Share

Claire (whose name has been changed for anonymity) has been donating plasma twice a week for three years. “My husband and I lost our cleaning-service business three years ago,” the fifty-six-year-old said outside of her local BioLife plasma collection center. “The money doesn’t cover the whole month, but we need it for extra things in the budget.” These extra things consist of her daughter’s softball fee and money towards a vacation.

Claire is far from the only person who is donating her plasma because she is stretched for cash. In fact, it seems the majority of people that we spoke with outside of the collection center donate plasma for the financial compensation.

Cody is a twenty-five-year-old who works jobs in construction and sales while also studying at Anoka Technical College. “I’ll do anything to make money as long as it’s legal,” Cody said outside of BioLife in Maple Grove. Similar to Claire, he has been donating plasma twice a week for three years.

While somewhat altruistic, plasma donations supply a multibillion dollar industry that is structurally designed to take advantage of stagnant wages and income disparity many of the poorest workers in the country endure.

While unemployment remains at historically low levels, wages have continued to stagnate. From May 2017 to May 2018 real average hourly earnings remained largely unchanged, increasing by 0.3 percent over that one year period. The nominal increase is largely attributed to people working longer hours.

Along with stagnant wages, income disparity is increasing. According to a report done by Congressman Keith Ellison and his staff the average CEO to median worker pay ratio among the first 225 Fortune 500 companies is 339:1.

This disparity coincides with the growth of the plasma industry. Looking at plasma centers offers a window into how the working poor are struggling to survive amid their pronounced economic struggle in the United States, while plasma protein corporations are profiting from desperation and misfortune.

The 5-billion-dollar global plasma protein therapeutic industry is expected to exceed 31 billion dollars by 2024 due to the growing amount of plasma-based medicines, along with the increased prevalence of over two hundred life-threatening diseases including hepatitis A&B, tetanus, and even rabies, according a market analysis done by Grand View Research. In addition to the increased demand of these medicines, commercial plasma protein therapeutic corporations are receiving a stark increase in supply.

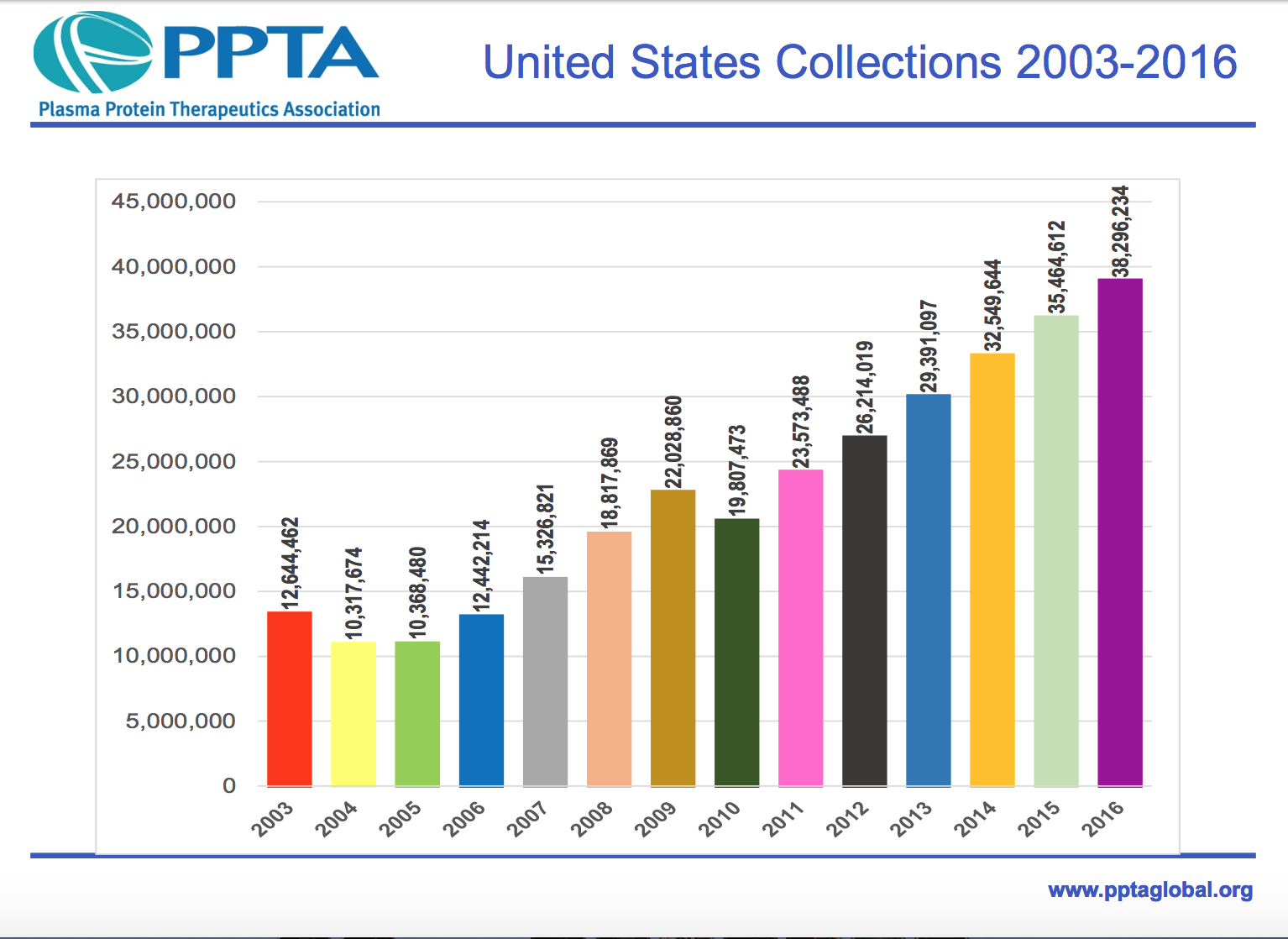

More and more Americans are beginning to donate plasma for money to cover their everyday expenses. In 2016, private collection centers across the United States gathered nearly 40 million collections; the highest it’s ever been. Since 2005, the number of donations has nearly tripled.

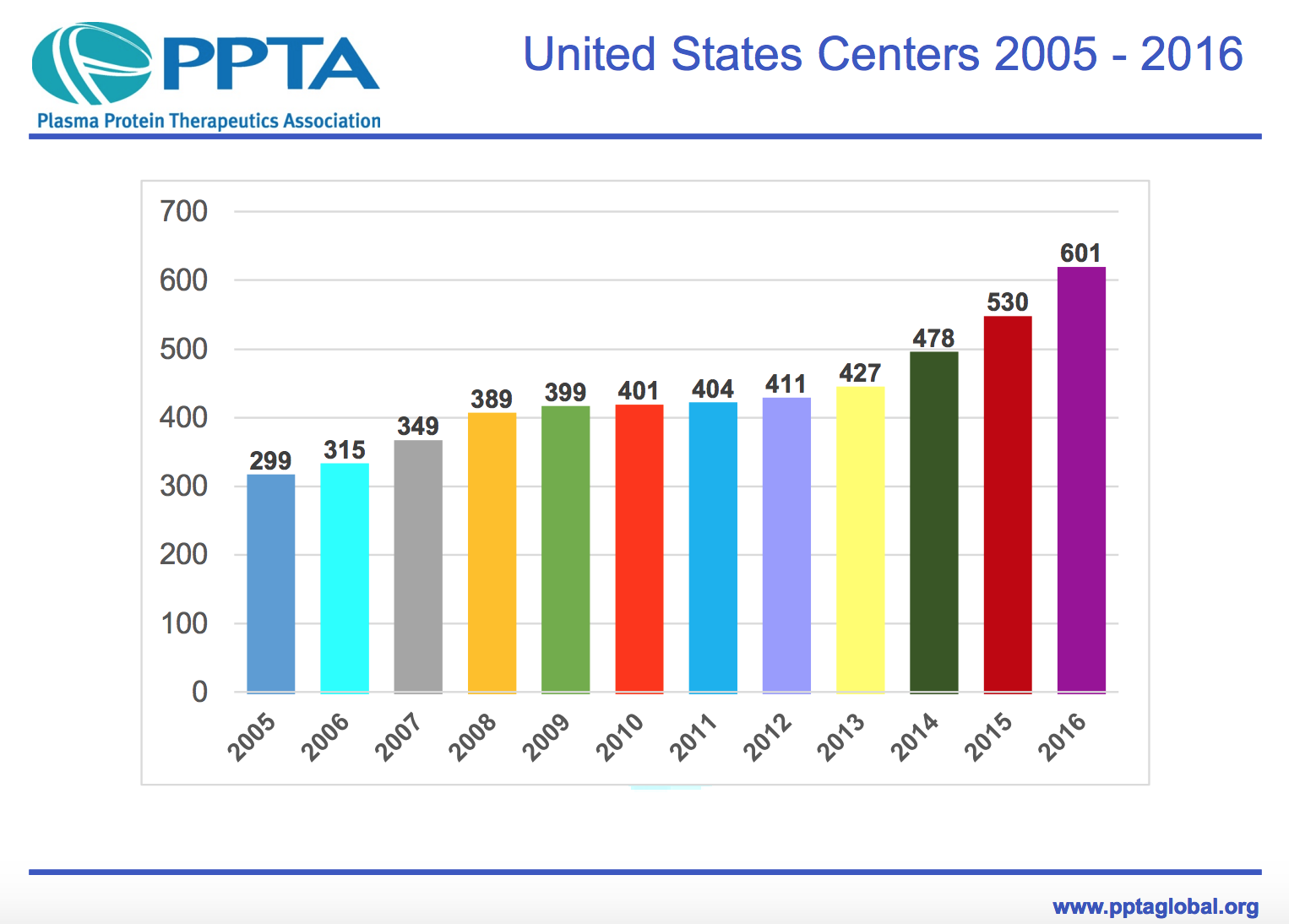

There are 601 plasma donation centers in the United States and 80 percent of these are located in America’s poorer neighborhoods, according to a report by ABC. Since 2005, the number of donation centers hasmore than doubled.

The industry is one that helps millions of people worldwide, but it seems to also be one that relies on cash-hungry people to thrive. Between the years of 2006-2008, there was a 43 percent increase in the number of donations in the United States; the highest increase in a three-year span. In that time, Americans went through the most financially unstable period since the Great Depression.

Plasma donation centers, like BioLife or CSL, are run by private, for-profit corporations which produce plasma protein therapies (PPTs). PPTs are a group of essential medicines extracted from human plasma through processes of fractionation. They are used to treat a number of rare, chronic diseases resulting from inherited or acquired protein deficiencies. Examples of these diseases include hemophilia A and B and immunodeficiencies. PPTs are also used to treat critical burns, severe blood loss and sepsis. The manufacturing of PPTs requires considerable amounts human plasma.

Plasma is the fluid part of the blood and is harvested by donors through a process called plasmapheresis. A needle goes into the donor’s arm and blood pumps from his or her vein into a device that separates plasma from the blood cells. The plasma is stored, and the blood cells return back into the body, usually accompanied by saline. This process yields noticeably higher volumes of plasma compared to the other method of separating plasma from whole-blood donations; a method commonly used by nonprofits such as the American Red Cross. Plasmapheresis also allows donors to donate more frequently and in larger quantities.

The United States is one of few Western countries that permits biweekly donations and donor compensation. Canada and some European countries have taken a “better safe than sorry” approach for the amount of donations, allowing people to donate once every 28 days in some cases. This has caused the United States to monopolize the business, providing 94 percent of plasma used around the world, according to an ABC News report. Given the amount of plasma supplied by the commercial sector and the inefficiency of deriving plasma from non-profit, whole blood donations, it is unsurprising the world’s supply of plasma relies on commercial companies such as a CSL Behring, Baxter International, Grifols, Shire, and Octapharma.

The threshold to become a donor is low, attracting many people. There are only a few requirements to become a donor; you must be 18-years-old, weigh at least 110 pounds, pass some medical examinations, have identification and proof of residence. The process takes no more than an hour and a half in most cases and is relatively pain-free. For the working poor in need of cash, the weekly, non-taxed compensation received from two hours of “work” is a bargain. “Where are you going to get a part-time job that can pay that kind of money,” said Mike, a 57-year-old who uses the money he gets from donating plasma to fund his vacations. Mike said he was skeptical at first about giving plasma for money, but, after his first donation two years ago, he’s been making biweekly trips to BioLife Plasma Services in Maple Grove.

The plasma protein therapeutic industry booms while working conditions and wages of America’s poor and average laborers remain substandard. Therefore the plasma industry functions as an indicator of the quality of jobs available in the economy. The success of the industry indicates that more people are being treated for life-threatening diseases, in turn saving millions of lives. But, the correlation between struggling Americans and the industry’s increasing profits is undeniable.