C Olson – Grocery Workers 22×30, 4/28/20, 1:05 PM, 8C, 8142×10933 (262+340), 108%, Custom, 1/12 s, R77.9, G42.9, B57.4

Share

Two and a half years ago, an ensemble of willing and unwilling “heroes” embarked on a journey filled with suffering. They faced the impossible task of keeping society functioning through a disruptive, deadly disease outbreak. Many of these workers were forced to toil in unfavorable, uncertain conditions. Many fell ill. Many died. Those who survived were left with the losses of trauma and burnout. Some even got a few extra hundred dollars for their sacrifices.

These modern “heroes”—essential workers—are expected to risk their lives and the lives of those around them when they go to work every day. Without their labor, our ways of life would be even more disrupted than they already are by a deadly pandemic. This image of heroism for working through mass death and disabling events like pandemics and climate disasters only serves those who profit from underpaying and undervaluing the most essential work. The more essential your work is, the less you really earn. And we aren’t allowed to imagine a world without this exploitation because working is bred into us as a survival mechanism so that we contribute to reproducing a system that’s killing us.

A hero is someone who triumphs over obstacles, and instead of focusing on reducing obstacles, we try to build resilience against them. Instead of building resilience through care and reciprocity and collective power, we build resilience through cruelty, violence, and neglect. Since essential work is supposed to always be essential, and since most people on this planet need money to survive, there will always be people ready to sacrifice for low pay in an endless cycle of replacing and being replaced. Being an integral yet extremely expendable resource makes you a hero. In reality, the whole point of a hero is to die.

Take my father, for example. A U.S. Army veteran, he believed in serving his country, but he wouldn’t get vaccinated against COVID-19 to protect himself or those around him. After leaving the military, he pursued a career in information technology. I don’t think he really enjoyed his job because he’d come home angry about it and he would direct that anger onto me and our family. He prided himself on being the provider, and he acted entitled because of his hard work. When Best Buy outsourced his job and fired him in his fifties, he was unemployed for a while and he struggled. Less than two years after beginning work at Home Depot, he caught COVID-19 and died in December 2021. I believe he was a victim of political disinformation, as well as a victim of the economy’s brutal need for a vulnerable, disposable workforce.

Essential workers are still struggling to survive, let alone be the ones directly responsible for running the economy. A brief period of reverence for their labor quickly subsided as the narrative of a “labor shortage” began to dominate. Of course those at the top of the economic ladder had their interests prioritized, even as they raked in record profits while millions suffered and died. Now, millions will be forced out of work in order to curb inflation.

The labor movement is gaining momentum, and unions are seeing more attention in the media and government, but there is still an incredible imbalance leaning toward big business interests. A few Minnesota essential workers fought to receive one-time bonuses from the government, but their working conditions remain the same, and they’ve returned to that invisible place in our collective imagination as we pretend the status quo is back and roll back protections and mitigations. Instead of the structural and systemic changes that are so clearly needed to address the compounding crises in sectors such as healthcare, manufacturing, and agriculture, powerful forces have closed the door on what could’ve been an opportunity to transform how we perceive and value the humanity of labor.

We’ve all experienced loss and grief during this time, whether it was the loss of life, health, a job, a business, a home, a way of life, or a sense of belonging. The pandemic and its many crises should’ve been a gateway to a better world.

How do we get back to a place of shifting and widening worldviews? How do we protect each other now? How can we not just survive, but keep our spirits alive?

For exploring questions like these, I turn to art.

What is essential work and who counts as essential?

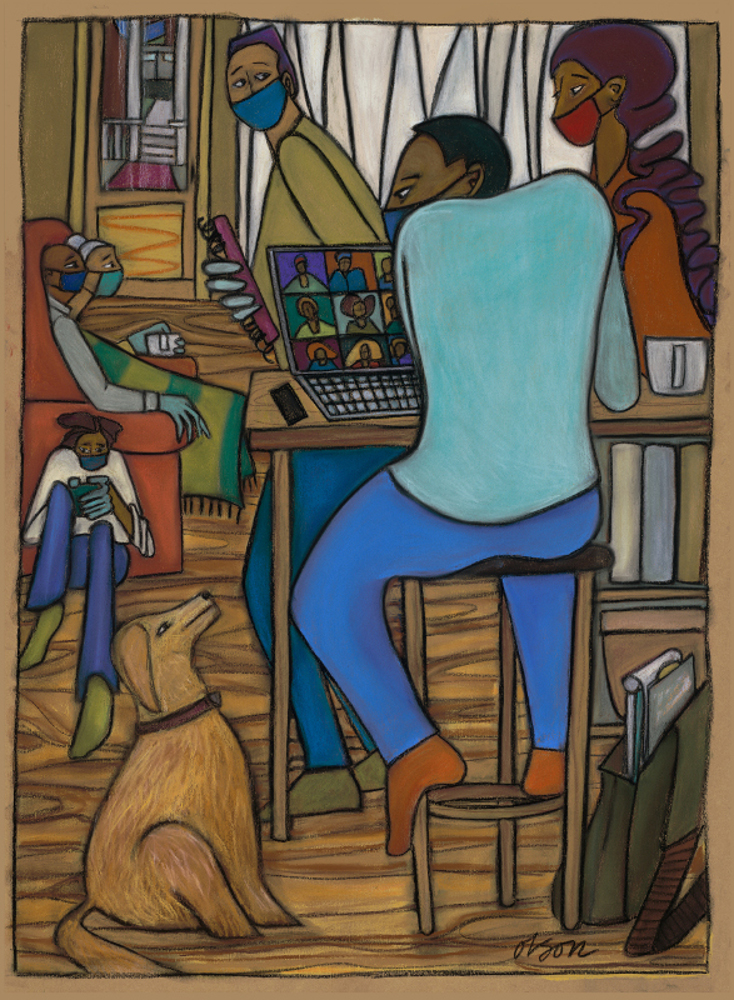

“As a narrative artist, I like to draw things that are in my life, and I often reflect on family and community,” Carolyn Olson, a narrative artist and former public school art teacher from Duluth, Minnesota, told me. From March 2020 to July 2021, she painted one hundred portraits of essential workers. Each portrait, a colorful pastel depicting workers in different roles, environments, and encounters, has an intentional story behind it. These work scenes were inspired by watching and listening to the effects of COVID-19 on communities and families. The art provided an outlet for Olson’s anxieties over the safety of essential workers, which included her own two children.

In July, Olson and I had a conversation over Zoom about her work. In September, I was able to attend an opening reception of the “Essential” show at Prove Collective gallery in Duluth that showed 100 prints of the original pastel drawings. I had seen the portraits up close in her self-published book. Peter Rachleff, co-executive director of East Side Freedom Library, a library focused on solidarity, justice, and advocacy based in St. Paul, even wrote an introduction for it. Getting to view the essential worker portraits in person and in community with Olson was a special moment.

The following July interview was edited for clarity.

WORKDAY MAGAZINE: Thank you for taking the time out of your schedule and talking with me. And thank you for making your art and the essential worker portraits book. I really enjoyed the introduction.

CAROLYN OLSON: We have 27-year-old twins living in the cities, living and working as essential workers. And it was the only thing I could think about. There were no vaccinations, and we weren’t hearing much. The panic for them both to go to work every day. One was in the grocery, one’s a teacher. It just turned everything upside down. I would post on Facebook, because I figured that there would be no gallery show. I actually met a lot of people that way, because we’re all stuck at home from all over the globe. We all shared our struggles. I also found that people found themselves in those images, and they found a relative. They found somebody that they didn’t think anyone’s paying attention to.

I volunteered at Second Harvest Heartland up here where we hand out food. And they said, nobody recognizes essential workers really. They say they do. But the person that stands outside the store and counts people, how unbelievably difficult. You’re face-to-face with somebody who had COVID, and you’re getting paid minimum wage. And people are anxious. These are all invisible people.

A lot of this we’d rather not discuss. Nothing is being done about wages anymore. Nothing is being done about housing, healthcare. I write the president every month and tell him, you need to forgive student loans. If you expect the 20 year olds to take care of this much. You gotta be kidding.

WM: Your paintings don’t only show the places and spheres where that interdependence exists, but they also show the encounters and human connections. I think our work is similar in that way. You’ve been making art about essential workers, and I’ve been reporting about them. When society fails to protect us and take care of our needs, this is how we protect each other, and how we protect ourselves, because when we protect others, we protect ourselves.

CO: I know people are tired of illness being around them. But I think the artwork and your articles bring up a different point of view. Nobody sees the people in the warehouse that have to work. One of the things I did with my images is show these are people that have to be face to face.

Nurses with the Minnesota Nurses Association held the largest private sector nursing strike for three days in September in the Twin Cities and Twin Ports to fight for patients over profits against the corporate greed of hospital executives.

I also wanted to talk to you about grief as well, because my dad actually passed away last December because of COVID. I’m going through this training about ambiguous loss and using that lens to ask questions and tell stories, because that’s how I find meaning in the meaningless. Community intervention is going to be really important, because we don’t have enough therapists to address all of this trauma and loss that we’re living through. Was it your intention to show the grief as well?

I often think, what do we do with it? It just keeps coming. And it comes in different ways. Like the passing of your father, I’m so sorry. Your family now will bear that, and you’re not alone, and that doesn’t make it any easier. It comes and goes and it comes in different spaces. And even if it wasn’t grief to death, there’s all these losses that people suffer for whatever reasons.

The grief was—is—a big part of it. I showed the images to a group in Chicago, and a woman said she was an election judge. And she had to look through the window at the nursing home to watch people because she couldn’t be next to them. In an effort to hold our democracy to some degree of continuing in a good way, we did things we never imagined we had to do. And we can’t ask people to risk that much.

Gravediggers and cemetery caretakers have a long history of labor activism.

WM: We take for granted what’s really important to our survival is just the connection to others and ourselves.

CO: I wanted to show that here’s this group of people from all walks of life doing their civic duty. How it should be. Kids doing kid things. Kids helping their parents with the groceries. One of the essential worker images, I had a kid voting with a hood on. I did it on purpose.

WM: I like the voters portrait because it hit me that essential workers are voters, and voters are essential. We shouldn’t have to demand a voice in how things are run.

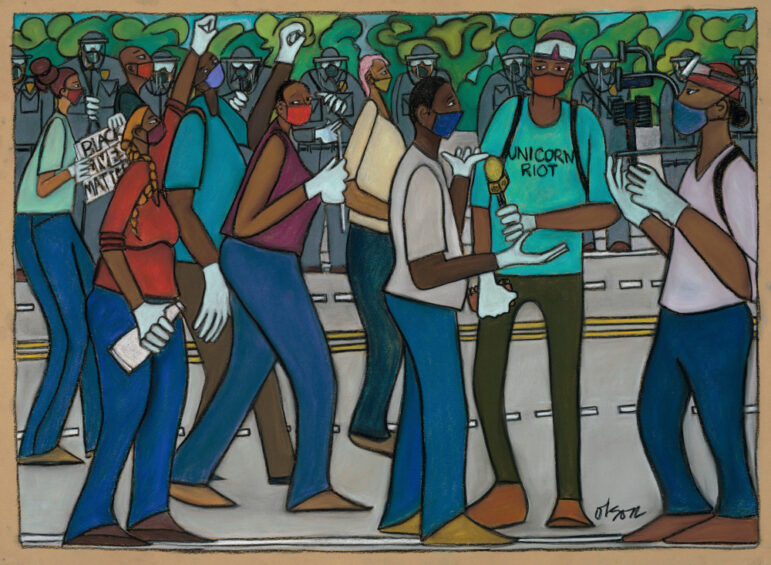

CO: During the protests, the marching, it was so important that people voiced their opinions. And I felt like it was a risk. You know, we would check in with our kids. Are you going? My daughter had to work every day. She had to ride her bike through the city. She’d say, “I can’t ride the bus. It’s like a Petri dish, Mom. I’ll get sick on the bus.”

WM: I wanted to ask about your children, too, because you said one is also a teacher, right?

CO: Yep, my son is a middle school band and orchestra teacher in the Minneapolis school district. This has been an intense year.

WM: Did he go on strike in March? What did you think of that, as a former teacher?

CO: I supported him 100%. What he was asking for was the bare minimum. They got some of it, as you know, but teachers didn’t get a heck of a lot. He’s working at a restaurant in the cities in the summers, and a little bit during the school year, and teaches lessons. And does that online. And then teaching full-time.

We have to keep the fire under how we treat public education. It’s a place of democracy, the only place your kids are going to be sitting next to someone who didn’t come from the same place.

Teachers and education support professionals with Minneapolis Public Schools went on strike for three weeks in March 2022. In 1970, Minneapolis public school teachers walked off the job in an illegal work stoppage which led to the passage of the Minnesota Public Employment Labor Relations Act (PELRA), a law that provides the right to bargain and strike.

WM: I think a lot about how we literally call it artwork. The ancient Egyptian artisans were actually some of the first people to go on strike in recorded history. Organized labor has always seen the usefulness of artists, and how they lead awareness. I’m wondering, what are your thoughts on art as work? And do you see artwork as essential?

CO: Society doesn’t always recognize what they do as work though. That’s the problem. Musicians do work. Dancers do work. Not just in the arts, but you know, cooks, chefs, seamstresses, welders. People still want good music, they want good clothes, they want something nice on their wall. This is your gift. My light bill will not recognize a gift like that. I have to pay the bill.

WM: I’ve experienced the pandemic through a Twin Cities lens. What was it like being in Duluth? How did you experience the pandemic?

CO: We buckled down and stayed in the house. I was feverishly working on those pastels, because that helped my anxiety. And then I could post them and I could say something.

The majority were very suspicious of everything. And it took a toll. But still, people didn’t want to believe it was happening. One of the pictures is of my old classroom. I heard about the janitor at school. The kids were there for summer basketball in 2020, and the janitor called the district office and he said they’re drinking from the drinking fountain. There’s no precautions. They’re not wearing masks. We have no plan, what is the plan? The water should have been shut off. Here he was, you know, in his late 50s, he couldn’t risk getting sick. He was in charge of this whole school, and no one was going to participate in following health rules. I drew a picture of him.

According to Eva Lopez, janitor and vice president of SEIU 26, thousands of her union members who cleaned buildings, offices, and retail stores during the pandemic missed work, and four died from COVID-19.

Before MPS teachers went on strike, MPS food service workers with SEIU 284 voted to go on strike, but they were able to reach a contract and avoided a work stoppage.

WM: I like that Nina Simone quote, “An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times.” And I think you’ve achieved that with this series. There are a few portraits of independent journalists. And I think that’s a very important distinction to me. I don’t work in a newsroom. There isn’t a big company overseeing what I’m writing. Why did you choose to represent that kind of journalist?

CO: I was getting real information out of those groups of people. It was a nod to Unicorn Riot. Because they were showing up at everything, and I needed to know what was going on. And I wasn’t getting it from WCCO. Also City Pages. They have always been trying to tell the story. And if you notice, I don’t usually use words in the images. Those two times I did because I needed people to realize there’s a difference. I’m not getting enough information from some of the traditional sources. Not a lot of people have asked me about that, to be honest with you.

Unicorn Riot is one of the news sources Olson went to for information during the pandemic and George Floyd uprising.

Olson told me she painted this right before City Pages closed down. Afterward, journalists from City Pages banded together to create the writer-owned online publication Racket.

WM: I’ve been analyzing a lot of media around the pandemic. There’s a lot of cognitive dissonance. When it comes to essential workers, one day we’re thanking them and then the next we’re abandoning them. One day we have this graph on pandemic deaths per occupation, but then the next day, it’s like, oh, let’s go back to normal. But normal is what got us here. These large media institutions are invested in going back to normal because they’re invested in the status quo, and they make money off of sensational, violent, traumatic stories. So it’s been difficult being close to this industry, seeing the narratives. Why do you call yourself a narrative artist versus just an artist?

CO: I don’t understand why we’re not all over why the news is not covering the fact that COVID isn’t over. Why are they not talking about what’s happening in the hospitals? It’s really in a bad place right now. And it’s like it’s invisible. We’re not talking about it at all.

There’s a whole conversation here and it’s gonna take time. It’s gonna take some building of trust. How much do you need? Are you afraid? And what are you afraid of? You’re afraid you’re gonna go hungry? Why can’t we be more open about how to manage our resources? It’s all based in fear.

We have to ask the questions. But I think first and foremost, we get the selfish folks out of positions of authority. We have to call out bosses. I have friends my age, they have businesses, and they said people just don’t work very hard. I’m sorry, I just don’t buy that! We’ve lost a million people. We don’t have workers anymore.

Narrative is because in my images, there’s a story involved in it, whether it’s a story of sisters getting their hair cut, kids playing a game, dinner together. Everything’s surrounded by story. We document the everyday things, how to live, how to live in a good way, and feel good about what you do. So I think for essential workers, the narrative part was to talk about these important folks. Keep the conversation going, in hopes that someone would say, how are we gonna make anything better?