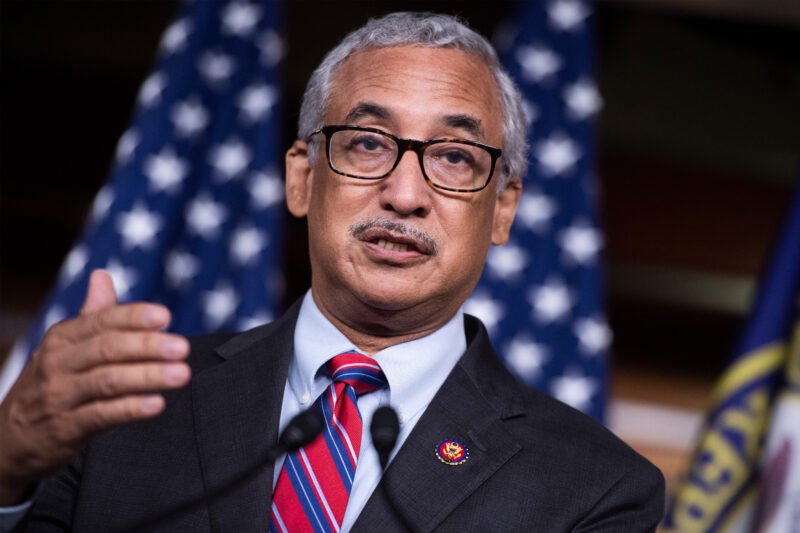

Rep. Bobby Scott, chair of the House Committee on Education and Labor, accused the National Labor Relations Board of obstructing his committee’s oversight efforts. (Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images)

Share

This story was originally published by ProPublica. ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

House Democrats are set to issue a subpoena Tuesday to compel the National Labor Relations Board to hand over documents as part of an inquiry into potential ethical lapses at the board, according to congressional aides. The move, by Democrats on the House Committee on Education and Labor, marks a significant escalation of a long-running investigation and follows the repeated refusal by the NLRB’s chairman, John Ring, to produce the documents voluntarily.

The subpoena demands that the labor board produce a set of documents linked to its efforts, under the Trump administration, to undo one of the landmark decisions of the Obama-era NLRB, which expanded worker protections by broadening what is called the “joint employer” rule. That decision left companies on the hook for labor law violations against workers not directly employed by them, like temp staff and employees of fast-food franchisees. It meant that a parent corporation like McDonald’s, one of the companies embroiled in litigation over the rule, could be held liable for a franchise owner’s wrongdoing, such as retaliating against workers for trying to unionize. That had implications for the profits of corporations that operate on a franchise model and for contract-staffing firms, like cleaning services.

House Democrats see the documents, which include ethics reviews written by NLRB lawyers, as key to addressing their concerns that the actions by the Trump-era NLRB — the agency made three separate attempts to overturn or undermine the Obama-era rule before succeeding — were tainted by conflicts of interest, as well as potential violations of federal contracting law.

In a Sept. 1 letter to Ring, Rep. Bobby Scott, D-Va., who chairs the House Committee on Education and Labor, accused the labor board of obstructing his committee’s oversight efforts and suggested that its refusal to produce certain documents indicated that the NLRB has “something to hide.” (ProPublica obtained a copy of the letter, which has not been reported previously.) “The Committee is left to conclude that the NLRB’s sole motivation for refusing to produce requested documents is to cover up misconduct,” Scott wrote.

In a statement provided by NLRB spokesman Edwin Egee, the board called the committee’s subpoena “unprecedented” and noted that the agency had allowed the committee’s staff to review some documents at its headquarters in an effort to accommodate the committee’s requests while also “protecting the Agency’s legitimate confidentiality interests.” Other documents, the statement said, were withheld to protect the board’s internal deliberative processes. The statement included a quote attributed to Ring, which said that the NLRB had been “fully cooperative,” accused the committee of seeking documents it “knows it is not entitled to” and called the subpoena “a made-up controversy solely for political theatre.”

The statement is consistent with Ring’s position in earlier negotiations with the committee. In a May 14 phone call with Scott, described in his letter, Ring refused to turn over documents sought by the committee unless a federal judge ordered him to.

As other House committees have seen firsthand in recent months, resort to the courts would likely leave the subpoena in limbo for months. This fight is likely to persist. Because NLRB board members serve fixed five-year terms, the agency’s Trump-appointed majority will remain in place until August 2021.

The NLRB has experienced periods of intense congressional oversight in the past. During Obama’s first term, for example, the Democratic-run board faced wide-ranging document requests and subpoenas from House Republicans. Although the board withheld some documents, it willingly turned over tens of thousands of pages to congressional committees, according to Wilma Liebman, who served on the NLRB across three administrations, from 1997 through 2011. “We always thought that, as excruciating and time-consuming as it was, we had an obligation to comply with requests from Congress,” Liebman said. “They’re the source of our budget, for heaven’s sake.”

The documents the board held back in the past, according to Liebman, contained records of its internal deliberations in ongoing cases — documents that, if disclosed, could confer an advantage on one party to a labor dispute. In its statement, the NLRB points to this precedent to justify refusing to turn over the documents sought by the House committee. But, Liebman said, the logic that supported withholding documents doesn’t apply to the current fight because this one centers on allegations of conflicts of interest.

The House inquiry began after the NLRB’s first attempt to roll back the Obama-era expansion of the joint-employer rule, in a 2017 decision titled Hy-Brand Industrial Contractors. A Trump appointee named William Emanuel cast the deciding vote in that case — only to have the NLRB undo that vote after its inspector general and an ethics officer concluded that Emanuel should have recused himself because of the involvement of the law firm where he had previously worked, Littler Mendelson, in the Obama-era case it overturned.

The new subpoena focuses on the unusual lengths the labor board’s Trump-appointed majority subsequently went to as it sought to get rid of the more expansive joint-employer rule. House Democrats argue those efforts raise additional ethical concerns.

Starting in 2012, workers at McDonald’s franchises claimed they were fired or otherwise retaliated against for their involvement in protests seeking union representation and higher wages as part of the “Fight for $15” campaign. The Obama-era NLRB filed complaints not only against the franchise owners but also against McDonald’s itself, as a “joint employer” of the franchisees’ workers.

But once Trump appointees took control of the NLRB, the agency went in a different direction. By the spring of 2018, the NLRB’s then-new general counsel, Peter Robb, reached a settlement viewed as favorable to McDonald’s and its franchisees. That summer, an administrative law judge rejected the settlement, noting that, among other defects, it largely sidestepped a core question — whether McDonald’s was a joint employer. McDonald’s appealed, and last December, the labor board reversed the judge’s decision and authorized the settlement, with Emanuel again casting the deciding vote in a 2-1 opinion.

Representatives of McDonald’s workers had asked Emanuel to recuse himself, citing Littler Mendelson’s legal work for McDonald’s as the fast-food behemoth sought to help franchisees fend off the protests over wages and unionization. Emanuel declined to recuse himself, on the grounds that Littler Mendelson had never represented McDonald’s before the NLRB. (A hotline the law firm set up to field questions from franchise owners remained active as of Monday.) Emanuel explained in a footnote to the majority opinion in the McDonald’s case that he sought an opinion from the labor board’s ethics officer — a document that is among those subject to the impending subpoena — but did not disclose the ethics officer’s advice.

The House committee has sought to review the ethics memorandum, in part, to determine whether Emanuel complied with its recommendations. Concerns among Democrats on the committee grew after the NLRB issued an unusual report on its recusal process last November, spurred by the earlier controversy around Hy-Brand. The report observed that a board member could “insist on participating” in a case, even when the ethics officer has determined that the member should be recused.

Ring refused to give the House committee a copy of the ethics memorandum in the McDonald’s case, but he agreed to let committee staff review it at NLRB headquarters. But Ring added a new caveat: The House staffers could only view the ethics memorandum after the McDonald’s case was completed. That has yet to happen, because representatives of the workers involved asked the board to reconsider its December ruling. In his Sept. 1 letter, Scott described that condition as an “indication that the NLRB is attempting to cover up malfeasance or misfeasance.”

The subpoena also seeks a separate set of documents. In September of 2018, the NLRB majority moved for a third time to curtail the Obama-era joint-employer rule, this time through a rulemaking process. The labor board hired a contractor to help it categorize comments submitted in response to the new rule it had proposed.

As ProPublica reported last year, contracting documents indicated the temp staff might be involved in substantively assessing the comments, which could violate federal contracting rules. The labor board, which denied that the temp staff had handled any substantive work, refused to disclose documents showing how the contractors were instructed to categorize the comments, claiming they reflected the board’s internal deliberative processes and so were shielded from disclosure.

The new subpoena seeks those documents as well as another ethics opinion provided to Emanuel. Emanuel had decided to participate in the rulemaking after the ethics opinion cleared him to do so.

A more permissive conflict-of-interest standard applies to rulemaking, and critics, including one of Emanuel’s fellow NLRB members, voiced concerns that the labor board’s resort to that process aimed to circumvent recusal rules. “By pursuing rulemaking rather than adjudication,” the board member, an Obama appointee named Lauren McFerran, wrote in a dissent from the proposed rule, “the Board is perhaps able to avoid what might otherwise be difficult ethical issues.”

When staffers on Scott’s committee reviewed the ethics opinion at NLRB headquarters, they found it lacked substantive analysis of those concerns and of how Emanuel’s earlier conflicts of interest affected them. “A more fulsome public examination of that opinion is in order,” Scott wrote in comments he and a Senate colleague submitted to the NLRB.

The plea went unheeded, and the NLRB issued its employer-friendly rule in February.