Share

It’s hard to imagine a beautiful flower has anything to do with the ugly side of free trade and globalization. But for Josefa Gomez and other workers in the profitable flower industry of Colombia, providing bouquets for U.S. and world vases has meant increasing hours with falling pay, growing health problems and human rights violations.

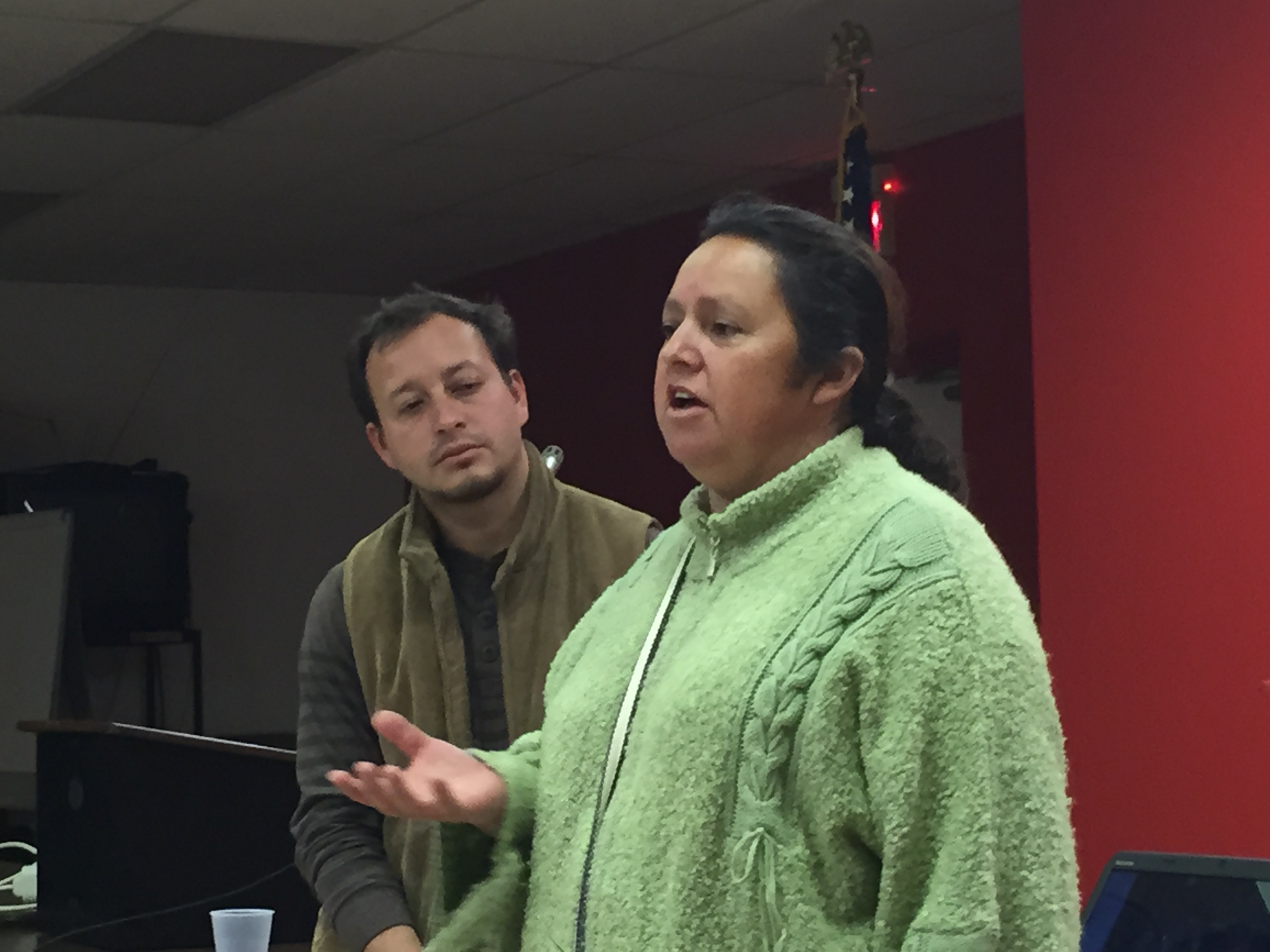

Gomez was a flower worker for 15 years and is now an organizer with the Colombian workers’ organization, Cactus. She and fellow Cactus organizer Leonardo Luna Alzate spoke at a Minneapolis event on Tuesday sponsored by Witness for Peace and the Minnesota Fair Trade Coalition.

“You do repetitive work with no breaks, typically hunched over and in other positions that are very uncomfortable so you get injured,” she said through an interpreter. “And the pesticides used effect our health. Workers get skin illnesses, blood illnesses, even cancer. Women have had miscarriages as a result of the chemicals.”

Sixty-nine percent of Colombia’s 130,000 flower workers are women. The majority are heads of households or single mothers. Most are hired on short-term contracts of three to six months, which are not renewed for workers who become pregnant or ill. The work has helped many escape poverty in the countryside but the competitive pressures of free trade continually make their situation worse.

“The company I worked for started pressuring us to extend our shifts and work longer – for free – supposedly in order to save the company from bankruptcy,” said Gomez. “They had changed the name of the company and were saying it was different but it was still the same owners.”

Companies in Colombia often use the strategy of changing their name and liquidating contracts in order to bring in new workers at lower wages.

“It’s a way to get rid of workers with occupational illnesses or more senior workers who have been with the company 18, 20, 25 years and who would otherwise be getting close to retiring and getting a pension,” Gomez added.

Gomez and other workers organized a union as a result but forming a union is a dangerous thing in Colombia and companies have a lot of leverage to violate worker’s rights. “All the organized workers were locked out,” she said, “and there were guards there with dogs that were meant to keep us out and off of company property.”

“I really think that the flower industry is the clearest example of how the free trade agreements don’t help the workers,” said Leonardo Luna Alzate. “The Labor Action Plan hasn’t resulted in any improvement in the quality or quantity of jobs. If anything, the opposite.”

The United States signed a bilateral trade agreement with Colombia in 2012. During negotiations, labor and rights groups forced attention on Colombia’s abysmal human rights record, particularly worker’s rights. A blueprint for improvement called the Colombian Action Plan Related to Labor Rights, otherwise known as the Labor Action Plan, became part of the process. It was supposed to use the economic carrot of increased trade and economic development to force change.

“The flower sector is one of five sectors highlighted in that Labor Action Plan to look for improvements in workers rights and human rights and specific changes in the work environment,” said Elise Roberts, Upper Midwest Coordinator of Witness for Peace. Little has changed.

Colombia is an increasingly important beachhead for U.S. interests on a continent where there are serious challenges to U.S. models of globalization. It’s the second-largest recipient of U.S. military dollars after Israel and charges continue that this massive military aide is being diverted from policing the drug trade to violently suppressing union and other organizing.

Flowers are an important part of the trade relationship between the United States and Colombia and a very important part of Colombia’s economy.

“There’s a really clear supply-demand relationship between the U.S. and Colombia,” suggested Alzate. “Almost all flowers that leave Colombia come to the U.S. and almost all U.S. flowers come from Colombia.”

Seventy-six percent of Colombian flowers are sold in the U.S. They’re the country’s fifth largest export product, netting $1.2 to $1.3 billion per year in profits. Yet as profitable as the industry is in Colombia, the real dollars are in the United States.

“The largest profits that are made in the flower industry are not in the production at the local level in Colombia,” said Alzate, “they’re in the distribution and the marketing of those flowers in the United States.”