About 4,000 janitors across the Twin Cities, members of SEIU Local 26, went on a 24-hour strike over unfair labor practices last week.

Share

Some 4,000 Twin Cities janitors walked off the job Feb. 27 for higher wages, paid sick days and other demands.

HealthPartners brought 1,800 nurses, technicians and other caregivers at its metro-area clinics to the brink of a strike before reaching a last-minute deal.

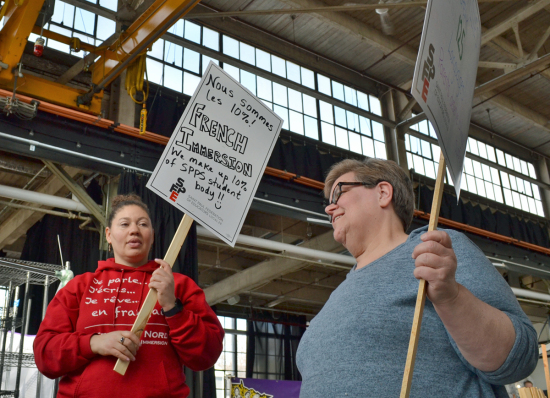

And next Tuesday, 3,600 union educators, frustrated by the district’s refusal to consider their student-centered contract proposals, could go on strike in St. Paul.

Strikes have been in the news a lot here lately, but it’s not just a local phenomenon.

According to labor market statistics released by the federal government last month, the number of U.S. workers who participated in major strikes surged in 2018 and 2019.

On average over those two years, 455,500 workers joined major strikes or work stoppages involving 1,000 or more people. That’s the highest two-year average in 35 years, and more than the total number of striking workers in the previous six years combined.

The numbers suggest that, despite low unemployment and steady economic growth, the U.S. economy isn’t as great as some would claim, particularly not for working people.

AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka, the nation’s highest-ranking labor leader, said the strike surge reflects a “sea change” taking place nationwide.

“Working people, completely fed up with an economic and political system that does not work for us, are turning to each other and using every tool at our disposal to win a better deal,” Trumka said. “Because of the courage of every worker who said enough is enough, we all stand on a stronger foundation today. Solidarity works. And we’re just getting started.”

Despite healthy corporate profits, wage growth has been slow since the economy emerged from the Great Recession. The 2017 tax cut, which President Trump promised would raise average household wages by $4,000, has overwhelmingly benefited corporations and the wealthy instead.

Executive pay, meanwhile, continues to outpace the wages of average working people. In 2018, CEOs at the largest publicly traded companies earned, on average, 287 times more than the median employee.

Historically, worker frustration has boiled over onto the picket line when working people feel they have leverage, said historian Peter Rachleff, co-director of the East Side Freedom Library in St. Paul.

The low unemployment rate likely has emboldened people to stand up for themselves and risk employer retaliation, knowing they can easily find another job. Frustration, meanwhile, has been building for decades, as gains in productivity have failed to trickle down into workers’ paychecks.

“Much of this productivity growth has also emanated from a growing intensification of work, which has made life on the job harder and more stressful,” Rachleff said. “So workers are not only generating more wealth, which is being captured by their employers, but they are also just plain working harder.”