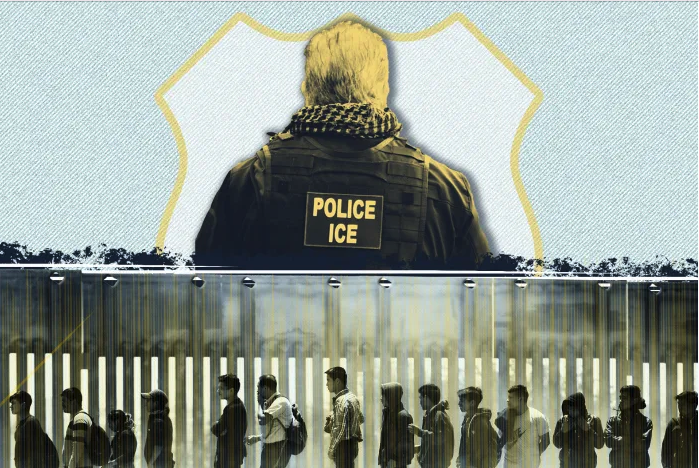

(Photos: Bryan Cox/U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement via Getty Images & Mario Tama/Getty Images; Illustration: Ian Hurley/Pacific Standard)

(Photos: Bryan Cox/U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement via Getty Images & Mario Tama/Getty Images; Illustration: Ian Hurley/Pacific Standard)

Share

A Midwest Community is Raided

Immigrants all over the United States are part of communities; they’re workers, parents, children, consumers, etc. They’re workers who were overlooked for COVID-19 support and larger policy issues. It’s more likely that immigrant workers will face fear of deportation rather than an enforcement action against an abusive exploitative employer. Lately, immigrant workers are again overlooked as article after article highlights a significant labor shortage all over the country.

I moved to Minnesota nine years ago and have been running Workday for the last four years. I’ve been slowly learning about Greater Minnesota and the migrants that call it home. As the narrative around labor shortages continues, I am struck at how migrants are overlooked. A major factor in these shortages is simply that a significant number of workers have been deported. The rhetoric that led to these hard line inland deportation policies never considered the possibility they weren’t just deporting immigrants, they were also deporting in-demand workers.

At least in Greater Minnesota, you can’t make up for these workers easily and quickly. It’s also a confusing situation since these communities depend on immigrant labor and are more likely to have embraced the xenophobic nativism of the Trump era.

In the next year, we will tackle these issues more directly. Our focus will be on the feelings and experience of those that are navigating these very local and very global dynamics.

Postville, Iowa, is a good example of how devastating the push and pull of national immigration policy can be for local communities.

On the tenth anniversary of the May 12, 2008 raid in Postville, Iowa, I rode along with Jewish Community Action (JCA) to an interfaith memorial ceremony and reflection. What came across was how devastating and violating it was to folks. What I have learned spending more time in rural areas is that the connective tissues among people in smaller communities are more taut so any disruptions tend to be disproportionate and lasting.

The interfaith service started with memories of that day.

The sound of helicopters erupted over the community. Folks talked about how assaulting it felt to have black-clad armed government agents descending on their otherwise quiet rural town of 2,200. They came to detain nearly 400 immigrant workers from the Agriprocessors meatpacking plant. Witnesses from the period described immigrants getting rounded up and temporarily housed in livestock areas. Customers, friends, and parishioners had abruptly been abducted by the federal government. The connective tissue was snapped and broken.

Those that had woven their lives within immigrant communities ten or so years later remained grief stricken and devastated.

The same story has happened all over the Midwest.

ICE Expands Into the Midwest Under Trump

Trump tipped the tense balance between an increasingly militarized and hostile immigration system and an overwhelming demand for exploitable immigrant labor. Trump chose to weaponize fear, and thus he weaponized ICE to generate state-sponsored terror. What resulted was families and workers were deported at an unprecedented rate.

The power and footprint of ICE expanded into the interior of the country. Instead of stopping migrants at the border, ICE officials seemingly hunted for migrants all over the Midwest. In practice, what this means is the destabilization of settled families, the communities they are a part of, and the industries that depend on their labor.

University of Minnesota Professor of Chicano and Latino Studies Jimmy Patiño, has spent his career focusing on the history of the border patrol. In discussing elements of this essay he noted that for migrants targeted by ICE these inlad actions have amounted to “state-sponsored terror.”

According to The Washington Post, one of the ways that ICE expanded was partnering with local sheriffs. Under Trump, sheriff partners grew from about 35 in 2017 to more than 140 earlier in 2021. As interior deportation has decreased, this apparatus has not been shut down, likely extending the practice of targeting immigrants or people perceived as immigrants with low level arrests.

While the Trump era and the progressive response to the deportation regime has centered and legitimated the belief that immigration policy is broken and needs fixing, Patiño is quick to point out the system can’t be reformed since its doing exactly what it is designed to do. He further elaborated and explained that the deportation regime “creates so-called illegal people to create a vulnerable workforce that businesses have been reliant on since the border patrol was created in the 1920s.”

The Washington Post reported improvements under the Biden administration. Immigration arrests in the interior of the United States fell in fiscal year 2021 to the lowest level in more than a decade, roughly half the annual totals during the Trump administration. While an improvement, the complex levers that Trump imposed over for years will be monumental to untangle.

The Biden administration is not without its critics. Immigrant advocacy groups are angry over the mass expulsion of Haitian migrants from a makeshift camp in Del Rio, Tex. in September, as well as plans to restart the Trump-era “Remain in Mexico” policy

The plan to continue the Remain in Mexico plan for amnesty seekers is especially aggravating.

We Can’t Hire Anyone!

At Workday, we’ve noticed a bewildering pattern in the “Great Resignation” narrative. Everyone seems to have forgotten that immigrants do things, often things that nobody else wants to do. Restaurant, supply chain, and construction work is predicated on the exploitation of immigrant labor. So yes, if a lot of immigrants are deported and discouraged from crossing, you lose a lot of workers that have been rooted in community, and also those that replenish the labor supply. Turns out, it is possible to deport your way into a labor shortage.

According to a study by the Pew Research Center, typically the U.S. welcomes roughly one million immigrants, and roughly three-quarters of them end up participating in the labor force. In 2020, that number dropped to about 263,000. The report also notes that 77% of migrants have a legal status. From the report:

“In 2017, about 29 million immigrants were working or looking for work in the U.S., making up some 17% of the total civilian labor force. Lawful immigrants made up the majority of the immigrant workforce, at 21.2 million. An additional 7.6 million immigrant workers are unauthorized immigrants, less than the total of the previous year and notably less than in 2007, when they were 8.2 million. They alone account for 4.6% of the civilian labor force, a dip from their peak of 5.4% in 2007. During the same period, the overall U.S. workforce grew, as did the number of U.S.-born workers and lawful immigrant workers.”

According to an analysis in Vox, the industries currently facing the worst labor shortages include construction, transportation and warehousing, accommodation and hospitality. and personal services businesses like salons, dry cleaners, repair services, and undertakers. All four industries had increases in job postings of more than 65% when comparing the months of May to July 2019 to the same time period in 2021. Immigrants make up at least 20% of the workforce in those industries.

According to the New York Times, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce is calling for an expansion of visas and guest work programs. However, in the current political environment and with the specter of a second presidential election dominated by Trump, it’s hard to understand how this will get better.

At some point, legislators will do something to increase access to visa programs that have already dramatically increased in use. While the fear of ICE and workplace raids is consistent, enforcement against labor abuse is rare, and that’s why we want to spend more time understanding and documenting what is happening. The future of immigration will continue to be inland and Midwest. Even if federal soldiers stay away, there continues to be growing hostility to immigrants on the ground. This economy will continue to need these workers while simultaneously conspire against their dignity and rights, and we will do our best to report on it.