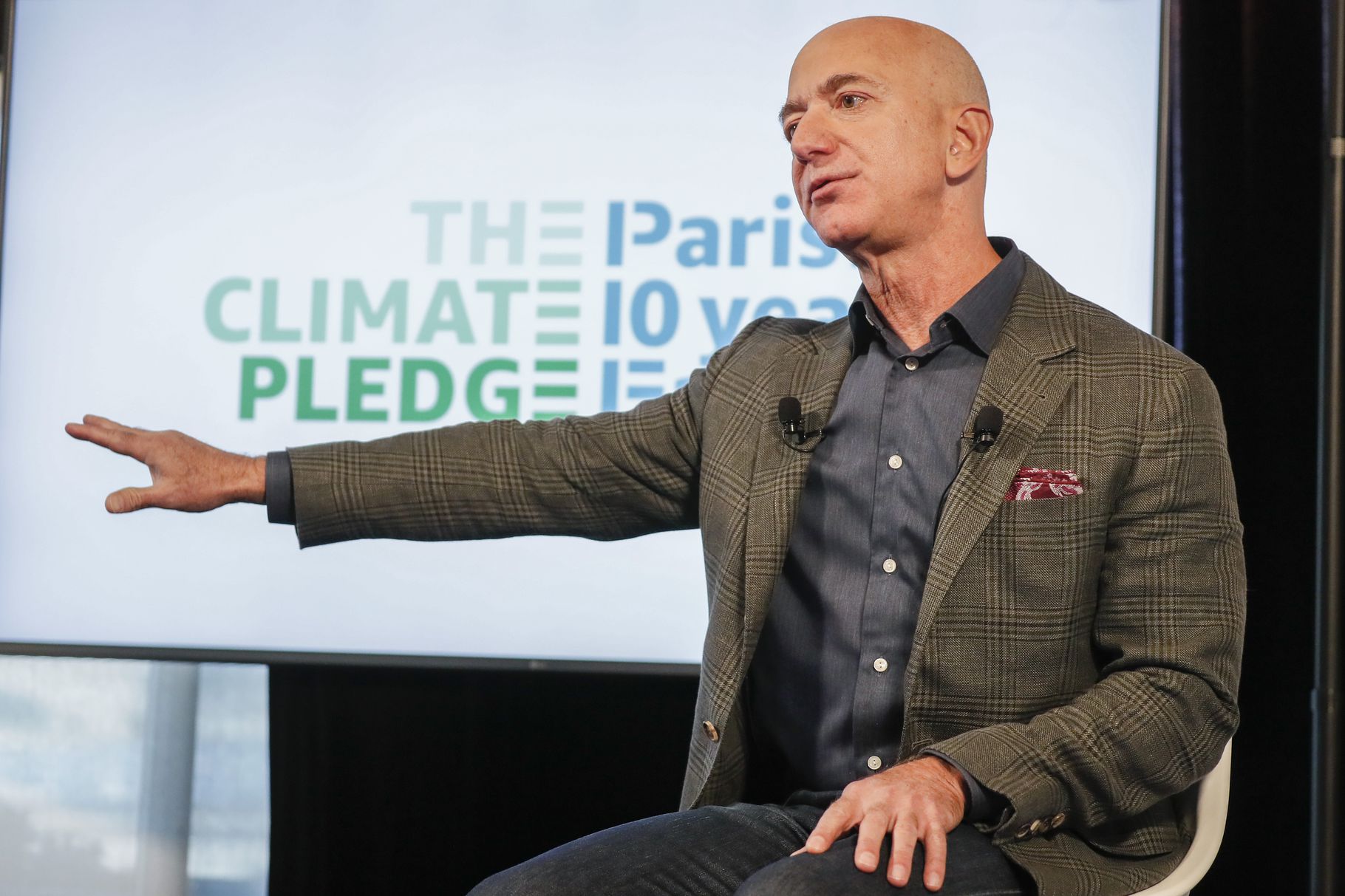

Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos announced his company would take measures to reduce carbon emissions a day ahead of a planned walkout by his employees. Paul Morigi/Getty Images for Amazon

Share

This story was originally published by Pro Publica

As they prepared for last year’s holiday rush, managers at Amazon unveiled a plan to make the company’s sprawling delivery network the safest in the world.

Amazon, which ships millions of packages a day to homes and businesses across America, had seen a string of fatal crashes involving vans making those deliveries over the previous few years. Improving safety, the plan said, was “Amazon’s Greatest Opportunity.”

A key part of the proposal was a five-day course that would put new drivers through on-road assessments overseen by an outside organization with four decades of experience in driver training.

But the defensive-driving course didn’t materialize.

Amid the rush of what would become Amazon’s busiest holiday season ever, the class was vetoed. With more than a billion packages shipping in a span of six weeks, the company needed to put drivers to work almost as soon as they were hired, internal documents show.

Get Our Top Investigations

“We chose to not have onroad practical training because it was a bottleneck” that would keep new drivers off the road, noted a memo written by a senior manager in the logistics division just after the peak season wrapped up.

In just a few years, Amazon has built a delivery system that has disrupted a decades-old business dominated by FedEx and United Parcel Service. But in its relentless drive to get bigger while keeping costs low, Amazon’s logistics operation has repeatedly emphasized speed and cost over safety, a new investigation by ProPublica and BuzzFeed News has found.

Time after time, internal documents and interviews with company insiders show, Amazon officials have ignored or overlooked signs that the company was overloading its fast-growing delivery network while eschewing the expansive sort of training and oversight provided by a legacy carrier like UPS.

One such incident hit particularly close to home. Just as the company began to build its delivery network six years ago, a delivery van carrying Amazon packages struck a cyclist in a San Francisco suburb. The cyclist was Joy Covey, Amazon’s first chief financial officer. She was killed, leaving behind a young son.

But for all the heartbreak among her former colleagues, the fatal crash did not alter the course the company was charting on delivery. Indeed, the system Amazon was creating would come to rely on low-cost contractors like the one involved in the crash that killed Covey.

In a statement, Amazon rejected the notion that it had put speed ahead of safety, calling the new investigation “another attempt by ProPublica and BuzzFeed to push a preconceived narrative that is simply untrue. Nothing is more important to us than safety.”

Amazon said that in the U.S., it provided more than 1 million hours of safety training last year to its employees and its delivery contractors, though it did not say how many people in its vast workforce — which numbers well in excess of 250,000 employees in the U.S. alone — received training. Amazon also said that last year it implemented “safety improvement projects” totaling $55 million, which would represent about one-fifth of 1% of the $27.7 billion the company spent on shipping last year.

Amazon would not say how many people had been killed this year or in past years in crashes involving its network of delivery drivers. Internal company documents show that Amazon routinely tracks crashes and has developed a corporate protocol for responding to fatalities.

The company, citing a federal safety rate that is not specific to deliveries or even commercial driving, says that its rate of fatal crashes this year is better than the most recent federal rate. But that rate — which divides the total number of miles driven in the U.S. by the number of fatal crashes — encompasses virtually all American vehicles, from a sedan owned by a family to an 18-wheeler owned by a Fortune 500 company.

“Unfortunately,” Amazon’s statement said, “statistically at this scale, traffic incidents have occurred and will occur again, but these are exceptions, and we will not be satisfied until we achieve zero incidents across our delivery operations.”

To trace the history of how Amazon built its delivery network, ProPublica and BuzzFeed News interviewed current and former Amazon employees, delivery drivers and contractors, many of whom requested anonymity because they feared that speaking about Amazon could harm their careers.

Those interviews, as well as internal documents, reveal how executives at a company that prides itself on starting every meeting with a safety tip repeatedly quashed or delayed safety initiatives out of concern that they could jeopardize its mission of satisfying customers with ever-faster delivery.

Investigations by ProPublica and BuzzFeed News this year revealed that drivers delivering Amazon packages had been involved in more than 60 crashes that led to serious injuries, including 10 deaths. Since then, the news organizations have learned of three more deaths.

Amazon, which keeps a tight grip on how drivers working for contractors do their jobs, has told courts around the country it was not responsible when delivery vans crashed or workers were exploited. It is a position that is facing more legal and legislative challenges, as some states seek to force tech companies such as Uber to take more financial responsibility for the contract workers who underlie their businesses.

In the early days of Amazon’s expansion into logistics, executives wrestled over what price to put on safety. One shot down another’s plan to boost safety by giving drivers longer rest breaks and capping the number of packages per route. Those measures would have cost 4 cents per package.

Several years later, an audit team found that some delivery contractors were exploiting drivers or failing to carry enough insurance. Amazon chose to lay off the head of the audit team, according to people familiar with the matter.

Last year, as the number of packages soared, one manager simply dialed up the speed on the conveyor belts in a delivery station, injuring workers and prompting an internal investigation, documents show. To get the ever increasing volume of packages to customers, Amazon rushed new drivers through the hiring process, adding one who suffered from night blindness and another who acknowledged medicinal use of marijuana, company documents and interviews show.

This year, Amazon has even more riding on the logistics empire it has built, according to company documents. For the first time, the company anticipates delivering more than half of its holiday season shipments — hundreds of millions of packages — using its own network of independent contractors and employee drivers.

Inside Amazon, some employees have worried that the company loads up drivers with too many packages and expects them to complete deliveries at an inhuman pace.

“The means to the end is something they don’t care about,” said a former Amazon manager who quit in frustration in 2017. “If we are forcing these drivers to go like bats out of hell to get this stuff all over town, that’s OK, because we are making it great for our customers. The human cost of this is too much.”

Fear of Extinction

In Amazon’s earliest days, its founder and CEO Jeff Bezos dropped packages full of customers’ book orders at the post office himself. As the company got bigger, it began relying on UPS and FedEx as well as the U.S. Postal Service.

All of it was in service of Bezos’ core idea that “delighting” customers should always be the priority.

“I tell everybody at Amazon.com to wake up every morning absolutely terrified, drenching in sweat, but that they should be afraid of something very precise. They should be afraid of customers not of competitors,” Bezos said in an April 1999 interview with Charlie Rose. “And the reason is that it’s the customers we have a relationship with. Our customers are loyal to us right up until the second that somebody else offers them a better service.”

This ethos continues to power Amazon’s disruptive culture. The moment the company stopped embracing speed, action and risk-taking, Bezos argued, was the day it was headed for the corporate boneyard. To avoid extinction, Amazonians needed to work every moment like it was “Day 1.” That’s the name he gave to one of the office towers that make up the company’s headquarters in Seattle.

Bezos had long entertained proposals from managers calling for Amazon to exert more control over the “last mile,” the final leg of delivery between the warehouse and a customer’s doorstep. In the 2000s, Amazon, dissatisfied with the inflexibility of UPS and FedEx, for whom Amazon was just one of a long line of customers, started experimenting with using small and regional carriers to deliver packages.

Our investigation found Amazon escapes responsibility for its role in deaths and serious injuries even though the company keeps a tight grip on how third-party delivery drivers do their jobs.

After a 2010 snowstorm in the U.K. disrupted the Royal Mail and led to the late arrival of many holiday deliveries, executives within Amazon realized that their dependence on major carriers there and in the U.S. could trigger the kind of extinction event that Bezos warned about. They needed to build a delivery network they could control.

Amazon didn’t want to simply copy FedEx and UPS. It wanted to be faster, cheaper, and, someday, bigger, and it saw technology as its competitive advantage. In early 2013, the head of the transportation group was a longtime Amazonian named Girish Lakshman. His team, responsible for creating delivery routes globally, was under pressure. Because Amazon was building its delivery network from scratch, it had little data about how to plan the most efficient routes. In early experiments, some drivers were overwhelmed by the sheer number of packages, while others had too little work, according to people in the group.

Around June 2013, Lakshman proposed in a white paper that drivers be paid on a per-package basis and that the number of packages per route be capped to ensure that drivers had adequate breaks and enough time to deal with weather or unexpected traffic delays, according to people familiar with the matter. He estimated these measures would cost an additional 4 cents per package.

To get the proposal through, Lakshman needed buy-in from his new boss, Dave Clark, who had just been elevated to become Amazon’s new logistics and operations chief after fine-tuning the company’s warehouses.

Although Clark was open to ideas for improving safety, he questioned whether the 4-cent-per-package safety measures would actually make deliveries safer, according to two people familiar with the debate. He argued Amazon could find better ways to incentivize safe behavior, these people say, and preferred paying for delivery on a per-route basis and not locking the company into a structure that could prove expensive as Amazon scaled up from delivering millions of packages to billions, these people say.

Clark, now a senior vice president and among Amazon’s highest-ranking employees, called Lakshman’s proposal “garbage” before rejecting it, according to the people familiar with the proposal.

Last week, Lakshman forwarded a reporter’s questions about the 4-cent safety proposal to Clark. An Amazon spokeswoman, Rena Lunak, said any characterization suggesting “contention” between the two men over the white paper was “simply not true.” Lunak said hundreds of white papers like the one prepared by Lakshman are reviewed every day at Amazon. She defended Clark as a leader with “backbone” and added that “being direct and clear as a leader through these types of white paper reviews is a benefit, not a defect.”

Clark, in a separate statement, said the company has “learned a lot in the years since we started delivering packages and we’ll continue to learn more… We’ve always had a focus on safety and continuous improvement and that won’t change.”

It was a few months after that debate that the life of the company’s first chief financial officer, Joy Covey, came to an end in the collision on a hill in San Francisco’s South Bay suburbs.

Covey, 50, had gone out for an afternoon bike ride. As she zipped down a forested stretch of Skyline Boulevard on Sept. 18, 2013, a delivery van turned left directly into her path.

“I heard a scream, immediately followed by a crash,” the van’s driver later testified. Covey was killed.

The white Mazda had been sent out by OnTrac, one of the regional carriers Amazon had been using to gain a measure of shipping independence. The driver, a subcontractor, later testified that the “vast majority” of his deliveries were for Amazon, but he was not using Amazon’s routing technology or directions. OnTrac did not respond to written questions seeking comment. Insurers for the company, its contractor and the driver eventually paid $6.25 million to settle the case filed by the guardian of Covey’s son.

Covey’s death made the risks of last-mile delivery more obvious — and more personal. In Amazon’s early days, it was Covey who had persuaded Wall Street to buy into Bezos’ long-term vision when the company was losing money. After leading Amazon through its initial public offering, Covey left in 2000 to become an investor and philanthropist.

When Bezos spoke at her November 2013 memorial service, he choked up, the author Brad Stone wrote in his book, “The Everything Store.”

“Joy and I talked often about a day in the future when we would sit down together with our grandkids and tell the Amazon story,” Bezos said.

The crash could have caused Amazon to rethink the way it handled safety issues but it didn’t. Senior managers in the logistics division at the time regarded the death as a just another traffic accident, according to three people familiar with their conversations.

Just weeks after Covey’s memorial service, Amazon faced another holiday delivery debacle — this time in the U.S.

In the third week of December, a million people signed up for Amazon Prime memberships, and orders surged to record levels. UPS was swamped, and customers were left on Christmas Eve without presents they were expecting for the next morning. Amazon, devoted to “delighting” customers, had instead incensed them.

In the aftermath, Amazon doubled down on a delivery strategy intended to give it more control over deliveries and ensure that such a fiasco was never repeated. Within weeks, Amazon’s newly formed logistics division circulated a planning document that called for expanding to 10 new metro areas, including New York, Washington and Philadelphia. Given that the company was “behind in all regions,” the memo asked, how could the delivery network “launch faster?”

The confidential directive details Amazon’s plans to use “disruptive” technology to onboard and monitor delivery contractors. The goal, it says, was “supporting rapid expansion — never blocking it.” In its 20 pages, it mentions reducing costs nine times; it mentions safety just once.

“Maniacal Focus”

In June 2015, Agnes Acerra was crossing a street in Hoboken, New Jersey, when a white Ford van filled with Amazon packages turned left and ran over her. The 89-year-old, who had formerly worked as a sales clerk at Macy’s flagship store in Manhattan, suffered a broken pelvis, a concussion and a broken leg. She died soon after from internal hemorrhaging.

The driver was ticketed for failing to yield, and after an ambulance carried Acerra away, he finished his delivery route. The company that employed the driver, SDS Global Logistics, was one of the small independent firms that Amazon had chosen to deliver packages to customers.

As part of the sprint to build out its network, Amazon had initially considered operating its own fleet of UPS-sized trucks. But in an experiment in San Francisco, the trucks had difficulty navigating the city’s narrow, hilly streets, former Amazon managers recalled. Independent third-party contractors with their own fleets of cargo vans proved a cheaper, more nimble option.

Unlike OnTrac or UPS, these contractors operated out of Amazon’s own delivery stations; they carried only Amazon packages; and they followed the instructions of Amazon routing software, which dictated the number of packages loaded onto their vans and the order of the stops on their routes. They were held to extremely high performance standards, including a requirement that 999 out of 1,000 packages be delivered on time.

The costs of acquiring and maintaining the vans would fall to the contractors, not Amazon, and unlike the trucks used by UPS, they fell under the weight threshold for regulation by the federal Department of Transportation. That meant they didn’t have to adhere to safety mandates such as vehicle inspections by federal regulators or limits on the number of consecutive hours drivers could spend behind the wheel.

The arrangement gave Amazon considerable power over its contractors. With most or all of their business tied up with Amazon, the contractors had little leverage with which to negotiate on price. Amazon set prices on its own terms, sometimes paying one company significantly less than another for the same route in the same market, a review of contracts shows.

The contracts drafted by Amazon’s lawyers for the delivery companies also shielded the e-commerce giant from just about every imaginable liability. The delivery companies were on the hook for anything that went wrong, from workers complaining they were mistreated or underpaid to pedestrians and drivers hurt in crashes. And when Amazon was sued in such cases, the delivery companies were even responsible for paying all of Amazon’s legal bills.

The same month Acerra died, an Amazon employee in the Seattle headquarters named Will Gordon began building a team that worked to improve route planning and maximize the efficiency of deliveries.

“There was a maniacal focus on increasing shipments per route,” recalled Gordon, who left Amazon in 2016 and is now the founder of a Seattle startup called Latchel, which coordinates rental-property maintenance. “Everything was about getting more shipments per truck. It was the one metric that drove the organization.”

Every delivery company wants to maximize the number of packages drivers deliver, but Gordon said Amazon took things to an extreme. He said the company would have been better off focusing on large packages, which cost more to send through other carriers. Instead, in its race to boost the “shipments-per-route” metric — which he said was far and away the company’s top priority — Amazon stuffed vans with small-sized packages, parcels that could have been more economically delivered by the U.S. Postal Service.

In some metro areas such as Los Angeles, Gordon said, Amazon underestimated the time it took to complete routes by failing to factor in rush hour traffic. This led to harried drivers who felt pressured to rush to complete their routes. Amazon collected an enormous quantity of data about its shipping operation, analyzing practically every possible input on each shipment. Yet one element of delivery was routinely overlooked in the U.S., Gordon said: safety.

“It should have come up more often,” Gordon said.

“Machine-Oriented System”

By late 2016, Amazon had launched delivery stations in most major metro areas, and it was hurrying to expand to smaller cities in order to keep up with demand. As the critical peak season approached, the pace was straining many contractors.

That fall, Amazon invited representatives from more than a dozen contractors to a New Jersey conference room overlooking Manhattan for the company’s first delivery summit. The meeting was supposed to be a forum for constructive feedback about the program. Instead, attendees recalled, it dragged on for hours as contractors barraged Amazon managers with complaints about nearly every aspect of the system they had created.

Contractors protested that Amazon forced drivers to wait for hours, then overloaded them with boxes and expected them to complete deliveries in an unrealistic time frame. Drivers quit constantly because the job, which often required them to deliver as many as 300 packages a day, was so demanding. Amazon’s unreliable routing and navigation software only made matters worse, according to two people who attended.

Amazon required delivery contractors to use an app called Rabbit, which not only scanned packages but also told drivers which packages to deliver in which order and provided turn-by-turn directions. But the company began using the in-house app before it was ready, former Amazon employees say. Trip O’Dell, one of the architects of Rabbit, called it an “MVP” — software jargon for a “minimally viable product.”

O’Dell recruited an idealistic band of designers to Amazon with the pitch that they were going to make life on the road better for drivers. But Paula Wood, a member of this group, quickly became disillusioned with the technology and Amazon’s commitment to drivers. “It was ludicrous to expect drivers to be able to deliver in the tiny slices of time,” Wood said. “They put humans into a machine-oriented system.”

Wood said that on many routes, drivers didn’t have enough time to go to the bathroom or eat, so they skipped meals and breaks and urinated in bottles. Navigation directions were terrible, she said. Drivers were, for example, directed to curbs that were no-stopping zones during rush hour. The Rabbit sent drivers on dangerous paths, back and forth across busy roads, she said, full of repeated U-turns and left turns, like the ones that killed Covey and Acerra.

Research shows left turns can be risky because they require the driver to cross oncoming traffic, and the pillar between the windshield and the door can make it harder to see pedestrians in crosswalks. The algorithm that powers the turn-by-turn directions UPS uses, by contrast, programs out most left turns.

One former Amazon manager recalled watching a driver on a ride-along pounding furiously on the phone while shouting: “I hate this Rabbit! I hate this Rabbit!”

The company said there are “hundreds of technologists at Amazon who are focused on continuously improving the functionality of the Rabbit app” and, based on feedback from drivers and contractors, it has made more than 500 changes this year alone. Amazon added that it has “included functionality to avoid left and U-turns, even if that means a route takes longer” and that drivers “have always been able to stop at any time to take a bathroom break.”

Penny Register-Shaw, a former FedEx lawyer, was hired by Amazon in September 2016 to whip the delivery contractor program into shape, according to four people familiar with the program at the time. One of her first orders of business was to attend the New Jersey summit, where at least one contractor said he felt like at last someone was listening and would present the plight of drivers to Amazon management.

But Register-Shaw had trouble persuading her bosses. She spoke gently and slowly, the cadence of her voice reflecting her Tennessee upbringing, and was interrupted so frequently by her new Amazon colleagues that she rarely finished a sentence, according to several people who worked with her.

Register-Shaw and her team proposed changes to make deliveries safer for both drivers and the public, according to interviews with people familiar with the group. They recommended a drug testing regimen for contractor drivers who were already on the road. The plan called for random tests “so drivers would not know when they were coming,” said a person familiar with the white paper proposing the tests. But the idea was nixed by higher-ups, according to people familiar with the matter.

Asked about this account, Lunak, the Amazon spokeswoman, initially said it was false. But when asked additional questions about the company’s drug testing practices, she explained that Amazon required “comprehensive” pre-employment drug screening and said that drivers “are subject to additional screening if there is reasonable cause or if there is an accident.”

At some delivery stations, drivers had to retrieve their vans from distant lots before picking up their packages, and that often put them behind schedule before they even began their routes, according to two people on Register-Shaw’s team. They said her group pushed for closer parking and when that did not happen, the group recommended that drivers’ travel time be taken into account when planning shifts. That idea did not move forward either.

Members of Register-Shaw’s team were mortified by reports of drivers urinating in bottles rather than taking bathroom breaks, and even defecating outside of customers’ homes. “Humans don’t do that unless they’re under tremendous pressure,” a former member of the team said.

In early 2018, an audit team that Register-Shaw had assigned to evaluate the growing pool of delivery contractors working for Amazon reported that it had discovered dozens of the companies were out of compliance.

Some contractors didn’t have the amount of insurance Amazon required, and others weren’t paying for legally mandated overtime and rest breaks, according to several people familiar with the audit.

The findings posed a problem for Udit Madan, the executive Amazon had just put in charge of its last-mile program, according to people familiar with the audit team’s work. Putting as many drivers on the road as possible every day was a priority for Amazon. In one delivery station, the package count nearly doubled overnight, according to a manager who worked there; the e-commerce giant could ill afford to lose established delivery partners to carry those shipments to the customer.

“You felt the pressure,” said a person close to the audit team. “If you take 200 vans off the street, that would have an impact on the customer promise of two-day delivery.”

Register-Shaw eventually took the fall, resigning rather than firing members of the audit team, according to a person familiar with the matter. The head of the audit team was forced out soon after, and the team was dispersed. When asked to comment about the details in this report, Register-Shaw, who now works for Amazon’s largest retail competitor, Walmart, answered, “I wish I could have done more.”

Amazon disputed aspects of this account, saying that its monitoring of delivery contractors has improved since the leadership reshuffle. “Due to issues with the auditing program at the time, the team was moved to a centralized compliance organization,” Amazon said in a statement. “That move and new leadership, created immediate results, including increasing the scope and rate of the audits.”

Madan did not respond to questions sent through an Amazon spokesperson. The company said it monitors its contractors’ compliance with the law and expects those who are not performing to correct their problems within 30 days or “risk having their contract terminated.”

“Our transportation network is not about anyone working faster than is safe,” Amazon said in a statement. “It’s about processes and our overall operations network coming together to be able to serve customers.”

Stuck in the Mud

In June 2018, Amazon invited the news media to Seattle for an event at a picturesque venue overlooking Elliott Bay. Instead of unveiling a new drone or other high-tech project, Dave Clark, standing in front of a van, announced that the company was rebooting its delivery network, shifting much of its package volume to smaller contractors.

The new firms would manage between 20 and 40 routes apiece, compared with hundreds run by the bigger contractors Amazon had previously signed up. Amazon would make it as easy as possible: It helped new delivery companies with legal paperwork, arranged for leases of new vans emblazoned with the company logo and even recommended preferred vendors to handle insurance and payroll. Would-be entrepreneurs — some with no experience in logistics — rushed to sign up for the program, which handed Amazon even more control over nearly every aspect of delivery while also increasing its financial leverage over the tiny firms.

At the same time the program was gearing up, at Amazon managers were putting the final touches on an ambitious road safety plan, the one that aspired to make the company “the safest last mile carrier in the world.”

The July 2018 document, World Wide Amazon Logistics On Road Safety Plan, emphasized that achieving that goal would require a radical shift in the company’s safety culture. Each delivery station, for example, would have a “number of days safe” sign on the wall, all vehicles would be professionally inspected every year for roadworthiness, prospective hires would face more vetting and Amazon would implement a zero-tolerance policy for serious safety violations.

It also detailed the plan in which instructors from the National Traffic Safety Institute would teach new drivers a “defensive driving curriculum.”

“Training is a critical first step to creating the right culture, building a shared vocabulary, and developing the right behaviors,” the plan said.

Although Amazon managers overseeing delivery initially greeted the goals of the safety plan with enthusiasm, according to one person familiar with the plan, their tune changed as the all-important peak season approached.

Between Thanksgiving and Christmas 2018, Amazon roughly doubled its shipments nationwide from the previous year, surpassing the billion package mark for the first time. The company encouraged its delivery contractors to recruit as many drivers as possible. Amazon for its part hired an additional 3,949 employee drivers in the space of just a few weeks, renting “nearly every van in the United States” for them to drive, internal documents show.

In the end, the peak 2018 season looked very little like what the safety team had laid out in its proposal just four months earlier.

Employees charged with inspecting new delivery stations for safety compliance noted in an internal memo that they had been unable to visit every new station prior to launch. In some stations they did manage to visit during peak season, they were chagrined to discover scenes of chaos: inadequately trained managers, severe understaffing, haphazard traffic flows for delivery vans entering and exiting stations, and packages scattered on the floor.

Many of the stations were little more than tents erected in suburban parking lots, referred to internally as “Carnival” stations. Often, the sites suffered from a shortage of bathrooms, unsanitary working conditions, insufficient heat, a lack of ice scrapers for vehicles and poor drainage, according to internal memos and interviews with current and former Amazon employees. Some stations flooded, drivers and packages were “exposed to wind, rain, and snow,” and some parking lots became mired in thick mud that stranded delivery vans. One memo offered a solution for the mud: Put bags of kitty litter in every van.

Human resources employees complained that they “operated with a skeleton crew” while being tasked with recruiting and hiring thousands of seasonal employees who were subsequently taught how to do their jobs by instructors who “lacked the requisite skills to train someone.”

Last January, various departments within Amazon’s logistics operation shared memos detailing “lessons learned” during 2018’s peak season.

Managers overseeing the delivery contractors lamented that there was still “no current metric to measure safety” among their tens of thousands of drivers. During peak, those managers noted, drivers were frequently caught speeding through parking lots, yet there was no way to hold them accountable.

A group at Amazon responsible for education and training, meanwhile, reported in its memo that it had fallen far short of its hiring goals for driver trainers. Nearly three weeks after peak season ended, 24 delivery stations still didn’t have any driver training at all, the memo said.

In a statement, Amazon said all delivery drivers are required to undergo training “before they are able to deliver even one package.” The company also said that the use of interim facilities such as Carnival stations is “standard practice” in the logistics industry and that it is currently converting those sites into permanent delivery stations.

Internal Amazon documents show that managers in charge of the delivery contractor program worried that the pressure on the system would only intensify during the 2019 holiday rush, as Amazon planned to build 80 new delivery stations, triple the size of its delivery contractor program, and, in April, make overnight delivery the default option for Prime members.

In a memo filed this past January by the group overseeing delivery contractors, one manager warned, “We need a greater focus on safety.”

Fantastic Plus

Today, Amazon’s delivery operations are under increasing scrutiny as the press, politicians and Amazon’s own former managers question the company’s aggressive approach to logistics.

Citing the BuzzFeed News and ProPublica investigations on the hidden human toll of Amazon’s delivery network, U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal in September lambasted the company. On Twitter he called Amazon “callous,” “heartless” and “morally bankrupt.”

Amazon’s Clark tweeted back, “Senator you have been misinformed.” He wrote that the company took responsibility for its actions and had requirements for safety, insurance and “numerous other safeguards for our delivery service partners which we regularly audit for compliance.”

Amazon refuses to disclose the names of the contractors it uses to deliver its packages, calling it “competitive, confidential business information.”

A few days later, Blumenthal and two other senators, Sherrod Brown and Elizabeth Warren, demanded answers from Bezos.

“Innocent bystanders — as young as 9 months old — have lost their lives and sustained serious injuries from drivers improperly trained and under immense pressure by Amazon to meet delivery deadlines,” the senators wrote in a September letter to Jeff Bezos. “It is simply unacceptable for Amazon to turn the other way as drivers are forced into potentially unsafe vehicles and given dangerous workloads.”

In the run-up to this year’s peak season, Amazon has adjusted the benchmarks it uses to monitor the performance of its delivery contractors, introducing new safety metrics, according to interviews with delivery contractors and reviews of scorecards used to measure their performance. For example, Amazon began tracking the use of seat belts by drivers and incorporating that data into weekly scores for delivery businesses. Data is collected through an app that most drivers must use and that monitors speed, acceleration and braking, among other metrics.

Every week, Amazon rates the performance of its more than 800 delivery contractors. Those that earn the highest scores — identified by Amazon as “fantastic” or “fantastic plus” — receive bonus pay, which some delivery contractors say can represent the difference between losing money or turning a profit.

In a scorecard from November, safety represented 17% of the total score, compared with 33% for a category labeled “quality.” Amazon said that if a delivery contractor doesn’t have a high combined score in its safety and compliance metrics, it cannot reach “fantastic” or “fantastic plus” overall, and that firms that consistently receive low scores can be threatened with termination or see their routes reduced.

In the end, Bezos didn’t reply to the senators’ letter. Instead, a company lobbyist did. He wrote that Amazon empowered hundreds of small businesses through its delivery contractor program and outlined safety and labor compliance tools that he said went far beyond what’s required by law.

“Safety,” the lobbyist wrote, “is Amazon’s top priority.”

One month after that letter was sent, a contractor delivering Amazon packages in a suburban Chicago townhouse complex turned left on a private drive, striking a toddler who had wandered into a puddle in the roadway.

“She didn’t see him,” said Deputy Chief Ron Wilke of the Lisle Police Department, which is still investigating the crash.

The 23-month-old boy died at the hospital that same day.