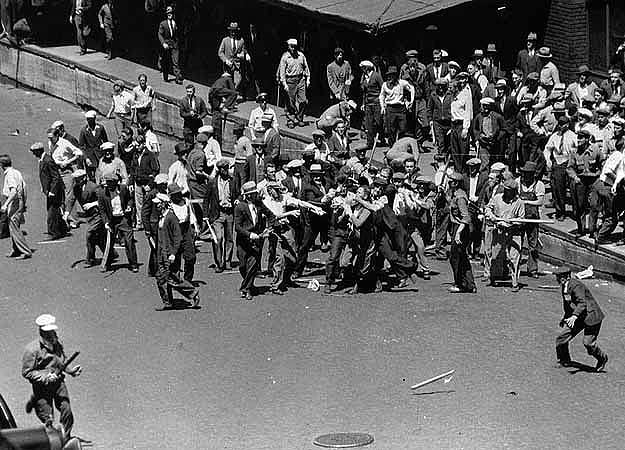

People’s Lobby members occupy the Minnesota state senate chambers on April 5, 1937. Image from the Minnesota Historical Society.

Share

Workers and unions across the U.S. are raising the alarm about the Trump administration’s attempts to divide the working class.

“They want us to be distracted by attacking the working class on innumerable fronts, but we must stand united,” said University of Minnesota Twin Cities graduate worker Greyson Arnold at a recent rally organized by AFSCME 3800, which represents clerical workers, and GLU-UE Local 1105, which represents graduate workers.

The Amazon Labor Union-IBT Local 1 located in Staten Island, New York, released a statement on immigrant solidarity, saying they refuse to be divided: “By standing together across all lines of difference, we are building a movement stronger than their fear tactics, stronger than their threats. That unity will break their divide-and-conquer strategy and make real change possible. We call on workers, communities, and the labor movement to join us in defending immigrant rights as a core labor issue. A threat to one is a threat to all, and we will not stand by while our coworkers are targeted.”

Union leaders have pointed to the importance of building worker power in response to division attempts. “When they come after one group, they come for us all,” said Association of Flight Attendants International President Sara Nelson at a rally for Delta Air Lines workers in January. “Nothing on this Earth turns without us. If we understand our power in this moment and we organize together and have each other’s backs, we can take action. Strike action, organized action, moral action.”

In an interview with Bob Hennelly, Nelson said that after the elimination of collective bargaining rights for Transportation Security Administration workers by the Department of Homeland Security, workers have “very few options but to join together to organize a general strike.”

On March 27, President Trump signed an executive order to end collective bargaining for many federal employees, which Minnesota AFL-CIO president Bernie Burnham has called “unprecedented union busting.”

The Minnesota AFL-CIO also released a statement on January 26 in support of immigrant workers. “Trump and his billionaire friends are counting on workers to turn on one another while they cut their own taxes, gut worker safety standards, roll back union rights, and more,” the statement reads. “Every worker should remember that an immigrant doesn’t stand between you and a better life – a billionaire does.”

Workers have a long and storied history of resisting attempts to pit them against each other. We found examples specific to Minnesota’s labor movement, which has a militant legacy that can be learned from today. Workers organized and mobilized to take defensive and offensive measures against various forces—hate groups, corporations, and corporate-backed elected officials—that sought to violently divide their communities and hoard resources.

Teamsters Local 574 Forms Union Defense Guard in 1938

In “It can’t happen here?” Joe Allen wrote about the Teamsters’ fight against the Silver Shirts in Minneapolis. The global economic crises of the 1920s and ‘30s empowered a rise in fascism. Hate groups formed in Europe and the United States, and Minneapolis was host to one of the largest chapters of the nationalist, fascist, and pro-Nazi Silver Shirts, AKA the Silver Legion of America. Sarah Atwood wrote about the organization for Minnesota History. Founded on January 30, 1933, as a paramilitary organization by journalist and Christian mystic William Dudley Pelley, the group also faced opposition in Minnesota, where the informal Anti-Defamation Council was organized to investigate antisemitism. In 1936, journalist Eric Sevareid began reporting on the Silver Shirts for the Minneapolis Journal, hoping to raise the alarm, although he felt his editors were framing the organization as unserious.

In Teamster Politics, union activist, communist organizer, and historian Farrell Dobbs wrote about the Union Defense Guard, which was a group of union members that mobilized to confront the Silver Shirts in 1938, four years after Teamsters Local 574 (also known as Local 544 in some sources) led the truckers’ strike that transformed Minneapolis into a union town. Dobbs was one of the initiators of the strike, which challenged the Citizen’s Alliance, an anti-union business oligarchy that was renamed to Associated Industries. When the Silver Shirts came to town, they threatened to raid the union’s headquarters and were using violent rhetoric against the re-election of Farmer-Labor governor Elmer Benson. Local 574 staff, Indigenous worker, and military veteran Ray Rainbolt was commander of the Union Defense Guard, a multi-union formation that set up combat defense training and an intelligence unit for hundreds of union members. When Silver Shirts leader Pelley came to Minneapolis to deliver a speech, his cab driver reported it to Rainbolt, who led the Union Defense Guard to where Pelley was scheduled to speak. The audience that had gathered left, and Pelley fled the city. The Union Defense Guard thwarted other Silver Shirt gatherings in Minneapolis, and after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Pelley disbanded the organization.

Immigrant Women-Led Resistance in the Iron Range Strike of 1916

On June 2, 1916, after receiving a smaller paycheck than expected, Joe Greeni walked off the job at St. James Mine near Aurora, Minn., spontaneously sparking what would become a violent and deadly strike against the largest corporation in the United States at the time, a U.S. Steel subsidiary called Oliver Mining Company. Many different ethnic groups of immigrants worked in the mines, and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) sponsored parades and dances to bring people together during the strike. Women, who were included as members of the union, regularly attended these events and played active roles in strike defense, refusing to be intimidated and sometimes going to jail for peaceful and violent resistance in support of the strike.

On July 28, private armed deputies hired by the company tried to shut down a parade, and women defended the marchers by rushing to the front. On another occasion reported in August by the pro-labor Mesaba Ore, women physically resisted against mine guards denying them access to fresh water at mining camps, where the company sometimes cut off access to wells. In late July, mine worker Louis Stremola was arrested for interfering with the arrest of a woman, allowing her to escape custody. Although the miners lost the strike, workers and their families were militant in their resistance to the oppression of the companies that wielded control over their communities.

In an analysis on the strike for the Mining History Journal, historical researcher and writer Pamela R. Stek wrote that the media, controlled by companies, focused on the transgression of gender norms to question immigrants’ citizenship and roles as mothers in order to paint them as dangerous agitators: “Women strike activists faced public censure when anti-strike reporters and editors denounced female strike supporters as unfit mothers and suggested that an IWW victory would lead to the breakdown of family and society.”

The People’s Pilgrimage of 1937

According to MNopedia, the Workers Alliance, an organization that mobilized unemployed workers across the U.S., established a temporary branch in Minnesota called the People’s Lobby. On April 4, 1937, they gathered over a thousand people at the state capitol in support of governor Benson’s legislative package allocating $17 million in aid to the unemployed. What began as a demonstration turned into an overnight occupation after an activist used a knife to open the senate chamber door. Around 200 people peacefully occupied the chambers overnight, where they gave speeches, sang songs, and ate hot dogs. Benson addressed the demonstration, speaking against the senate and corporate interests that were opposing higher taxes for the wealthy. He vocalized his support for the protesters, who left in the morning at Benson’s request.

Benson was used to raising the ire of Republicans; during his time as governor, the Republican-controlled Senate blocked many of Benson’s radical proposals. Following the sit-in, Republican senators accused Benson of encouraging intimidation. The protest made national news, but Benson’s package did not pass, and Minnesota’s economy experienced a recession later that year.