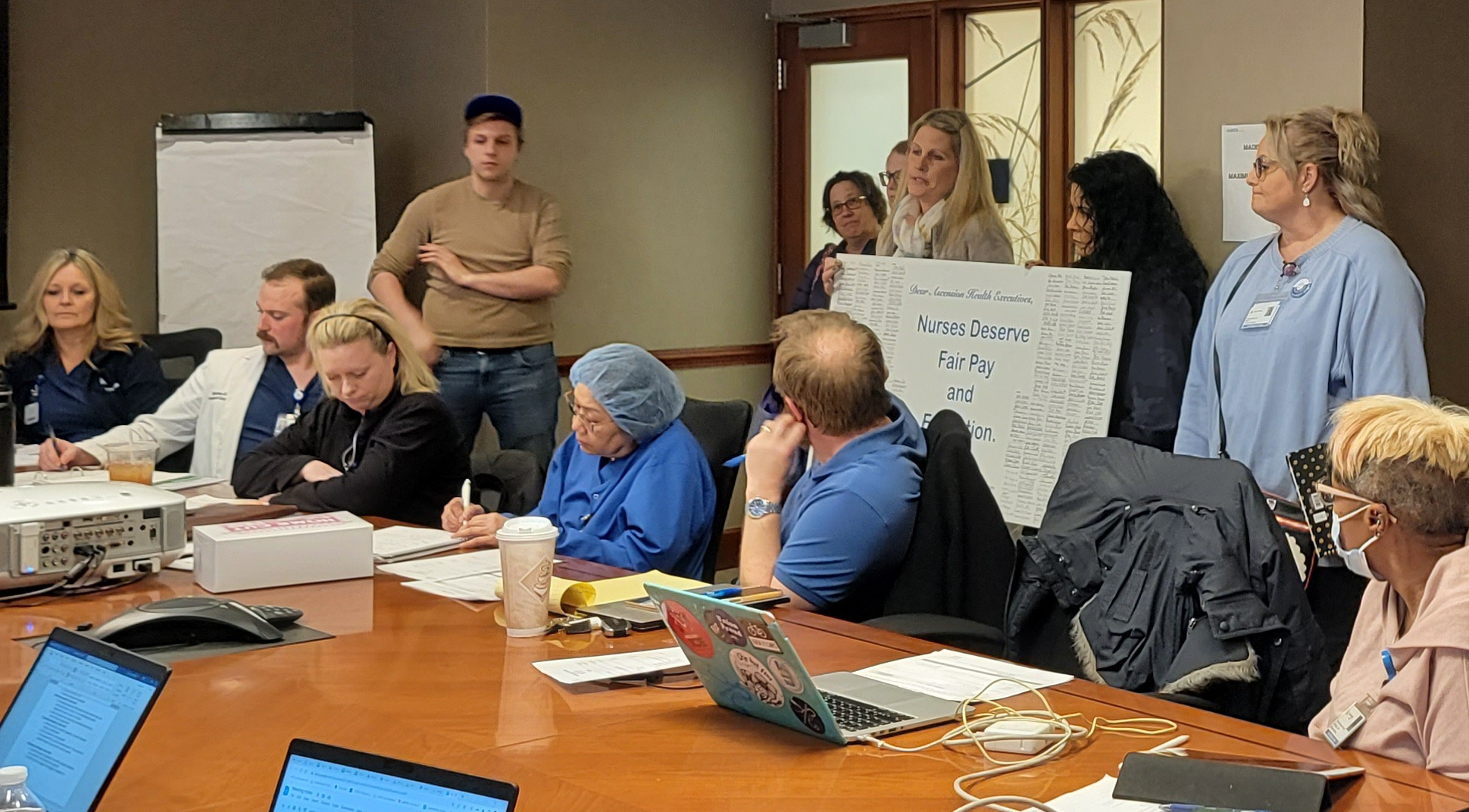

Nurses present a petition to Ascension management signed by hundreds of their coworkers calling for fair pay. (Photo courtesy of INA)

Share

Tania is a mother of four and a new registered nurse in the intensive care unit at Ascension St. Joseph Medical Center in Joliet, Illinois, also known as St. Joe’s. On May 30, at a bargaining meeting with management to negotiate for the union’s next contract, she gave testimony about how her employer allegedly treated her for bringing up safety issues.

“I was two weeks off orientation and I was given four acute care patients. I texted our manager… and said ‘this is a recipe for disaster. I can’t handle this,’” she said in her testimony, which was emailed to Workday Magazine by her union, Illinois Nurses Association (INA). Concerned about safety for herself and her patients, Tania said she declined to clock in during the incident last fall.

What came next was retaliation, says Tania, who is going by a pseudonym to protect her from further repercussions. “I was penalized because I said four patients was too much.”

Nurses at St. Joe’s negotiating for their next contract have been alerting the hospital and state government—through personal pleas and formal complaints—to the extreme levels of understaffing they say they’re experiencing. But there has been a disturbing lack of response to their complaints, they say, alongside retaliation for speaking out.

This is despite the fact that, in 2021, Illinois passed a safe staffing law, the Nurse Staffing Improvement Act, which requires hospitals to have written safety plans, and gives the Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH) the ability to impose fines for failure to comply. The law also provides a channel for hospital employees to file complaints about violations internally, as well as to the IDPH. Under the Act, the IDPH has discretion to conduct investigations, impose fines, and impose improvement plans on hospitals. The Act also includes some measures to protect workers from retaliation for doing so.

But INA says that St. Joe’s is failing to comply with the law. The union also alleges that IDPH is failing to adequately use its discretion to regulate according to the rule, placing both nurses and patients in harm’s way.

Alongside harrowing conditions, nurses describe their struggles with organizing in feminized labor as mothers. In her testimony, Tania said she has received offers to work at other hospitals, but wants to stay at St. Joe’s to grow her skills. “My friends say I’m an idiot. Maybe I am one,” she said in her statement. “All of my friends make more than I do.”

“I stay,” she added, “because my kids need me and I need stability.”

Widespread complaints

Workday Magazine reviewed 69 Assignment Despite Objection (ADO) forms from the month of May alone. A spokesperson for INA explains that ADOs are “union forms that are filed with the hospital, and a copy is filed with the Union.”

In May of 2023, nurses filed at least one ADO almost every day, and some days had multiple complaints—May 23, for example, saw six complaints total. John Fitzgerald, the INA representative for St. Joe’s, says usually around 100 complaints are made each month, but nurses have gotten out of practice filing them because of a lack of response.

The complaints from May tell the story of nurses who are overstretched, exhausted, and concerned about the safety of their patients.

One ADO from May 9 describes nurses being assigned five patients each, a particular concern given that the patients were allegedly high acuity. Another from May 16 states, “Nurses all have six patients. High acuity… Cardiac drips, multiple procedures. Unsafe staffing.”

Another from May 20 states, “Very unsafe! Very busy.” The nurse adds, “No breaks taken.”

These concerns are not new. One ADO form, dated May 23, 2022, was authored by nurse Beth Corsetti and signed by her and three other nurses. It states, “Nonstop admissions and discharges! No breaks, no lunch! We are human beings!”

Corsetti circled the names of the hospital leaders at St. Joe’s addressed at the top. Next to the circled names, she wrote, “Do something! We are drowning!”

“Hire more nursing staff and aids. Increase pay rate of all nurses to retain them,” she urged.

This ADO was accompanied by a formal complaint to the IDPH; the agency has confirmed receipt but has not made a ruling, INA says.

Allegations of noncompliance

These forms, along with testimony from nurses, allege a pattern of noncompliance with the Nurse Staffing Improvement Act. Instead of enforcing the law, and paying nurses better wages, nurses say Ascension’s behavior is hurting the community it’s supposed to help. (In 2018, Ascension, one of the largest private healthcare networks in the United States, acquired St. Joe’s.)

Fitzgerald explains that the Nurse Staffing Improvement Act from 2021 amends the Hospital Licensing Act to require staffing guidelines developed by committees for inpatient units and emergency departments. Instead of fixed ratios, guidelines establish minimum levels of staffing in the form of grids.

“Let’s say that the staffing grid calls for eight nurses, if you have 25 patients, for instance,” he explains to Workday Magazine. “The issue is that if you look at these ADOs, you can see over and over and over again, they’re not staffing to the base grid. The acuity would call for another nurse, but we’re already short.”

Nurses and their advocates say St. Joe’s is flagrantly violating the law, and that the IDPH is failing to fulfill its duty to enforce the rules, designed to protect both nurses and patients.

“The law says that there are minimum staffing guidelines, and that they need to increase staffing with acuity, and they don’t meet those bare minimums,” says Fitzgerald.

According to Will Bloom, a Chicago-based labor lawyer who has represented INA, “Ascension’s repeated short staffing of particular departments could well constitute a pattern of practice of failing to substantially comply with requirements of the statutes and the hospitals’ written staffing plan.”

An IDPH spokesperson told Workday Magazine that it “issued a Notice of Violation to Ascension St. Joseph-Joliet in March for failing to meet nurse staffing levels by patient acuity under the Hospital Licensing Act and state regulations. The Nurse Staffing Improvement Act that you mentioned was an amendment of the Hospital Licensing Act and we are well aware of it.”

“Due to the fact that this is an ongoing and open investigation,” the spokesperson said, “we are not in a position to discuss the details and specific status of the case.”

Illinois state senator Rachel Ventura told Workday Magazine over the phone, “Now that they are in a 60-day cycle of being held accountable for that staffing plan, I think that what it shows is a history of this hospital not putting their patients first, because if you don’t have enough staff, doctors, nurses who are qualified for the care, then you put your patients at risk. And I think that it is criminal that this hospital continues to operate under those types of conditions.”

According to a statement from an Ascension spokesperson, emailed to Workday Magazine, “St. Joseph takes any and all complaints from our associates seriously, and addresses those issues appropriately and as agreed to under the collective bargaining agreement.”

The current contract between the nurses and the hospital expires July 19. Nurses are calling for better wages and safer staffing, including mechanisms for enforcement, like hazard pay for nurses who face understaffing.

Concern about lack of response

Fitzgerald says IDPH is tasked with regulation according to the Nurse Staffing Improvement Act, but the body is “asleep at the switch.”

According to the Hospital Licensing Act, any hospital employee may file a complaint with IDPH about an alleged violation. If the hospital is found to have a pattern of failing to comply with the law, the hospital must provide a plan of correction to IDPH, which has discretion to fine hospitals for violations.

Fitzgerald says the nurses have filed dozens of complaints with the IDPH. (ADOs are often used as evidence in IDPH complaints.) But, he says, the department has not taken aggressive action to address these nurses’ concerns.

Sen. Ventura, referring to oversight of staffing improvement plans at St. Joe’s, said, “I have encouraged IDPH to stay on top of this. I’ve asked them to aggressively look at that plan and really make sure that it aligns with the needs of health care and public health. And I have also contacted the governor’s office to notify them of how important it is for IDPH to be the oversight of public health and our hospitals in it.”

In response to the urgings of Ventura, the IDPH spokesperson said, “we are aware of the concerns expressed by members of the community and are responding appropriately under the authority provided by state law.”

The department said, “we can assure you that IDPH is strongly committed to carrying out its duties to protect patient safety and quality of care under both state and federal law.”

But INA has raised concerns about past incidents where the IDPH did not find merit in nurses’ complaints, or claimed that it did not have jurisdiction.

Workday Magazine reviewed a formal complaint to IDPH filed by Tania, based on her experience last fall. In that complaint, she goes into more detail about the alleged retaliation she faced, explaining that “the hospital decided to reprimand us for speaking up about the unsafe staffing. By giving me and the four other nurses a final warning reprimand. This entails we are not entitled to an incentive if we pick up extra shift, we cannot transfer to another department, we cannot be promoted and so much more. This reprimand is to last for one year. I am writing to bring your awareness to this injustice and retaliation.”

On November 15, the IDPH responded to her complaint in a letter, viewed by Workday Magazine. It states, “we do not find that the nature of your concerns establishes the potential for a significant health or safety deficiency under federal requirements. Consequently, we cannot request an authorization from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) for an investigation.”

According to INA, one complaint made by another nurse on November 3 detailing the same events Tania testified about was found to have merit by IDPH. But the union says it is still waiting for corrective action.

The IDPH has previously said that it does not have jurisdiction over labor issues, and has used this justification to dismiss complaints. Workday Magazine viewed the IDPH’s response to a November 21, 2022 complaint from a St. Joe’s nurse, provided by INA. The IDPH stated, “IDPH does not have jurisdiction over staffing or labor issues such as those you mentioned in your e-mail.”

But Bloom says, “Under Illinois law, the IDPH clearly has the ability to investigate violations of the statute, as well as to demand corrections and impose fines. Under a pretty fair reading, the statutory language clearly empowers them to do this. Jurisdiction can be a term of art in a lot of spaces, but I think it’s hard to avoid the clear language from the statute.”

According to INA, in the context of a hospital, staffing and labor issues are public safety issues. The union is concerned about IDPH’s reticence to intercede, and is also worried about the opacity surrounding enforcement. “This is not a ‘labor dispute’ issue so much as it is a public safety issue,” the union said in a statement emailed to Workday Magazine.

There is evidence that staffing levels have a tremendous impact on patient safety across the board. A 2021 University of Pennsylvania study looking at nurse staffing ratios in Illinois found that thousands of deaths could be avoided, the length of patient stays could decrease, and hospitals could save money, if nurses were only assigned to no more than four patients at a time.

For this reason, the union says that the IDPH does have jurisdiction under the Hospital Licensing Act, and should be using its discretion to enforce safety.

Holding the boss accountable

Ascension has been under growing scrutiny. A December 2022 New York Times investigation analyzing staffing cuts at St. Joe’s and Ascension Genesys in Michigan found that the company allegedly made an effort to reduce labor costs in order to line the pockets of executives in the years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic. Reports by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and Milwaukee Magazine highlighting the closure of a labor and delivery unit and a lack of safety due to staffing shortages in Wisconsin inspired Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) to write a letter to Ascension CEO Joseph Impicciche in February demanding transparency around its Wall Street-like investment practices, revealed by STAT. In addition to understaffing, several nurses at St. Joe’s are suing Ascension over alleged wage theft.

“In this workplace, we have a situation where the boss either ignores issues being brought to their attention, or goes through a grievance process, goes through arbitration, as it resolves, signs settlements, and still doesn’t pay these workers out,” said Bloom. “Everything else they’ve tried to get their employer to do the baseline work of paying them accurately, has not gotten Ascension to do the right thing.”

Due to alleged unsafe staffing, nurses in negotiations for contracts at Ascension hospitals in Texas and Kansas performed one-day strikes on June 27. According to National Nurses United, the nurses were locked out following their one-day strike.

In response to INA’s concerns at St. Joe’s, the spokesperson from Ascension told Workday Magazine over email, “As a ministry of the Catholic Church, we affirm the right of our associates to organize. The management team at Ascension St. Joseph has, and continues, to negotiate in good faith with the union and their representatives. We have participated in active and timely negotiations with the union, including the exchange of good faith offers and the appropriate and timely consideration of counter offers.”

“Ascension St. Joseph takes any and all complaints from our associates seriously, and addresses those issues appropriately and as agreed to under the collective bargaining agreement,” the spokesperson continued.

“Staffing challenges are impacting hospitals across the country, and Illinois is no exception,” said the Ascension spokesperson. “We are actively recruiting for nurses to strengthen the staffing at Ascension St. Joseph. This would typically include using other Ascension nurses to provide temporary staffing solutions in times of need. However, the current collective bargaining agreement prohibits us from bringing in all available temporary staffing support.”

In response to Ascension’s remarks, INA said, “We are happy to hear the employer claim publicly that they are unable to use temporary Ascension agency staff because of our collective bargaining agreement. However, this runs counter to the reality we have seen during recent months in which we have been forced to file a charge with the NLRB over the company’s staffing of St. Joseph’s with Ascension agency nurses.”

“We maintain,” INA added, “that the key to facing the ‘staffing challenges’ they cite is to redirect money away from executive bonuses and toward paying a fair and competitive wage to nurses who have lived in and served the Joliet community for years.”

Ascension would not comment on active litigation, but said “we are vigorously defending the matter you reference and deny any wrongdoing.”

On the front lines of healthcare and motherhood

Despite the challenges, new mothers and new nurses at St. Joe’s have been getting more involved with the union since the last time they went on strike in the summer of 2020.

“My first week at St. Joe’s was when the country got shut down. Pandemic nursing is all I’ve ever known,” said Kaitlynd French, a new mother to two children and the sole income provider for her family as a new registered nurse in the medical oncology unit.

French started going to union meetings after going on strike as a brand new nurse in the summer of 2020. “I want our hospital to be safely staffed. I want us to be paid appropriately. But it’s almost like every step I take towards trying to help, I feel like I’m taking a step away from my family,” said French. “If I take any sort of time off from work, in the back of my mind is how am I going to be able to support my family?”

Looking to give her husband a break from caregiving, she asked the childcare center that had been providing her son with at-home speech therapy during the pandemic if they could take in her daughter for a few days per week, but they told her they didn’t have enough staff.

Kristin Barnett took up a position as a registered nurse in the medical surgery unit at St. Joe’s so she could have more days at home with her three children, the youngest she gave birth to during the pandemic.

“It’s hard because the days that I do work, I don’t see my children at all, because it’s so early, by the time I get home, they’re in bed,” she said. “It’s nice to be at work, but there’s so much guilt about not being home. When I’m home, then I have guilt about them being short at work.”

She said she spends a lot of time looking at schedules, a type of mental labor often performed by mothers. She hears coworkers say they want to be more active in their union, but there just isn’t enough time. “If I’ve been at work for two, three days, and then there’s a union meeting, I might have to miss that, because I haven’t seen my kids in a couple days,” said Barnett. “I just have to feel okay with saying no in both areas of my life. My kids understand too. It’s important for me to have them see that I worked hard for my degree and I want to work and that I’d love to be home with them.”

On top of balancing work and family, union organizing cuts into their schedules. French and Barnett are both active members of their union. They say phone calls and Zoom meetings have been helpful, but another way their union has helped is by providing childcare during bargaining meetings with their employer.

“I could not have dealt with this crap having little kids,” said Robyn Richards, who has worked in the ambulatory surgery unit for the past five years. Before that, she was in the orthopedic unit, where she worked for 16 years. Not only does she have a mother who worked as a nurse, both her sister and sister-in-law are nurses, and her daughter is also a nurse working the same orthopedic unit that Richards left because of declining working conditions.

“If [Ascension] would just freakin’ loosen the purse strings and pay attention to how this is really affecting our community,” she said, “then maybe things could get better.”