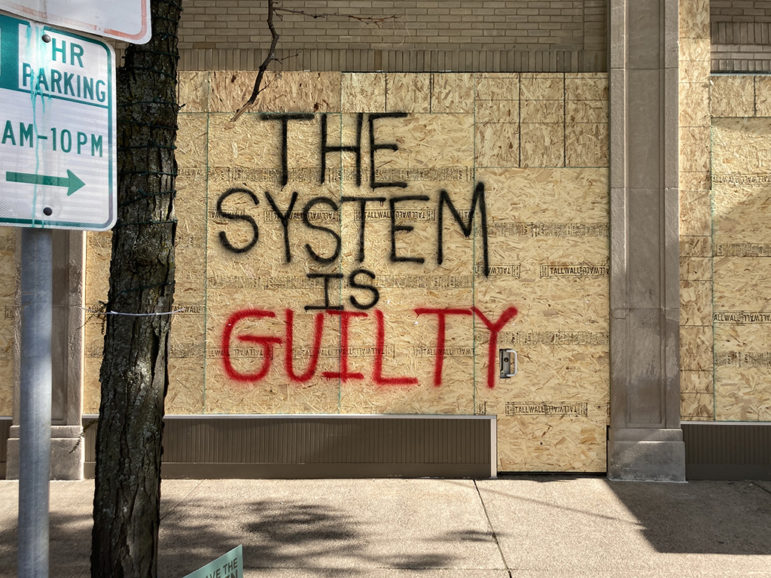

Artwork by Kah Yangni.

Share

Artwork Credit: Kah Yangni

Beginning with the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin on May 25, 2020, the world has witnessed a constant barrage of violent behavior and hateful rhetoric from police and law enforcement across the United States.

This is the latest iteration in a longstanding tradition of racialized police violence. While claiming to protect the community and keep us safe, police have, instead, repeatedly targeted protestors and terrorized communities of color with aggressive and even fatal violence.

The breadth of this police violence has demonstrated that this is not the case of just a “few bad apples.” Instead, it is the latest evidence that violence against particular communities is inherent to what police do; it is systemic. In this climate, it has become clear that a fundamental transformation in the way we think about police is long overdue and the Minnesota labor movement has an important role to play in that work.

As a Minnesotan, an historian, a union member, and an abolitionist, this issue hits close to home. While I became a union member before I became an abolitionist, I have been both for more than a decade. For me, these experiences have been intertwined.

I had my first union job as a teaching assistant at the University of Illinois. The year that our union went on strike (and won!), I was teaching in a prison. Between steward’s council, bargaining sessions, and strike committee meetings, I would drive an hour outside of town to teach the history of the civil rights movement to incarcerated men in a medium-maximum security facility.

Our class discussions were some of the most thoughtful and engaged that I have experienced in my fifteen years of teaching. But when class was over, my students lined up to return to their cells, led by prison guards who called them “boy” and took other opportunities to embarrass shame, and disrespect my students in front of me and their other teachers.

Those guards weren’t “bad apples,” they were just doing their job. In the view of the prison, it was important for the guards to remind my students (and their teachers), that they were prisoners, not men. These interactions made me very uncomfortable. Especially because it was not lost on me that these guards were my union siblings.

At the same moment that I was building solidarity with other workers on campus, fighting for our administrators to see us as more human, I was witnessing the dehumanization of my students at the prison at the hands of fellow union members. This was not just because some of the prison guards were jerks (they certainly were), but because they system itself required it be that way.

Now, years later, I am seeing the same system of dehumanization at play in the streets of Minneapolis. Like with the prison guard, there is a certain level of dehumanization inherent to what police do.

What this means is that both those who interact with police and also police officers themselves are caught in a cycle of dehumanization.

In a piece I wrote years ago that discussed my union’s decision to break ranks with AFSCME (the union that represents most prison guards) and support the closure of a federal supermax prison in Tamms, Illinois, I explained a vision of union solidarity that seems relevant now:

Ultimately we felt that supporting working people shouldn’t mean we also support the ill effects of their jobs….Solidarity doesn’t just mean “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.” It means recognizing how our struggles are connected.

We support the closure of Tamms because it violates the human rights of prisoners and guards. Nobody should have to work in an institution of torture. Solidarity means that we push for fellow workers to have good jobs that contribute to the well-being of our communities, jobs that don’t exploit and dehumanize us. This is the kind of solidarity we want to see grow in the labor movement.

To me, addressing the harm of policing is certainly a labor issue and we should be fighting for a labor movement free from jobs that harm and dehumanize us as workers as well as those with whom we interact. We have that opportunity in Minnesota right now.

Since George Floyd’s murder, more and more people in the United States are recognizing that modern policing has failed to keep communities safe. In the face of that reality, a mass movement has emerged, led by BIPOC youth and activists on the ground who are calling on our communities to divest, defund, and abolish the police.

In a world where public safety has become synonymous with police, imagining something different can seem almost impossible. And yet, every day those imaginings are being put into action on the ground across the nation. Communities have been building systems of support, mutual aid, and crisis care for one another outside of the criminal punishment system for decades. Even more importantly, those imaginings have the potential to actually make ALL of us safer.

In places like Minneapolis, institutions and local political figures are taking this message seriously. The labor movement is one of the most important institutions working class communities rely on, and we have an opportunity to be on the right side of history here. Because the grassroots work taking place in Minneapolis is leading the nation right now, the Minnesota labor movement has an opportunity to set the tone for the rest of the world. National union leadership is not going to lead on this issue.

Minnesota labor already started down this path when locals, union members, and workers’ centers spoke out in support of the protests. Unionized drivers of public buses in ATU Local 1005 even refused to aid police in transporting arrested protestors, which is exactly the kind of action our unions should be taking in this moment.

The Minnesota labor leadership took a different approach when multiple labor organizations in Minnesota issued statements calling for the resignation of the Minneapolis police union President Bob Kroll and the overhaul of the entire Police Officers Federation of Minneapolis. Most coverage and discussion have focused primarily on first part and less on the second, even though the call to overhaul the Minneapolis police union is by far the most important move the labor establishment has made in the wake of George Floyd’s murder.

The focus on Kroll is expected, given that the call for him to resign fits nicely into the “bad apple” narrative that puts the blame on individual actors and absolves the system as a whole.

But Kroll’s position in union leadership is an indication that the entire union is, in fact, the bad apple. Kroll’s long history of racism and violence is well documented. During his three decades on the force, Kroll has been the subject of at least 20 internal affairs complaints and multiple lawsuits. But, rather than the exception, he represents the rule. And the key word there is “represent.”

The police have elected Kroll three times over to their highest office; he is the chosen representative of the force. As union members know, we elect our leadership to represent us, our values, and our interests. Bob Kroll has held elected leadership positions in the federation since 1996.

Kroll’s attitude and behavior reflect the attitudes and behaviors of the force more broadly, including Floyd’s murderer Chauvin and his accomplice Thao. Not only has Kroll proudly claimed that (like him) a majority of the police officers who have been elected to the police union board have been involved in police shootings, he also celebrates that none of them were bothered by it.

“Out of the 10 board members, over half of them have been involved in armed encounters, and several of us multiple. We don’t seem to have problems,” he said in April. As the Minneapolis police have come under greater criticism in recent years, rank-and-file police seem to close ranks around Kroll even more.

Kroll’s consistent presence at the top of union leadership for the past two and a half decades illustrates the systemic nature of this problem and underscores how important it is that Minnesota labor has called to not only condemn Kroll but also overhaul the Minneapolis police union.

Unsurprisingly, the focus on Kroll has been received favorably by national labor leadership, while the call to dismantle police unions has not.

In a press release Tuesday, the AFL-CIO General Board followed step with last week’s message from national labor leaders supporting the Minnesota AFL-CIO’s stance on Kroll but also staking their position on the side of police unions. Echoing comments from AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka, the General Board advocated for unions to engage police affiliates, rather than isolate them.

In an interview with Bloomberg last Friday, Trumka claimed that this was “doing what’s hard and meaningful, instead of what’s quick and easy.” While that may sound compelling, the reality is that the labor movement has engaged and stood in solidarity with police unions for decades.

That solidarity has not helped working people stay safe from police racism and violence. Maintaining those alliances is not hard and meaningful; it is business as usual and THAT is what is quick and easy. What is actually hard and meaningful is doing something different: taking a stand against the terror that police have repeatedly inflicted on communities of color.

A shift in consciousness about who police are is necessary in the labor movement. For too long we have mistakenly viewed police as our union siblings. Yes, police have unions; some are even part of our internationals. And, like us, police get paid for their activities by an employer. But make no mistake, this is where our similarities end and they don’t belong in our unions.

Police are not workers, they are collaborators. They are agents of the state and agents of capital, used to suppress workers and enforce the bosses’ will. Working people have faced repeated aggression and violence from police.

Prominent examples in Minnesota go back at least as far as the 1916 Iron Range strike, and include multiple incidents of police violence during the 1930s, including the 1934 Teamsters strike and the 1939 WPA strikes in Minneapolis. In spite of a long national history of police violence that has specifically targeted workers, the labor movement has, with few exceptions, maintained its alliance with police. This alliance is no longer tenable.

After all, these aren’t even good jobs; activity that perpetuates violence and dehaumanization is not work that the labor movement should recognize or sustain, for the sake of those harmed by police and for police themselves. Many officers live with PTSD from what they do. Rather than support a system that, by design, harms the community and the officers, the labor movement should be fighting to eliminate ALL work that dehumanizes us.

Minnesota labor has already proven that we can lead by calling for the overhaul of the Minneapolis police union and the resignation of Kroll. Now is the time to push even further. Take cues from Minneapolis political figures, ATU Local 1005, CTUL, and others by joining the community to develop a vision of accessible, accountable, and effective public safety that exists outside of a criminal punishment system and does not rely on police.

This is not work that can be done overnight but it is work that will result in greater benefits, power, and safety for working people in Minnesota and across the nation. It promises to build a better labor movement and a better world. What we need and want will certainly change, and these suggestions are certainly not exhaustive, but I offer four steps that Minnesota labor unions can start right now in order to engage in this work:

- Issue a statement of support for dismantling the Minneapolis police department and creating a public safety model in Minneapolis without policing;

- Connect to local activist/community groups leading this work;

- Support elected officials who show leadership in envisioning what public safety beyond policing looks like;

- Commit to engaging in deep political education with your members around systemic racism, police violence, and imagining visions of community safety in which no one is disposable. (This Resource Guide is a great starting place)

It was long overdue that the Minnesota labor movement was finally ready to condemn Bob Kroll as a “bad apple”, but, as the other adage goes, the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. The time is now for Minnesota’s workers to heed the growing call to divest from police unions and take action. If there has ever been a moment for radical change (radical meaning from the root), the time is now.

Rather than focus on one bad apple, the Minnesota labor movement needs to join in community efforts to uproot the entire tree of toxic policing in Minneapolis and tend to the new seeds of public safety that are being sown in the moment. Labor can join the community in moving away from the police model of violence, punishment, and surveillance, and instead pursue safety rooted in healing, mutual aid, and community-oriented accountability.

Anna Kurhajec is an historian and educator. She teaches world and U.S. history at Dougherty Family College and Metropolitan State University. She is a member of the Interfaculty Organization (IFO) and lives in Minneapolis, MN.

“Police are not workers, they are collaborators. They are agents of the state and agents of capital, used to suppress workers and enforce the bosses’ will. Working people have faced repeated aggression and violence from police.”

This article is filled with so much hate that I’m wondering if the author has mental problems.

If Minneapolis removes the police and start doing something else entirely, it will not be safe for people and business anywhere in the city. This is just stupid.