“Striking Maidens,” an article by Eva Gay, Eva Valesh’s pseudonym, in the St. Paul Daily Globe’s April 29, 1988 issue. Accessed with the Minnesota Historical Society’s Digital Newspaper Hub.

Share

This article is a joint publication with Minnesota Women’s Press for the December issue on Changemakers.

I have always struggled with the notion of objectivity in journalism. I believe many news outlets, whether they skew left or right on the political spectrum, often have another bias that has a major impact on how readers understand their reality: the bias of favoring business over labor.

Christopher Martin, author of No Longer Newsworthy: How the Mainstream Media Abandoned the Working Class, writes about the historic decline of labor journalism. The labor beat once had a large presence in newspapers. As the labor movement of the mid-20th century declined, the business model of traditional journalism became more commercial — advertising became focused on demographics rather than on circulation that attracts readers of all classes. Newspapers abandoned poor and working-class issues in favor of addressing more affluent and educated readers.

The labor press emerged to counter this trend. Workers and their organizations published news and literature with various political agendas. This provided a counternarrative to the corporate media machine. Minnesota has a rich history of female labor journalists and writers who were also advocates and activists. In the late 1800s, the Minneapolis Tribune and St. Paul Globe ran labor columns edited by Eva McDonald Valesh.

I stumbled upon Valesh’s biography the summer after I graduated journalism school. To me, she seemed like Minnesota’s Nellie Bly, having embedded herself in garment factories to report on working conditions in her twenties. Her journalism career was followed by public speaking and advocating for women’s labor organizing.

In Writing the Wrongs: Eva Valesh and the Rise of Labor Journalism, historian Elizabeth Faue examines how Valesh challenged gender norms in both journalism and the labor movement. She worked alongside women and girls and reported on the conditions and culture. Workers were inspired to participate in strikes after her reporting.

Valesh became a lecturer for the Knights of Labor and worked for the American Federation of Labor, organizing for different causes as her allegiances shifted. She was invited to public debates, where she was often the youngest, and argued for the importance of women’s organizing.

Faue writes that Valesh’s interpretations of working-class suffering showed an anti- immigration and anti-socialism bias in line with other labor voices at the time. She integrated the conservative gender ideology of some labor unions into her rhetoric. Many people attributed the social malaise of the time to men suffering from unemployment, and wanted women to organize so they could eventually “emancipate themselves from the industrial field back to the home,” leaving the role of breadwinner to men.

Although I differ from some of Valesh’s values and practices, I agree with Faue’s point that without the influential cultural work of reporters, investigators, and educators like Valesh, the labor movement would not have been as strong, its messages drowned out by a political landscape that was increasingly dominated by business interests. Faue examines how Valesh’s class mobility may have distanced her from working people, but her social ties with the upper classes served her organizing work, and showed a woman who transgressed the economic and gender norms of the time.

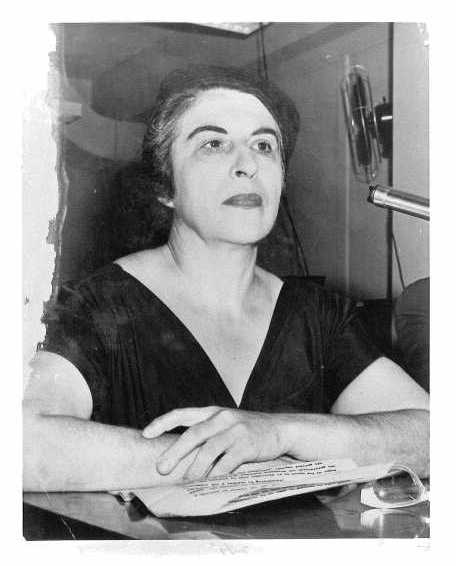

I also revisited the work of Marvel Cooke, who was born in Mankato in 1903 and was the first African American woman to work for a white-owned newspaper. She was a radical community and union organizer who inspired Black activists and scholars like Dr. Angela Davis. She worked in various industries and reported on the exploitation of Black domestic workers in white homes, which led to regulation in the industry. She was mentored by W.E.B. Du Bois, and helped found a chapter of the Newspaper Guild in New York, one of the first labor unions organized by journalists. She was later investigated by Senator Joseph McCarthy for her affiliation with the Communist Party.

McCarthy also investigated Irene Paull, a radical political activist from a Jewish immigrant family in Duluth. Paull edited The Timber Worker during the timber worker strikes of 1937. The paper later became the Congress of Industrial Organization’s official newspaper: Midwest Labor. Paull supported the Farmer-Labor movement, the most successful third-party movement in the U.S., uniting rural farmers with urban laborers. Other women writers and organizers helped lead this movement, including Susie Stageberg, the “mother” of the Farmer-Labor party, who edited The Organized Farmer in Red Wing. Also from Duluth was Sabrie Akin, who, in her twenties, founded the Labor World newspaper, edited by Catherine Conlan today.

A short walk from the University of Minnesota’s West Bank campus is a building named after Meridel Le Seuer, a writer and teacher who covered the lives of working people in the Midwest for the Communist Party’s Daily Worker. She wrote fiction and authored a manual on creative writing, Worker Writers, for the Works Progress Administration.

I’m still learning about the writers I’ve mentioned here, many of whom are left out of the usual lists of pioneering journalists and women. Graduating with a journalism degree when there is so much distrust — of the media, of our neighbors, and of our leaders — I’ve often doubted what my gifts and perspectives as a young woman can bring to my community and the field of journalism. Learning about these writers and editors who were influenced by working people and had an influence on the conditions of their times; who were complicated, radical, and courageous, and fought against the narratives upholding oppression and exploitation; shows me there is room and need for my own voice.