Share

We’re looking back to 2011 when thousands of public workers and allies gathered around the Wisconsin State Capitol, universities, and satellite locations from February through June to protest the passage of Wisconsin Act 10.

These Occupy-era demonstrations not only included Wisconsin workers but also union members, labor organizers, and allies from across the United States – it is reported that 100,000 demonstrated at the peak of the protest.

Photos from the demonstrations show an incredible gathering in and around a wintery Madison capitol building. Wisconsin has a history of strong labor organizing and was the first state to legally recognize collective bargaining in 1959, and the passage of Wisconsin Act 10 has proved devastating for union membership numbers and access.

Embed from Getty ImagesHowever, the 2011 Wisconsin protests serve as a powerful reminder of the importance and public memory of mass demonstrations.

As WorkDay MN editor Filiberto Nolasco Gomez explained,

the organizing that happened was so iconic within the labor community. My Teaching Assistant local in California UAW 2865 sent one of our executive board members to represent Cali and our solidarity but also to bear witness. Madison was the site of the first teaching assistant union in the United States, honoring their presence and role in the Act 10 protest was important to 2865

“The Recent Evolution of Wisconsin Public Unionism Since Act 10,” just published in the Labor Studies Journal, documents the rippling effects of Wisconsin Act 10 on public worker unions and labor organizing since 2011.

Looking at case studies of Wisconsin’s AFSME, AFT-Wisconsin, SEIU, and WEAC public sector unions, authors David Knack,

This study helps us learn ways of reorganizing union structures and engaging in labor organizing as we face national and local level anti-union environments.

Wisconsin is the epicenter of a particularly restrictive anti-union policy called Act 10. Act 10 was passed in 2011 under Governor Scott Walker and a Republican-controlled state legislature included a 1 am forced vote which cut off debate and public hearings. Act 10 went through three years of litigation in the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

Act 10 requires public worker unions to (among other things):

- Undergo annual certification votes to maintain collective bargaining status

- Repeals the authority of

limited term employees, home healthaids ,child care workers, and UW faculty and academic staff from collective bargaining - Bargain only for base wages, and cap all potential raises to the Consumer Price Index

- Limit union contracts to one year (so members have to renew every year)

- Increase contributions to pension and copayments toward health insurance by at least 2 times

- Eliminate resolution mechanisms and worker representation for contractual disputes.

Act 10 is related to other “right to work” anti-union legislative tactics. All public workers are affected by Act 10 except for state patrol troopers and state patrol inspectors.

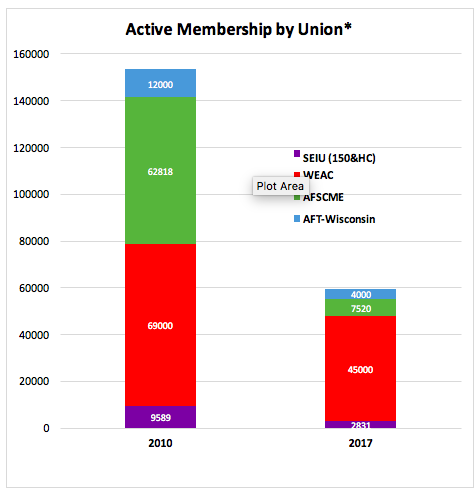

Overall, public-worker union chapters in Wisconsin have lost a lot of power and a considerable amount of union members – as the study documents, public sector union membership has declined by roughly 70% since the passage of Wisconsin Act 10. A more in-depth breakdown of union membership numbers over time follows:

Baxter,2018, Kohlaas 2018)

The study doesn’t romanticize Wisconsin’s public-worker union struggles. Some unions have collapsed into others, some unions had thousands of early retirees and then difficulty growing a new union membership base, some unions chose not to recertify every year and lost seats at the bargaining table, and some unions struggled to maintain traditional structures and procedures with no base membership to support leadership.

As one author David Nack explains,

“I think that even in Wisconsin, and certainly in other states, most people have no idea of the extent of the damage sustained by public worker unions as a result of Act 10. The ongoing loss of membership, along with most bargaining and union rights, is truly staggering. In essence it is a proven right wing strategy for how to eviscerate public worker unions in any “blue” state that the extreme right manages to take over, now or in the future. It’s a cautionary tale, and it also demonstrates the effectiveness of rank and file union democracy as a counter strategy to this kind of threat.”

Despite the drop in membership and revenue, unions are surviving and carving ways forward with reorganizing tactics and renewed interest in labor education. And there are larger-scope conversations to have around what we want union structure to look like, and how we want to engage in labor organizing going forward.

Public education unions like WEAC and MTI have shown a particular way of reorganizing post Act 10 that shows promise, growth, and the strength associated with adaptability.

Local chapters of WEAC and MTI have focused less on contract bargaining, employing professional staff, and union dues, and more on internal communication and regional committees. As the study reports:

“Amy M. Turkowski, a veteran first grade teacher and MTI faculty representative, and an elected member to MTI’s handbook bargaining committee provides insight into the work that she is engaged in: ‘I do a lot of work in small groups and usually MTI subcommittees with District personnel, working out the nuances of the handbook … I’ve worked on the school calendar, on that subcommittee, it’s a small group of four of us with district representatives. We kind of fine tune the details of the school calendar.’ As the faculty representative in her school Amy is also an internal organizer, approaching new faculty about joining MTI, and using problem solving techniques as much as possible in representing her members. Reflecting on the changes that she’s seen since Act 10, she muses: ‘Before Act 10 it was a kind of top down dissemination of information. Now it feels more grass roots. There’s more subcommittees, there’s more action committees… There’s a little more ‘we’ … I feel more empowered now than I did before.’”

And although public education employees have a uniquely public-facing position in the community compared to other public workers, successful changes in WEAC and MTI can serve as a rough model for other unions as they navigate anti-union environments.

These models and expansive ideas on how unions can operate are important as we navigate anti-union environments created by policies like Act 10 and, more recently, the 2018 Supreme Court Janus Decision.