises or in wartime. When an anti-immigrant, racist administration, having proven incompetent in dealing with the outbreak, calls COVID-19 the “Chinese Virus” – with full understanding of the negative impacts it will have on every person of Asian origin – it is not a new narrative. It is an effort to distract, deflect blame, divide the country and spark fear among their followers. It’s an attempt, once again, to turn this nation’s people against another race of people. For a majority of Americans, every Asian is Chinese just like every brown person is a Muslim and every Latinx is Mexican.

Racism against Asian-Americans is real, and it is dangerous. COVID-19 is not the only invisible enemy we face during this pandemic. If you see a co-worker being harassed or hear racist jokes, always be an ally. Intervene and speak up, because people’s behaviors will not change if they do not believe a problem exists or sense a real reason to change. Let the labor movement’s tradition – “an injury to one is an injury to all” – be applicable for everything.

Many national labor unions, civil rights and racial justice organizations have issued calls to action denouncing the discrimination against AAPI, and the Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus drafted a letter urging public officials to help prevent the spread of misinformation. As local unions, we should sign-onto these letters, provide similar statements and pass resolutions denouncing racism towards AAPI. And most importantly, we should share them with our members.

Now is also a good time to check on your AAPI members, whether it’s through email, text, personal calls, etc. Listen and re-affirm that they are not alone.

We need to learn from our history to change it, and have the courage and leadership to counteract fear and anxiety. In addition, I highly encourage you to be cognizant of maintaining adequate AAPI representation in leadership positions and board seats in our unions.

This moment requires unity to collectively prevent the spread of both the coronavirus and racial stereotyping, otherwise these dangerous and dogmatic narratives will leave lasting impressions for us to fight long after the virus is defeated. This virus does not discriminate against workers based on race or immigration status, and neither should we. And when we get to the other side of this crisis, let’s be able to say that this virus brought best out of us, that we endured it together with complete solidarity and kindness, and that no worker was left behind.

– Jigme Ugen is a Tibetan refugee and the executive vice president of SEIU Healthcare Minnesota. He also serves as a board member of the Minnesota AFL-CIOand the Minneapolis Regional Labor Federation.