Share

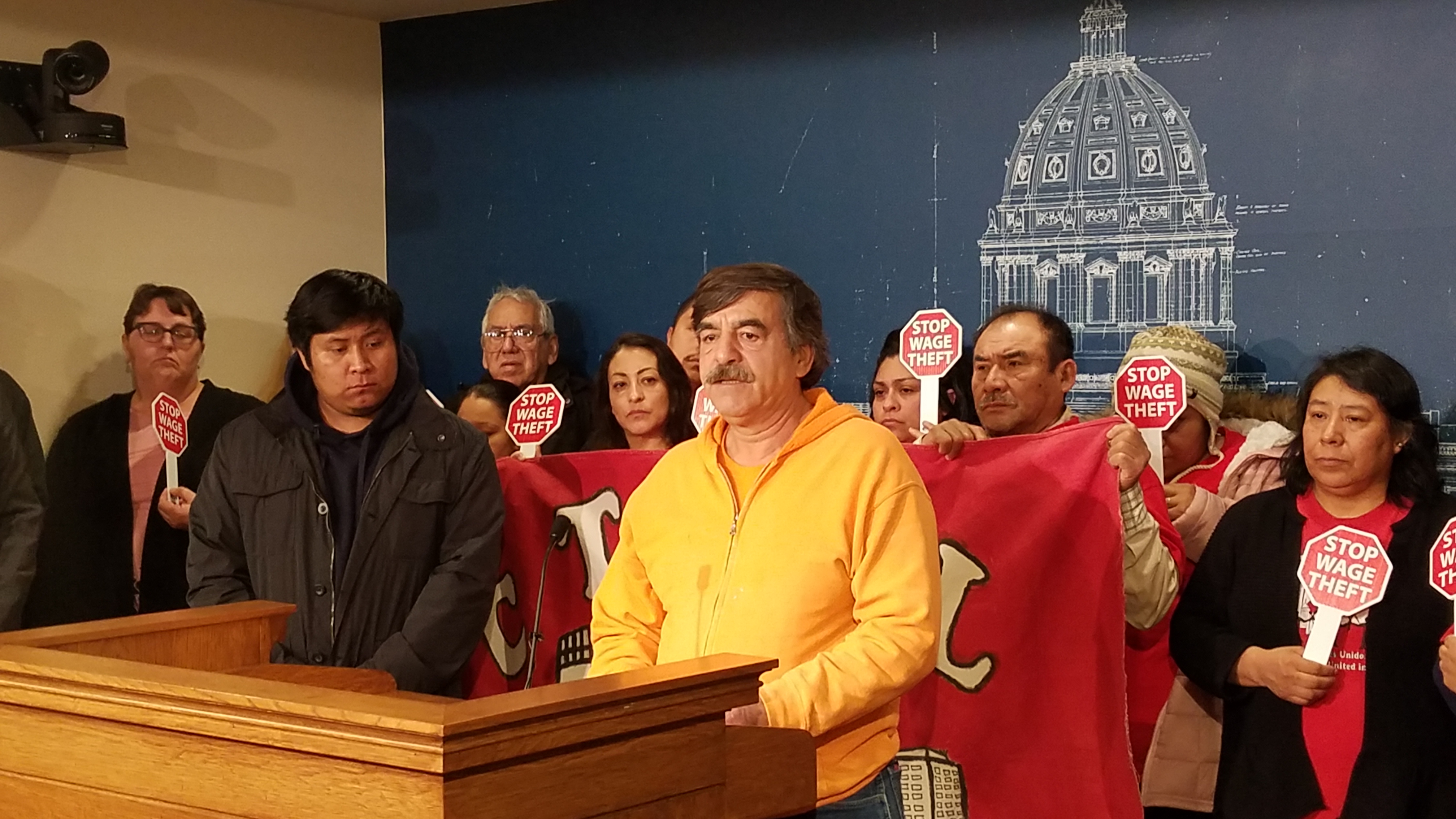

Workers and business owners highlighted the need for stronger wage theft laws during a press conference and legislative hearing at the Minnesota Capitol on February 6. The hearing before the Minnesota House Labor Committee was the first stop for HF6, a bipartisan bill that would set rules and penalties for employers who avoid paying, or fail to pay, wages earned by their employees.

“I am here today to demand an end to this practice of wage theft,” said Humberto Miceli, a member of Centro de Trabajadores Unidos en la Lucha (CTUL). With the help of CTUL, Miceli was able to recover wages stolen by an employer, but in the end he received only 10% of what he was owed. “It is real people who suffer the consequences the way things are right now,” added Miceli.

Cecilia Guzman, also a member of CTUL, told the committee she was owed two thousand dollars by a cleaning company in 2014. The court ordered them to pay but, “the person still hasn’t paid me to this date,” she said.

“Fourteen of my 20 paychecks, including my last one, have been shorted,” said Allegra Bipes, a security officer at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD). “On some, I was not paid for all of my hours worked, or I was not paid for overtime hours. On others, I was not paid my shift differential or for holidays. This is wage theft,” she continued. “For people like me, who live paycheck to paycheck, I need to be paid all that I have earned, on time.”

Based on complaints filed with the Minnesota Department of Labor and Industry (MNDLI), an estimated 39,000 Minnesota workers are not paid what is owed to them in earned wages each year. In 2015, the last year data was compiled, the Department recovered $1.3 million in back wages for Minnesota workers. MNDLI, as well as labor and community organizations, maintain the scope of the problem is much larger since most workers don’t report wage theft violations, many out of fear of retaliation from their employer.

“There are no repercussions for some of the worst offenses that we see in the construction industry and I am here today hoping legislators support HF6,” said Arturo Hernandez, a journeyman carpenter with Carpenters Local 68. “If I stole money from my boss at work, I would go to prison.”

Wage theft as a way of doing business

Wage theft crosses the boundaries of income, race and gender, but the incidence of violations is higher among low-wage workers and people of color and more prevalent in certain industries. A 2016 survey of 173 low-wage workers in the Twin Cities conducted by CTUL found that half of the workers had faced wage theft in their workplace. Sixty-six percent of respondents from the janitorial industry experienced wage theft. The Minnesota Coalition to End Wage Theft has found that residential construction, building and other services, security, agriculture and the hospitality/restaurant industry are all areas where wage theft is a common practice.

“In my time in the restaurant industry, I’ve seen wage theft as the norm, not the exception,” stated Kevin Osborn in testimony before the committee. Osborn is a line cook in Minneapolis and member of the Restaurant Opportunities Center (ROC-MN). Osborn said it is standard procedure for cooks to set up their workstations before punching in and continue cleaning them after punching out. Sometimes employers will move hours around between pay periods to avoid paying overtime, he said; other times they don’t bother paying at all. And if a worker complains? “We don’t call it retaliation,” Osborn said. “We call it getting your hours cut.”

Wage theft happens in many ways and for many reasons, but for some employers in certain areas of the economy, wage theft is a deliberate model for exploiting workers and extracting extra profit.

Burt Johnson, general counsel for the North Central States Regional Council of Carpenters, has first-hand knowledge that wage theft is a calculated way of doing business in certain industries. Johnson uses the term “payroll fraud” to name the systematic, planned theft of wages and says it is “the predominant business model in the residential construction market in Minnesota.” Residential construction includes building and renovating single family homes as well as apartment buildings, housing developments and assisted living/senior housing projects.

In a 2016 interview, Johnson estimated that “it’s possibly over 50 percent of the market,” adding that, “it’s hard to say exactly what the impact of payroll fraud would be on the construction industry, on the economy of the state of Minnesota, but it’s no doubt in the tens of millions of dollars, likely over $100 million.”

At the hearing, Carla Arceo, owner of the Minnesota-based construction company Frida Drywall, explained how competition with contractors that commit wage theft is hurting her business.

“I employ over 50 employees who make a strong middle-class wage and good benefits,” Arceo said. “Frida Drywall has been following the rules but it is not fair that other subcontractors who are not paying taxes, workers compensation, employee’s benefits, can take advantage of our industry, winning jobs with low prices because they pay very low rates to employees and they pay in cash. I’m here representing all the loyal companies and business owners who are looking for positive change.”

“Good employers are getting burned by these criminals – and that’s what they are,” said Rep. Tim Mahoney (DFL-St. Paul), the bill’s lead author and a member of Pipefitters Local 455.

Wage theft not just in the shadows

All this makes it sound like there are simply some “bad apples” hiding in the shadows in a few select industries. Yet a 2018 report by Good Jobs First and the Jobs with Justice Education Fund

found that, “Many of the largest companies in the United States have . . . been embroiled in hundreds of lawsuits over what is known as wage theft and have paid out billions of dollars to resolve the cases.” They conclude from their findings that very profitable big businesses, including Fortune 500 and Fortune Global 500 companies, remain heavily involved in wage theft.

“Among the dozen most penalized corporations, Walmart, with $1.4 billion in total settlements and fines is the only retailer,” states the report. “Second is FedEx with $502 million. Half of the top dozen are banks and insurance companies, including Bank of America ($381 million); Wells Fargo ($205 million); JPMorgan Chase ($160 million); and State Farm Insurance ($140 million). The top 25 also include prominent companies in sectors not typically associated with wage theft, including telecommunications (AT&T); information technology (Microsoft and Oracle); pharmaceuticals (Novartis); and investment services (Morgan Stanley and UBS).”

The rise of precarious work

Whether people work online, in a call center or at the back of the house in a restaurant, wage theft is a condition of employment for far too many. Fueling this trend are the new structural realities of the global capitalist system. In the so-called advanced economies including the U.S., the erosion of worker power, the decline of traditional private and public employment, outsourcing, automation and the worldwide collision of workers competing for jobs have all resulted in a rapid destruction of the very notion of steady, full-time work. And along with it, protections against hyper-exploitation that seemed common enough in the 20th Century are rapidly being replaced by the worst forms of domination and subjugation. In the Global South, wars and the brutal residue of colonialism and imperialism have guaranteed a dangerous and uncertain existence for vast sections of the population. Work everywhere is, or is becoming, precarious.

In the U.S., impacted the most are those already the most vulnerable to exploitation: people of color, immigrants, women, the disabled. But a growing sector of artists, musicians, cultural workers in general, information and communications workers, adjunct professors and others have become a systemic part of this informal, precarious economy. Wage theft isn’t the half of it, but it is a poignant and devastating tell of this deliberate and massive shift in power and work.

Back at the hearing, Kevin Osborn appealed to the committee to do something for the thousands of workers in Minnesota who are experiencing wage theft, workers who “need real enforcement against stolen wages, stronger protection against retaliation, and adequate funding for agencies to investigate and reclaim our lost tips and pay.”

A vote to pass HR6 out of the Labor Committee and on to its next committee will be taken on Wednesday, February 13.