Share

The world lost a musical icon on April 21. You’ll read about his impact as a musician and an entertainer elsewhere, but let’s take a second to look at Prince’s career-spanning fights on behalf of working people.

For more than 40 years, Prince was a union member, a long-standing member of both the Twin Cities Musicians Local 30-73 of the American Federation of Musicians and SAG-AFTRA, the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists.

Beginning with “Ronnie Talk to Russia” in 1981 on through hits like “Sign o’ the Times” and later works like “We March” and “Baltimore,” Prince’s music often reflected the dreams, struggles, fears and hopes of working people. And he wasn’t limited to words; his Baltimore concert in the wake of Freddie Gray’s death raised funds to help the city recover.

Few of America’s artists have so well captured the plight of working Americans as Prince, putting him in the line of artists like Woody Guthrie and Bruce Springsteen as working-class heroes.

Ray Hair, president of AFM, spoke of Prince’s importance: “We are devastated about the loss of Prince, a member of our union for over 40 years. Prince was not only a talented and innovative musician, but also a true champion of musicians’ rights. Musicians—and fans throughout the world—will miss him. Our thoughts are with his family, friends and fans grieving right now.”

And this is a key part of his legacy. Prince was deeply talented and could have easily made his success without much help from others. And yet he was a massive supporter of other artists, from writing and producing songs for artists as diverse as Chaka Khan, the Bangles, Sinéad O’Connor, Vanity, Morris Day and the Time and Tevin Campbell (among many others) to his mentoring and elevating of women in music, to the time where he put his own career on the line in defense of the rights of artists. And every musician that came after owes him a debt of gratitude.

The music industry has a deeply troubled past, with stories of corporations exploiting musicians, especially African-American musicians, being plentiful enough to fill libraries. At the height of his popularity, Prince decided that he would fight back. He was set, financially and career-wise, and had nothing to gain from taking on the onerous contracts that artists were saddled with when they were young, inexperienced and hungry. If he lost everything by taking on the industry, he still had money and fame to rely on. But he knew this wasn’t true for many other musicians, and Prince was always a fan of music, and he knew that taking on this battle would help others. So he took on the recording industry on behalf of music. On behalf of the industry’s working people—the musicians themselves.

And it cost him his name and his fame.

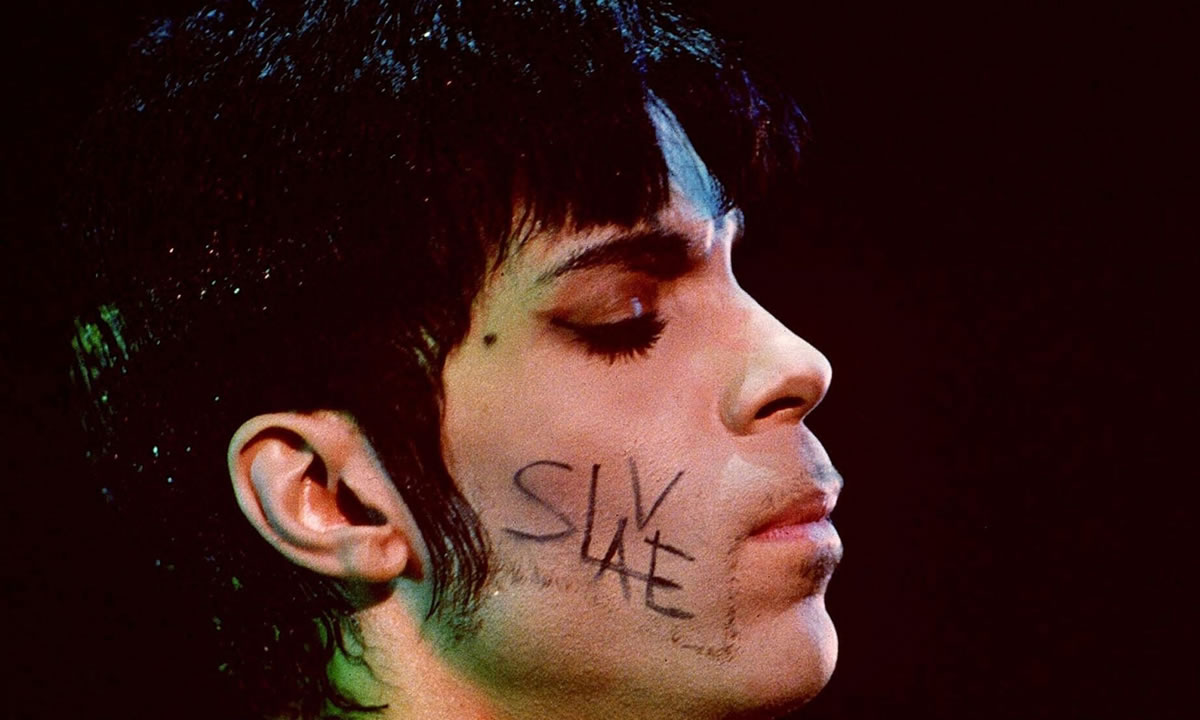

In the ensuing battle, Prince famously renounced his birth name and began performing under an unpronounceable symbol instead of a name. He fought the company at every turn, even writing the word “slave” on his face in protest of the conditions he worked under.

He said: “People think I’m a crazy fool for writing ‘slave’ on my face. But if I can’t do what I want to do, what am I?” For the rest of his career, which never recovered to his early heights, he continually fought to change the way that record companies treated artists, explored new ways to distribute music to fans and battled to give artists more control and more revenue for the art they create.

In a still-changing musical landscape, Prince was one of a handful of artists who helped shape a future where musicians, working people, get the fruits of their labor.

This article is reprinted from AFL-CIO Now, the blog of the national labor federation.