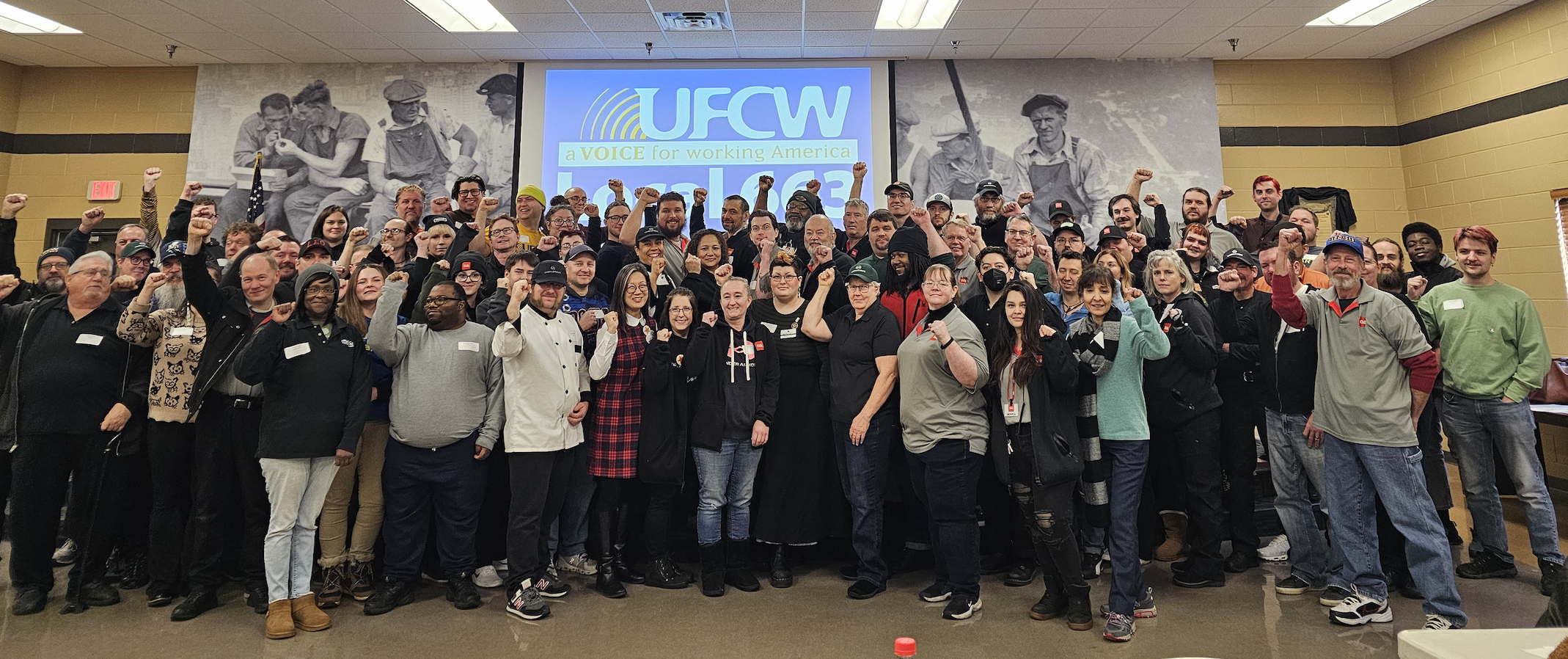

2025 UFCW Local 663 Twin Cities Grocery Bargaining Committee. (Photo: Jessica Hayssen, UFCW 663)

Share

Monica Duque never knows how many hours she is going to get in a given week. She works at the Jerry’s Cub Foods on East Lake Street at the front of the store, helping customers, overseeing cashiering, and running online shopping. She finds out her hours, she explains, “when the schedule is posted on Friday, for the week after next.”

“There is no consistency,” says the 24 year old, which makes it hard to save money, or plan much for the future. She makes a little over $20 an hour, and even being cut 10 hours in a week can have a big impact on her finances. “I can do morning one day then night shift the next day. I go from eight-hour days to barely getting seven-hour days. I can never really rely on how much money I’m going to make.”

“People just want to be able to afford to live. One job should be enough to do that.”

Duque is one of around 9,000 Minnesota grocery workers whose union contracts with 14 different companies expired in early March. Of these workers, the vast majority are engaged in coordinated bargaining with seven employers: Haug’s Cub Foods, Jerry’s Cub Foods/Jerry’s Foods, Kowalski’s Markets, Radermacher’s Cub Foods, Lunds & Byerlys, Knowlan’s Festival Foods, and UNFI Cub Foods.

Monica Duque (Photo: Jessica Hayssen, UFCW 663)

At least the bargaining is coordinated on the part of their union, United Food and Commercial Workers Union (UFCW) Local 663. The union sits down at the table with the employers together, and gives them joint proposals, but the employers are insisting on bargaining seven different agreements.

“The employer does not want to do coordinated bargaining. They think it’s better to do it all separately,” UFCW 663 President Rena Wong told me over Zoom after one such bargaining session on February 25 at the Minneapolis Federation of Teachers building. Behind her sat 65 members of the bargaining committee, listening to our interview.

Wong explained that workers, nonetheless, are hoping to band together to rectify the poor pay and that workers like Duque are facing. “Both the hourly wage and the guaranteed number of hours that we actually get scheduled are both tied and dependent on each other for us to be able to make enough to take care of ourselves and our families,” she said.

There are signs that the skeleton crews are also souring the shopping experience for customers. UFCW Local 663 ran an online survey of more than 500 customers of Minnesota Cub Foods, owned by United Natural Foods Incorporated (UNFI), from January 27 to March 3. They found that customers want to see more staffing in stores, with 84% saying they’ve noticed “negative” changes to staffing. According to the union, concerns about staffing ranked even more highly than worries about food prices.

“Over the last 12 months, UNFI has severely cut labor hours in stores, and implemented radical changes to the scheduling of its employees,” the union said in a statement accompanying the survey findings.

According to Wong, there are a number of other priorities workers are fighting for. They don’t want the company to have the power to transfer workers to other stores whenever they want, they want secure retirement, and they want improvements to their health coverage (all of the eligible workers who are part of coordinated bargaining are on the same health fund). “Folks want more of their dental covered,” Wong says. “They want a little bit more of their vision covered. They want their out-of-pocket max and deductible to go down a little bit.”

Michael Butler has been working at the Lunds & Byerlys at the Plymouth location since January of 2007, all except for a year. He is an assistant manager for the deli, which means “I manage and run the entire deli department in the store, everything from the sales floor to employees underneath me, ordering, receiving, and paying bills, talking to vendors, looking over expense reports,” he explains over the phone.

His biggest issue is employees’ health fund, he says, and he has been “seeing red flags pop up in negotiations this time. They are wanting to cut the amount they are putting into the fund and the amount that’s in the fund and have employees bear more of the cost.”

This is a concern for him, as he is the only paid person in his household. “My wife is stay-at-home, and we’re starting to try for a family of our own,” he said. “We rely on having good, affordable healthcare where we know coverage is going to be there for us.”

The coordinated negotiations with seven employers is ongoing, and UFCW 663 is doing open bargaining, issuing broad appeals to the membership to show up for sessions. In addition to this coordinated process, there are hundreds of other UFCW 663 members who have expired contracts with smaller employers. It’s often the case that those employers will wait and see how coordinated bargaining goes.

When I asked Wong if a strike is a possibility, she told me, “We don’t want to strike. Like, if you ever ask a worker, ‘Do you want to strike?’ people will tell you no, right? But will we let the employers try to defund and collapse our health and welfare plan? No. Will we let employers try to drag out how long it takes to fund our pension so that it might actually become insolvent? No. And then are we going to accept 45 and 50 cent increases for our part-time members who already work two and three jobs as is? No.”

She added, “We’re going to do what we’re going to need to do to be able to, to pay our bills and take care of our families.”

Duque, whose store is part of the coordinated bargaining, started at her job three years ago. At first she worked in the deli, then she was moved to grocery, before being switched to the front of the store where she is now. “I’ve been trying to get paid more for the extra responsibilities I’ve taken up,” she says. “Ever since running online shopping and learning to manage cashiers, I haven’t received any more monetary compensation for volunteering for those tasks.”

For her coworkers, unpredictable schedules can create considerable hardship. “Whenever people get days cut out of their schedules, they say they’re worried about how they can pay for their bills or food with bills going up. They have to plan on getting childcare, because not having consistent hours means they have to get someone to watch their kids.”

Duque says she is “grateful” that she is not in the position of being unable to pay her bills, but her unpredictable hours do make it hard to feel a long-term sense of security. “I’ve barely even thought about if I could buy a house, as there is no hope on the horizon to make more. I can’t get it in my hours and can’t get it in my wage no matter how many more tasks I take up.”