Share

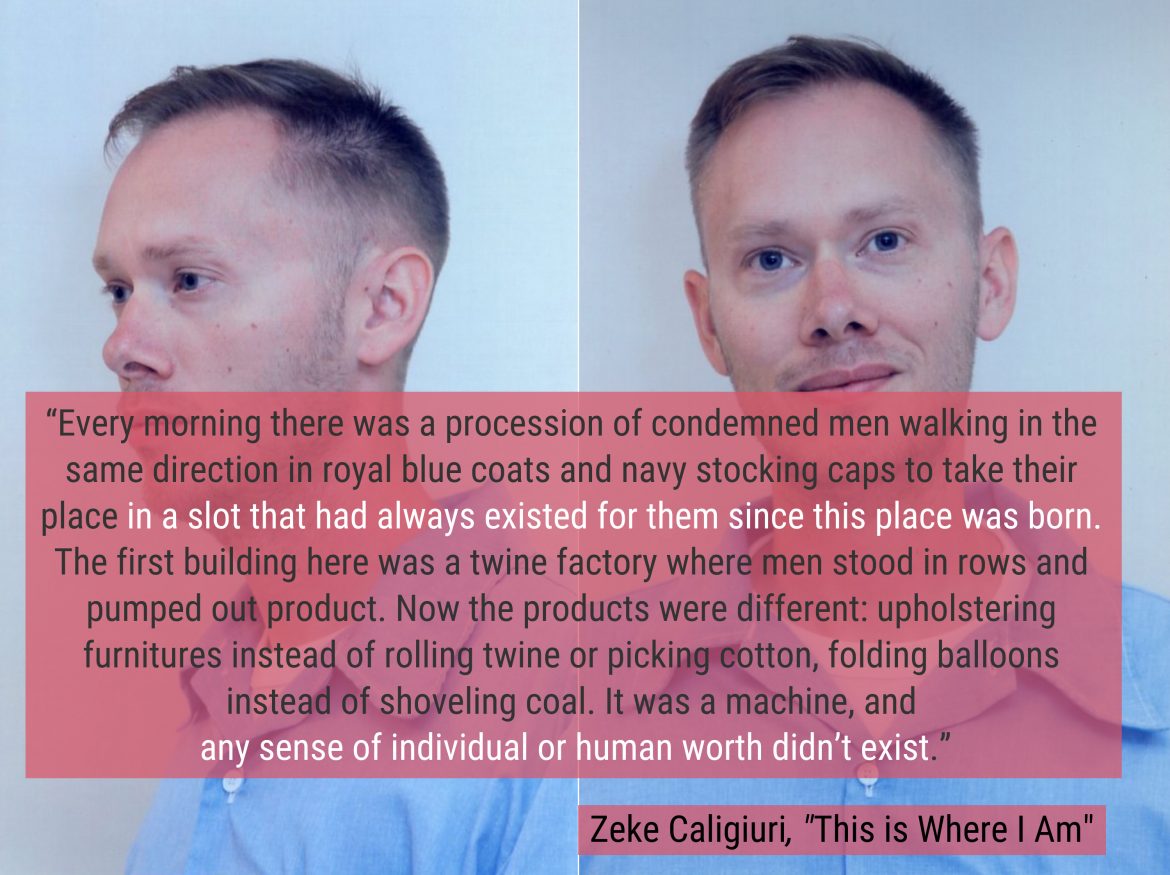

Ezekiel “Zeke” Caligiuri remembers learning that inmate labor built St. Cloud Correctional Facility. Upon that discovery, he began seeing the walls of his cell in a different hue. Zeke observed that he “lived in a space that had been lived in for 100 years.” He grappled with the sobering reality that countless men before him had labored to sustain their own confinement and would continue to do so long after he was gone.

As Zeke describes in his memoir, “I thought about a world that had no problem forgetting any of us ever existed.” Being forgotten behind concrete and steel bars also means that there is little observance and awareness of the treatment of prison laborers like Zeke.

Balloons, fleece pants, office furniture, docks, and laundry services are among the commodities and services provided and manufactured in Minnesota Prisons through MINNCOR, a profit-generating entity within the Department of Corrections (DOC). MINNCOR has its own infrastructure and staff, including a CEO. MINNCOR operations have expanded to almost $50 million in sales revenue alone.

Separately, the DOC coordinates minimum security work crews that labor throughout the state on small manual projects such as cleaning dog parks in Eden Prairie or building low income homes in greater Minnesota.

In an interview with DOC Deputy Commissioner Ron Solheid and District Supervisor Terry Byrne, they explained that the precursor to the “sentence-to-serve” work programs was “designed around a restorative justice model in 1987. Really, the state’s interest was, well, if we can fund some of this, it gives county jail inmates something to do, something positive that’s productive. It repays the community.”

Public records indicate that MINNCOR executives make over $100,000 a year. For example, MINNCOR CEO David Milton made $138,061.92 in 2017. Due to a legislative mandate, for MINNCOR to be self-sufficient, they must sell inmate labor contracts to private companies, government entities, and nonprofits.

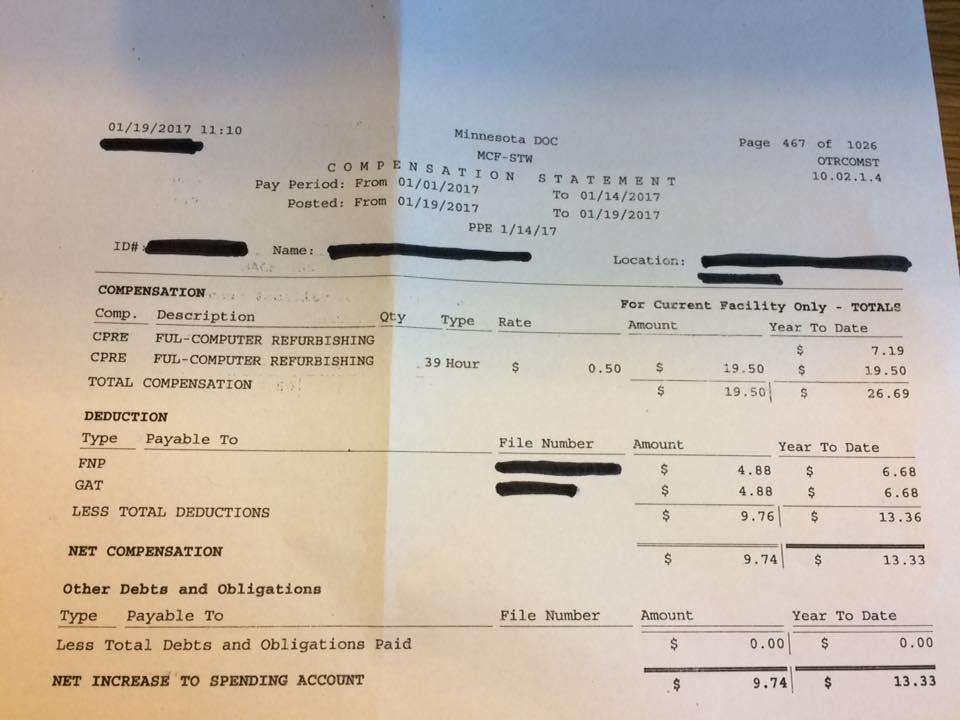

MINNCOR laborers and DOC work crews earn on average less than $1 an hour. Pay ranges from 25 cents to $2 an hour.

The highest paying positions are assigned under strict circumstances, out of reach for the vast majority of inmates. According to DOC Directive 204.010,

“No more than 20 percent of the offenders may advance through step six (pre-advanced) and no more than 10 percent of the offenders may advance through step eight (advanced).” Increasing wages are not a possibility according to Solheid. “If we tried to change rates to pay the participants higher wages, I don’t know that we would have much of a market for MINNCOR products and DOC services.”

If an inmate commits an infraction or switches facilities or jobs, they start back at 25 cents no matter how many years in custody or time in a prior appointment.

Extracting Revenue through Deductions and Canteen

An inmate and award-winning investigative journalist for The Prison Mirror, the Minnesota Stillwater Correctional Facility’s newspaper, Matt Gretz showed that by the late 1980s the typical inmate could make $2 an hour compared to the US minimum wage of $3.35 an hour. According to Gretz’s reporting, the plan ushered in the modern era of inmate pay. Over time, many jobs saw starting hourly pay slashed from $1.50 to 40 cents. At the end of the decade, pay further declined from 40 to 25 cents.

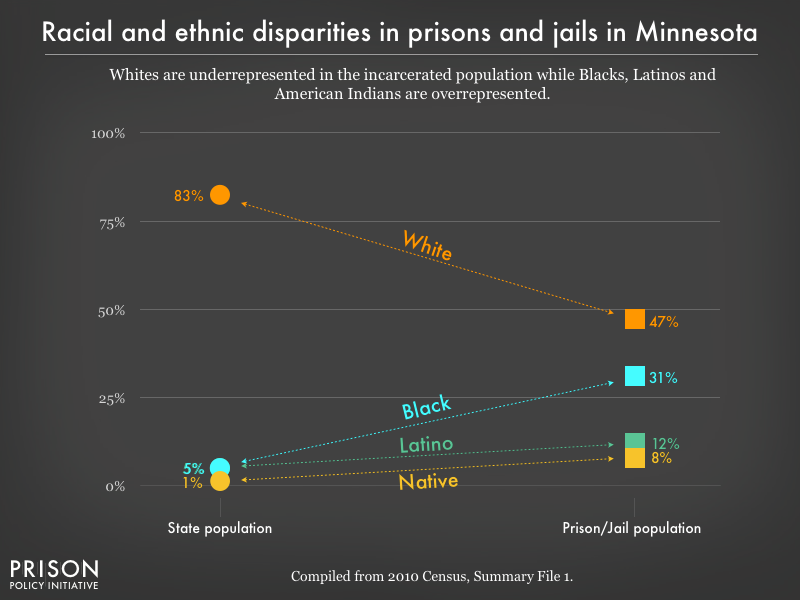

Decreasing wages coincided with 1990s “tough on crime” laws that exponentially increased incarceration rates for Black men. Furthermore, Minnesota holds the distinction of having one of the highest incarceration rates for Native Americans in the United States. According to DOC data

, the majority prison population consists of people of color in a state whose population is 90 percent white. (The DOC labels “Hispanics” as “White.”)

According to Gretz’s reporting the low wages of the current system were codified under the 1993 Unified Pay Plan. DOC officials argue that the Unified Pay Plan has been misunderstood. Regarding declining wages, Solheid explained, “I wouldn’t say it dropped, it more equalized.” He further explained that work programs are, “a good deal, since the DOC supplies the gear, training, bed, transport, and healthcare.” Consolidation in wages also paralleled the 1994 consolidation of formerly disparate prison industries into MINNCOR. The formation of MINNCOR corresponded to a broader push to offer products to private markets.

Solheid commented that, “It’s unfortunate in that a lot of folks feel like prison labor is slave labor. Frankly all these programs…it’s voluntary. You are not compelled, you don’t have to participate. A lot of folks that do participate get a lot out of it.

“Ultimately, the individuals on our work crews in most cases are saving money. Because if you are working 40 hours a week at a buck and a half an hour you are getting what, $60 a week? Food, clothing, shelter, medical care is all provided. Transportation to and from the job is all provided. They aren’t buying tools, equipment, safety clothing. That’s all paid for by the program. So that’s kind of that balancing, how do we make this self sustaining and self-supporting. It’s not using taxpayer dollars, it’s using dollars from, in a sense, the cities or whatever, you know, but they are getting a lot of value back,” Solheid said.

However, inmates do pay into some of the services Solheid described, leading to substantially lower take home pay. The categories from which the DOC deducts pay include: court-ordered restitution, cost of confinement, facility obligations and unpaid medical co-payments, federal and state filing fees, court-ordered fines, and disciplinary restitution.

According MINNCOR internal data from July 1 to Sept. 30, 2016, inmate wages were reduced by 77 percent through these kinds of deductions, approximately half of which went to “cost of confinement.” These reductions mean that inmates are legally obligated to pay for the conditions that facilitate their own exploitation. Additionally, prisons reduce expenses substantially by using inmate labor to serve food and maintain equipment.

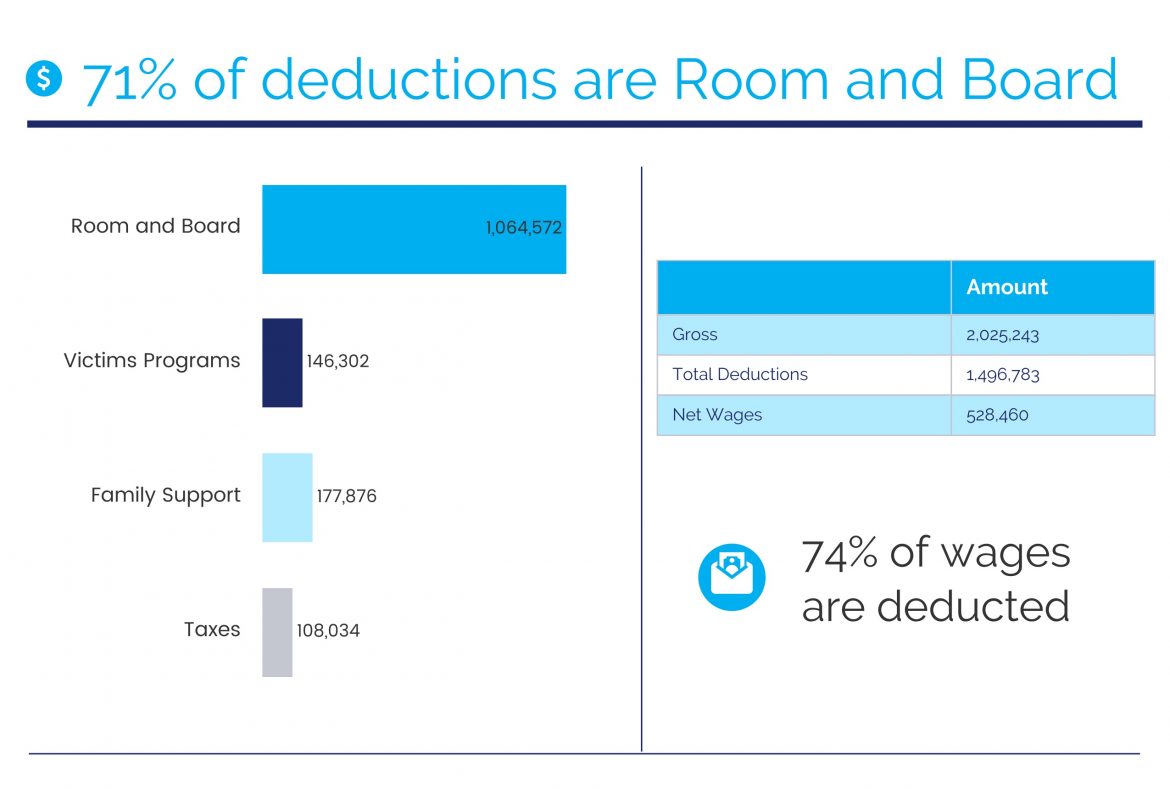

Those that are assigned to work for companies that engage in interstate commerce are obliged by federal law to be paid prevailing wages. However, up to 80 percent of their wages can be deducted through the same levies, dramatically reducing net pay. The Federal Prison Industry Enhancement Certificate Program oversees rules of interstate commerce and is set up “to permit the use of the room and board deduction to lower costs otherwise incurred by the public for inmate incarceration.”

According to the Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program statistics for the quarter ending September 30th, 2017, 74 percent of wages are devoted to deductions, over half of which are for room and board.

Based in Eden Prairie, global balloon supplier Anagram holds the largest prison labor contract for a private entity in the state. In fiscal year 2016, Anagram held a contract worth slightly over $9 million, which is almost 19 percent of total revenue for MINNCOR. Solheid and Byrne argue that balloon packaging positions are beneficial because they offer “real life work experience; you have to be there on time.”

This dynamic is compounded since inmates have no legal ability to challenge their exploitation. Lawsuits have challenged prison labor by arguing that the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) applies to inmates. In 1938, the FLSA passed as part of sweeping legislation designed to guard against unfettered labor abuses. The bill set national minimum wage standards and, most notably, banned child labor.

A 1994 Minnesota District Court case, McMaster v. State of Minn, ruled that work is a condition of incarceration, making a distinction between convict laborers and workers. Therefore, inmates are not entitled to federal and state labor protections. Failed legal challenges indicate that the DOC operates with near impunity. With men of color constituting the majority of prison laborers, the prison industrial system is racialized. Systemic inequities are undoubtedly part of the fabric of prison labor in the United States, with their own particularities found in Minnesota.

MINNCOR

In 1996 the Minnesota Legislature directed MINNCOR to devise a business plan. According to a report from the legislative auditor’s office, “The Legislature never privatized MINNCOR, but the message was clear: operate without a state subsidy. The department revised its five-year plan in 1997 with a major goal that MINNCOR achieve self-sufficiency by fiscal year 2003.”

MINNCOR was under greater pressure to reduce costs and shift institutional inertia decisively towards profit. The first impacted revenue generator was the canteen system. MINNCOR manages the prison canteen system—the internal grocery and convenience store for inmates. In 2003, the state’s disparate canteen systems were consolidated under MINNCOR. The expectation from inmates was that bulk purchases would cause prices to drop. Instead, canteen prices increased.

2003 was also the first fiscal year that MINNCOR was profitable. Annual profits for 2003 totaled $100,000, jumping to $2.5 million in 2004. Centralization allowed the state to more easily dip into MINNCOR profits as budget cuts abounded—putting yet more pressure on MINNCOR to generate profit. According to annual reports, in 2008, canteen sales were 18 percent of MINNCOR’s revenue. By 2014, canteen sales amounted to $10.9 million, almost 25 percent of overall sales revenue for MINNCOR. This means that the largest portion of money that MINNCOR generates comes from their internal monopoly over products sold to inmates.

The DOC also has a monopoly over the bodies of incarcerated men. Despite claims that prison work is voluntary, this authority is wielded to compel men to work for low wages within numerous industries reproducing conditions that manufacture a cheap labor supply.

Amid discussions of low wage labor, prison laborers themselves are often overlooked. The Department of Corrections conceals the ubiquitous nature of what inmates produce and contribute to society, thereby making their daily presence invisible, hidden in plain sight.

Envisioning The Future for Prison Laborers and Formerly Incarcerated

Natrina Gandana, Program Director of the Northern California nonprofit The Last Mile (TLM) explains that their program is rooted in the philosophy that, “If you give them [inmates] more, they will respond… If you keep the bar low, you don’t get the full potential.”

In 2016 TLM rolled out TLM Works, a web development startup inside San Quentin State Prison. TLM Works pays a minimum of $16.79 an hour. Revenue generated from the development project goes back into the nonprofit, serving as a self-sustaining resource.

NPR reports that in Indianapolis a group of female inmates took advantage of a volunteer prisoner higher education program to develop a program for women to rebuild abandoned homes. Women would then be allowed to live in these homes after completing 5,000 hours of sweat equity. “This would also help solve a second intractable social problem: the lack of housing for ex-offenders, which had helped send so many women she knew back to jail.” The women were able to successfully lobby the legislature to pass the Constructing Our Future bill. “The women at Indiana Women’s Prison hope their new re-entry program can be a concrete and inexpensive national model for providing ex-offenders with both housing and a marketable skill.”

In a 2018 Ted Talk, Deanna Van Buren explores a world without prison. Van Buren has leveraged her architecture background to design restorative justice centers. Her planned initiative, “will be the country’s first center for restorative justice and restorative economics.”

Under construction in East Oakland, Restore Oakland will be a comprehensive center. “These are spaces that address the root causes of mass incarceration, and not a single one of them is a jail or prison,” Van Buren said.