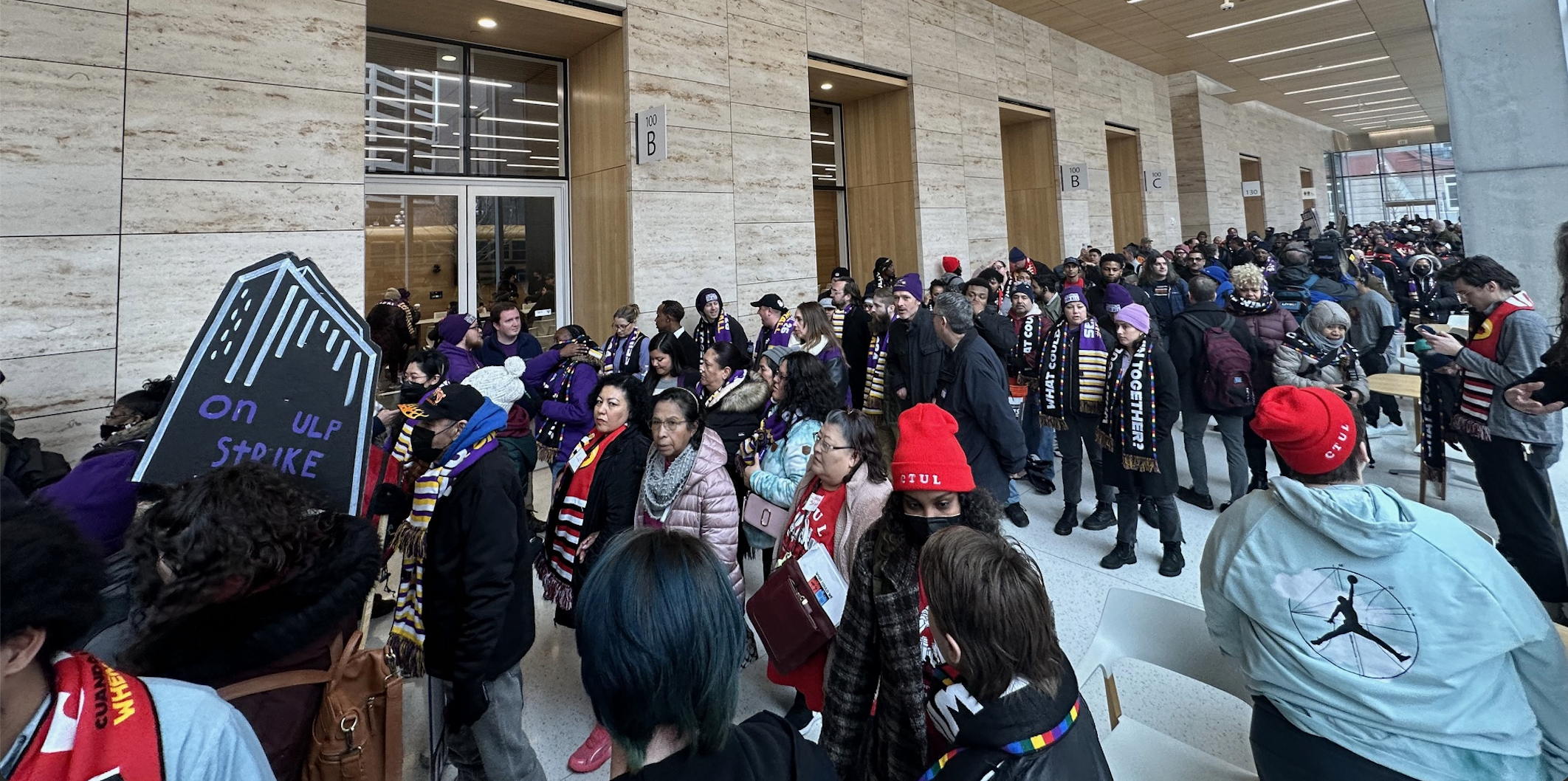

Workers gather outside of a conference room at the Public Service Building in downtown Minneapolis before giving and hearing testimony about the need for a Labor Standards Board. (Photo: Amie Stager)

Share

During the six years Estela Tirado has worked in a salad restaurant in Minneapolis, she has had every job you can imagine: washing dishes, prepping food, working the cash register, and a combination of the above. Despite her hard work, she does not get sufficient paid time off to spend with her six-year-old son, Freddy, who likes to draw and go to the park, and spends the evenings doing homework. “If my son gets sick, I have to use PTO, but when he’s on vacation during summer time, and out of school, I don’t have hours for vacation,” she explains.

This is just one issue Tirado is hoping can be rectified through the creation of a Labor Standards Board, which workers have been fighting to pass in Minneapolis for more than two years. With roots in the Progressive Era, such boards bring together representatives of workers, community members, and business, with the goal of boosting labor standards in specific industries. They are designed not only to improve conditions, but to give workers a voice, including those like Tirado, who do not have unions, but certainly have the will to fight for a better life.

“I’ve been fighting for the Labor Standards Board, because I’ve lived through a lot of injustices,” Tirado tells me over Zoom, while sitting in her car with an interpreter. Freddy is in the back seat, and she speaks openly about her workplace struggles in front of him. “I’m proud we are fighting together, doing something together to benefit us and him in the future,” she explains.

Shortly after she arrived in the United States from Ecuador, she says, “I was at a job and I was pregnant and fired at four months, just because I was pregnant.” She has also “been through circumstances where I’ve had miscarriages, and not had enough time to take care of myself outside of work,” she says. When she suffered wage theft, Centro de Trabajadores Unidos en la Lucha (CTUL), a worker center, helped her navigate the situation. And now she is fighting as a member of CTUL for the Labor Standards Board, in hopes of winning more paid time off.

The Twin Cities are home to a broad coalition of unions, worker centers, and community groups, whose members lobbied, rallied, and presented petitions in favor of a Labor Standards Board. On January 25, Council Members Aisha Chughtai, Aurin Chowdhury, and Katie Cashman announced their intent to introduce the ordinance to the Minneapolis City Council.

The proposed Labor Standards Board would be appointed by the City Council and the mayor, and composed of 15 members: five representing workers, five the community, and five business. This Labor Standards Board would have the authority to create new, temporary boards to address labor standards in specific industries, like childcare or building management, as well as geographies, like downtown workers in low-wage industries, or a combination thereof. These boards would also be tripartite—composed of representatives of workers, the community, and business. While the temporary boards could not create laws themselves, they could make recommendations to the government, and such recommendations would be weighted heavily.

The idea guiding this legislation is that, to improve conditions in a sector, you need to study and review that sector, to learn about its specific challenges. How else would you know, for example, that employers in retail often change schedules at the last minute, upending workers’ lives, or that sexual harassment plagues the fast food industry?

Workers would have a voice in the process, and their participation would make industry boards more effective at improving conditions. If 150 workers were to sign a petition, this would require that the Labor Standards Board make a decision about whether to create a temporary board to investigate their industry. Alternately, members of the Labor Standards Board could simply decide to create a temporary board on their own, though they have to be somewhat discerning, as the ordinance limits them to two boards a year total.

Because both workers and business will have a seat at the table, the Labor Standards Board is a distant cousin of sectoral bargaining, but there is a key difference: The power to make changes and improve conditions lies with government, not with direct bargaining. (Minnesota’s nursing home board does have rule-making authority, similar to a public utility commission, though this power is somewhat circumscribed.)

Brian Elliott, the executive director of the SEIU Minnesota State Council, told me that the language for the ordinance should be made public in the coming weeks, and the City Council is expected to move forward on the Labor Standards Board soon after the election. The board has its opponents in business, particularly the restaurant industry. But, Elliott says, “We are hopeful it will pass in November.”

There are a number of ways, according to Elliott, that such a board could help address Tirado’s concerns about the lack of paid time off. It could recommend “implementation of minimum paid time off for workers, or time and a half for working on a holiday,” he says. It could also recommend automatic overtime pay for shifts that are 11 hours or less apart.

If history is any indicator, there is reason to be hopeful that they could bring real improvements. Worker boards have their origins in the Progressive Era, just before the New Deal period, when economic inequality was dramatic and rapid industrialization led to hazardous working conditions. Kate Andrias, professor at Columbia Law School, says workers and their advocates responded by organizing unions, pursuing state and local regulations, and experimenting with worker boards. The earliest boards in around 13 states were “designed to set wages and establish other labor standards for those workers, mainly women, without full citizenship rights or union representation,” Nelson Lichtenstein, labor history professor at UC Santa Barbara, wrote in January 2022.

Andrias told me, “They were trying to create new administrative structures that gave workers a voice and established working conditions on an industry-by-industry basis. This was not seen as in opposition or a replacement to unionization, but rather, a compliment. The idea was that workers should have independent organizations with which they bargain with employers, but also, there are lots of workers who don’t have such organizations, and democracy should have a mechanism to raise conditions for everyone in industry, and do so in a way that involves workers.”

During the pre-New-Deal era, the Supreme Court was hostile to labor protections, and routinely struck down pro-worker legislation. But then, the Fair Labor Standards Act, enacted in 1938, established committees of unions, business, and the public, with the authority to set industry-specific minimum wage standards. Designed to function together with the National Labor Relations Act, these committees brought results. “Seventy industry committees were established between 1938 and 1941, and their wage orders covered 21 million workers,” Andrias wrote in a spring 2019 article for Dissent. These early iterations of worker boards did not last forever; after around 10 years, this tripartite approach was abandoned, and the committees fell into disuse, writes Andrias.

Now, Minneapolis is poised to be part of a new generation of worker boards. Since 2018, three cities and six states have passed laws “enabling workers and employers to help set industry-wide standards,” according to a report by Aurelia Glass and David Madland, published in 2023 by the Center for American Progress. Many of these laws are tailored to specific industries: fast food workers in California, agricultural and direct-care workers in Colorado, nursing home workers in Michigan and Minnesota, farm workers in New York, home care workers in Nevada, and domestic workers in Philadelphia and Seattle.

But there are some examples of boards, like that proposed in Minneapolis, with broad mandates to address issues in multiple industries. In 2021, Detroit passed a law that allows a board to be established in any sector. And in 2023, California injected new funding into its Industrial Welfare Commission, in addition to the board focused on fast food workers.

Madland told Workday Magazine that workers have already seen gains from this youngest generation of boards. “The Minnesota board is in the process of raising wages for nursing home workers to a minimum of $20.50,” he told me over the phone. “Minnesota is also working on ensuring workers can take paid holidays. Home care workers in Nevada get $16 an hour because of the board. New York ensured that agricultural workers could receive overtime pay. The Seattle board is working on ensuring domestic workers have access to a portable paid leave system.”

Maryam is a worker at a daycare center in Minneapolis and a volunteer with ISAIAH, a faith-based group that organizes for economic and racial justice. She says the proposed Labor Standards Board “is very important to me.” Maryam, who asked that I only use her first name, works primarily with infants and toddlers. “I love working with them,” she says, but the pay is not high enough. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that “I tend to buy toys or gifts for the students, or help students who need support,” she says. “People who provide childcare do not get what they deserve.” (Elliott confirmed that recommending a higher wage for childcare workers is within the powers of the board.)

Tirado is highly motivated to make the Labor Standards Board a reality. “I’ve been out to marches when it’s time for us to march, been to hearings and listening sessions to be able to speak with council members, been there to do what I can when I can, because it really is in my interest that we have a table like this,” she said. “I might not be from this country, but as a worker, it’s something that’s a good opportunity for us and our kids.”

Tirado says being a part of CTUL has made her “a stronger woman. I’ve had to defend my rights at work. Sometimes we go through humiliation, from bosses or managers or coworkers or difficult situations. Before I would be more timid, fearful sometimes of saying things. By being a part of this organization and participating, I speak up more.” Her son chimes in: “I love CTUL,” he tells me, “because there’s toys.”

Tirado is six months pregnant, and her baby is due before Minnesota’s Paid Family and Medical Leave law goes into effect in 2026, so she won’t get paid leave to bond with her in those early months; once she exhausts her PTO, any leave will be on her own dime. As she gets ready to welcome a new baby, she yearns for more time to spend with her family, unencumbered by the stress of making ends meet.

“Our kids are innocent,” she says. “We’re not asking for something that isn’t fair or just.”