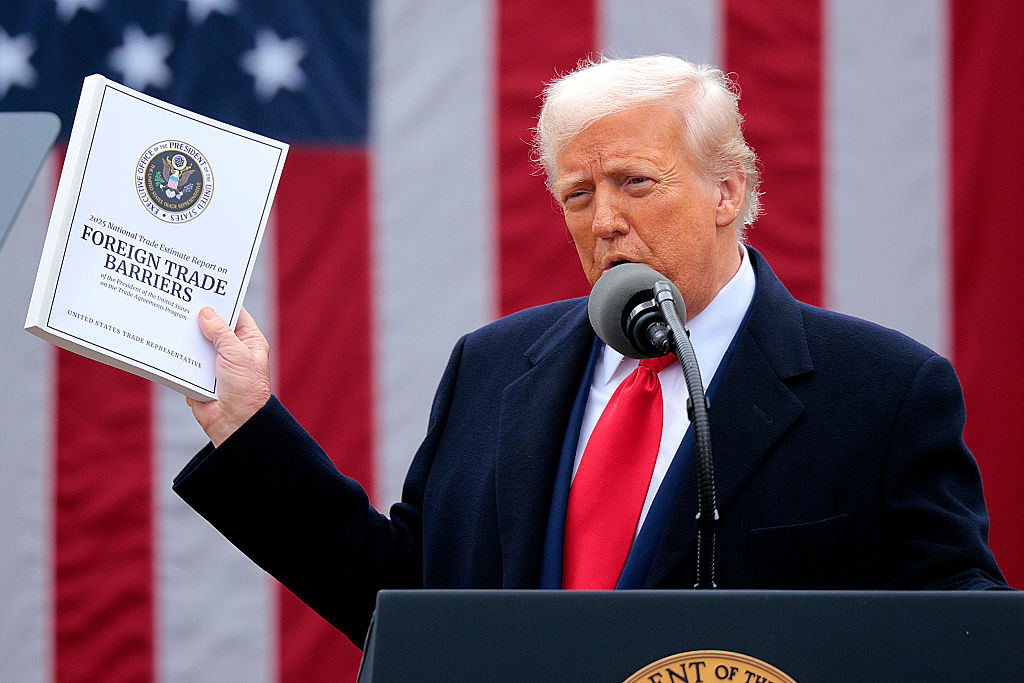

At President Donald Trump’s self-proclaimed “Liberation Day” event on April 2, he waves a 377-page report on “trade barriers” to tout his regime’s increase on tariffs, or import taxes. (Photo: CHIP SOMODEVILLA/GETTY IMAGES)

Share

This article is a joint publication of Workday Magazine and In These Times.

President Donald Trump stood behind a podium in a large clearing of the Rose Garden, American flags hanging vertically between each White House column, to lambast a global trade system in which “our country has been looted, pillaged, raped and plundered by nations near and far, both friend and foe alike.”

It was April 2, which Trump deemed “Liberation Day,” and he was declaring “economic independence” from the rest of the world.

The message was that of an underdog finally standing up against abuse. Workers have “watched in anguish as foreign leaders have stolen our jobs, foreign cheaters have ransacked our factories and foreign scavengers have torn apart our once beautiful American dream,” the president said. “We had an American dream that you don’t hear so much about.”

The headlines were dramatic. “Trump’s tariffs mark the end of an era for free trade in North America,” the Washington Post proclaimed.

But what were the president’s actual grievances? About five minutes into the announcement, Trump started waving what he called a “special book” back and forth, like a prosecutor holding up evidence in a courtroom. The misdeeds against the United States, he said, are “detailed in a very big report by the U.S. Trade Representative.”

The document, the 2025 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers, is a 377-page laundry list of what the United States views as “trade barriers” but what people in other countries might see as legitimate protections and regulations. These barriers, for example, include a bird-flu

food safety measure in Morocco and a requirement in Nigeria that certain imports are certified “safe for human use and consumption.” They also include Canada’s “comprehensive agenda to achieve zero plastic waste by 2030” and Colombia’s requirements that imports of U.S. milk powder meet lactic acid and other quality standards.

The barriers Trump cited in his Liberation Day address are, in many cases, measures that protect working-class people in the United States and around the world.

There is little clarity about the trade deals Trump claims to be pursuing; his administration says he wants to negotiate 90 deals in 90 days. But there is every reason to be concerned he is using tariffs as leverage to advance some of the most coercive aspects of U.S. power: to undermine national sovereignty of other countries, trample on public goods and expand the brute power of the United States and its multinational corporations. Put another way: Behind all the lunch pail rhetoric, antiestablishment posturing and feigned concern for the working class, what Trump is proposing is more heavy-handed, anti-worker, military-driven economic policies.

But the situation is not just “free trade” as usual. It is an agenda to expand corporate power, in the hands of a president who takes coercion to new heights. In the same executive order that established “reciprocal tariffs” on April 2, Trump was explicit about setting up a protection racket. The order states that the United States may decide to reduce tariffs if a country changes its policies to “align sufficiently with the United States on economic and national security matters.”

***

For Trump’s Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR), it’s a problem that South Korea prioritizes domestic technology for its own weapons production. South Korea is a close U.S. ally and hosts 80 U.S. military base sites and nearly 29,000 American troops. Yet, for this administration, South Korea must also keep its doors perpetually open to purchases from the American weapons industry, which is already the largest in the world.

Among the unfair trade barriers that must be torn down, the USTR report says, are “policies that prioritize local technology and products over foreign defense technology.”

Cathi Choi, executive director of Women Cross DMZ, which organizes for peace in Korea, explains that the idea aligns “with all of the vested financial interests in maintaining the forever war in Korea. Weapons manufacturers profit from this war, and it’s everyday people who are losing out.” The Korean War, to which the United States is officially a party, never formally ended, which has led to a dangerous demilitarized zone littered with landmines, as well as perpetual, forced family separations.

The report’s mention of these “defense” barriers is no small thing, as the document provides guidance for trade policy under Trump. “This report lays out both the type of policies and the exact policies that the United States is trying to dismantle around the globe,” says Arthur Stamoulis, executive director of the Citizens Trade Campaign, a coalition of environmental, labor and other civil society groups. It’s “one of the best indicators we have right now of the Trump administration’s trade priorities.”

The annual report typically skews pro-corporate. It’s been published every year since 1985, and the reports have purveyed “free trade” dogma under both Democratic and Republican administrations. But Trump’s national trade estimate is more extreme than in recent years, especially when it comes to opposing big tech regulations, like privacy protections, and pushing back against most anything that would limit profits for the weapons industry. The report reads like a corporate wish list, identifying environmental protections and public health and safety measures as barriers to trade. And Trump is using tariffs as a bludgeon, to force other countries to agree to these demands.

“It’s really the coercion of the tariff threat that’s new,” says Léa Auffret, a Brussels-based leader with the Transatlantic Consumer Dialogue, a network of 76 consumer and digital rights groups.

The 2025 report marks an escalation from previous years when it comes to the U.S. weapons industry, and the barriers to U.S. weapons companies in South Korea it mentioned were never brought up under Biden. The report also charges that measures around the world that limit the purchasing of American arms are barriers to trade, from Brazil’s prioritization of domestic defense manufacturing to Colombia’s requirement of “government-to government agreements for some defense procurements.” In all, there are 62 mentions of “defense” in the 2025 report, up from 29 in 2024 and 33 in 2023. It also mentions more jurisdictions (countries and regions) — 17 in 2025, versus 11 in 2024 and 15 in 2023.

But the USTR is not just protecting American weapons companies. The new report also targets environmental policies, including Thailand’s renewable energy incentive, which “aims to increase biofuel and renewable energy consumption to 30% by 2037.” Climate change poses an immediate existential threat to Thailand: Bangkok is sinking into the sea as ocean levels rise, and the capital could be 40% flooded by 2030, according to the World Bank.

The report also names a European Union plan to reduce deforestation as a trade barrier, as well as an EU regulation to protect public health and the environment from toxic chemicals, including carcinogens. Labor unions supported the regulation, known by its acronym REACH, when it was first implemented in 2007; workers had a stake in ensuring they were not exposed to hazardous chemicals on the job.

It’s not the first time the EU’s chemical regulations have been in the crosshairs of the United States. When the Obama administration tried, in 2013, to negotiate the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, a massive trade deal, the administration also took issue with the EU’s chemical regulations, along with a host of other protections, from “reimbursement of medicines to how we treat food safety,” Auffret recalls. In light of Trump’s national trade estimate report, she is bracing for more.

“When your laws are listed, you’re under pressure,” Auffret says. “It’s a signal from the U.S., ‘We’re watching this issue and we’re going to bring it up and up and up all over again.’ ” Esther Lynch, general secretary of the European Trade Union Confederation, says “there can be no doubt” that the Trump administration is going to use trade deals to undermine protections around the world.

“We are calling on the [European] Commission not to give in to this type of bullying,” Lynch says.

The report lists public health and safety measures, too, as barriers to trade, including higher standards and regulations on vehicle safety in Japan, Taiwan and Egypt. Egypt has one of the highest rates of deadly road traffic accidents in the world, killing around 12,000 people a year.

The so-called barriers continue into, for example, price caps on coronary stents and knee implants in India. The report also identifies the Indian Patents Act that imposes limits on frivolous patents, which thereby helps ward off pharmaceutical monopolies, as a barrier. This law helps keep the cost of medicines down in a country where 7% of the population—or 100 million people — are thrown into poverty every year because of healthcare spending.

K.M. Gopakumar is a New Delhi-based legal advisor and senior researcher with the Third World Network, which promotes just and sustainable development in the Global South. He says this language is concerning, because “price control offers an important tool to protect people from the exploitation of commercial actors.”

When it comes to the regulation of big tech, Trump’s report has more corporate giveaways to “commercial actors” than the Biden administration. Trump’s USTR identifies “digital trade barriers” in 35 countries plus the European Union, and takes aim at the regulation of artificial intelligence, privacy protections and digital services taxes, which allow countries to tax big tech companies that aren’t physically located within their borders. “In essence, President Trump has declared a trade war on countries who have the temerity to regulate Big Tech in the interests of their people,” Public Citizen, a watchdog organization, asserted in a statement.

The 2024 report recognized that countries have “a sovereign right to adopt measures in furtherance of legitimate public purposes,” wording that had given some social justice organizations hope that the USTR, under Katherine Tai, would take a different tack. Melinda St. Louis, the director of Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch, says, “Last year’s report under President Biden had a more nuanced approach, removing a number of public interest laws from the list. But now they’re back in.” Canada’s policy to decrease plastic waste, for example, was included in 2022 but then omitted in 2023 and 2024. Now it’s back.

The very concept of a “non-tariff barrier” to trade has been used since the Nixon administration as a euphemism for steamrolling basic public goods and regulations to make way for corporate profits, David Dayen points out in The American Prospect. Stamoulis, of the Citizens Trade Campaign, is concerned that the concept is now at the center of Trump’s trade policy. “This is the most powerful country on Earth dictating what governments are and aren’t allowed to do to protect the health and well-being of their populations on a day-to-day basis,” he says. “This impacts food safety, access to medicine, online safety. Real stuff with real life-and death consequences.”

***

On Liberation Day, Trump announced a 10% baseline tariff on all countries, as well as dramatically steeper “reciprocal tariff ” rates for dozens of countries from South Korea to Taiwan to China. The steeper rates were soon suspended for 90 days, except on China, to allow Trump to negotiate trade deals — an open strategy to use tariffs as a stick to extract concessions. (Though on May 12, the United States reached an agreement to temporarily reduce its tariffs on China to 30%, while China cuts its import duty to 10% on U.S. goods.)

We already know that Trump has a propensity toward using tariffs to reward friends. He did so during his first term, when he imposed tariffs on some imports from China in 2018, yet granted exemptions to donors and associates. A 2024 study in the Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis found that companies had a 1 in 5 chance of getting an exclusion from the tariffs if they had donated to Republican candidates, versus a 1 in 10 chance if they had given to Democrats.

There is reason to think that this trend is continuing into the present. ProPublica found that firms with political connections, or those that heavily lobby the Trump administration, “might be winning carve-outs” from sanctions. And the Washington Post found that, amid tariff trade talks, U.S. embassies and the State Department are pressing countries to license with Starlink, the satellite internet company owned by Elon Musk, Trump’s powerful associate and largest donor.

The Liberation Day tariffs are far more sweeping than any in Trump’s first term, and any concessions will be extracted at gunpoint.

The guns are not just metaphorical. There are signs that Trump will try to use tariffs, or trade more broadly, to fortify the U.S. military, which is by far the most heavily funded on the planet, with an estimated 750 military bases around the globe. Bloomberg reported April 21 that Trump has “raised the financial contribution Tokyo makes to support U.S. military bases in Japan as an issue of concern, including before a meeting with Japanese trade negotiator Ryosei Akazawa last week.” (There are at least 50,000 U.S. troops stationed in Japan, where U.S. military bases have faced local protests for decades over environmental pollution, sexual assaults and other issues.)

“China is clearly the number-one target of these tariff policies,” says Lindsay Koshgarian, program director for the National Priorities Project, which produces research about military spending. “Diplomatic relationships between the U.S. and China have fallen apart. This is a key ingredient setting us up for actual military conflict.”

In response to the “reciprocal tariffs,” China is stepping up its own efforts to cultivate trade and investment deals with other countries, a move that could ultimately weaken the U.S. empire. But even this tit for tat has consequences. “This is the classic Cold War arrangement of lack of diplomacy and aligning countries against each other,” says Koshgarian. “There’s the possibility not just of direct war, but proxy wars and military buildup.”

Trump has used tariffs to bolster other violent aspects of the U.S. security state. Even before declaring Liberation Day, he used the threat of tariffs to press countries into participating in his imprisonment and deportation of immigrants, or escalating their own border militarization. In January, for example, Trump successfully used the threat of tariffs to pressure Colombia into accepting flights of deported migrants. (Colombia had initially resisted to protest the administration’s poor treatment of migrants.) In February, Trump threatened tariffs unless Mexico deployed its military to parts of the border with allegedly high rates of border crossing.

Trump already has one major domestic policy proposal we can review to understand his trade priorities. His proposal of a $1 trillion military budget is the most bloated domestic industrial policy we have in this country (and is actually higher when militarized spending in other budgets is included). Every year, around half of the military budget goes to military contractors like Lockheed Martin and General Dynamics, which are manufacturing the bombs being dropped on Yemen and Gaza or loaded onto the warships encircling China.

In turn, Trump’s USTR does the bidding of the U.S. weapons industry, giving countries black marks for measures limiting U.S. weapons industry profits.

“I think what we’re witnessing is an embrace of all the tools of U.S. imperialism,” says David Vine, a political anthropologist and author of Base Nation: How U.S. Military Bases Abroad Harm America and the World. According to Vine, we are seeing this imperial bent with Trump’s territorial claims, “threatening to invade and seize Greenland,

Gaza, Canada, Panama.

“He is embracing forms of economic imperialism that certainly have been part of past administrations, but he’s embracing them in profoundly broader ways and deeper ways.”

No doubt, capital was not happy with Trump’s announced reciprocal tariffs. The stock market tanked near bear market territory, and millionaires and billionaires took the rare step of speaking out against Trump’s policies. But just because the CEOs of JPMorgan Chase and BlackRock vocally denounced them doesn’t mean they’re somehow a bulwark against the excesses of capital; the pushback likely came against uncertainty, day-to day volatility and caprice, rather than against the ultimate goal of maximizing American corporate power.

“Trump is trying to use the failures of the system to win workers’ votes,” says Manuel Pérez-Rocha, an associate fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies, who has spent nearly three decades researching trade. “But workers are being defrauded.”

There is a debate to be had about the role sectoral tariffs could play in a larger industrial policy to protect wages and working conditions. United Auto Workers, for example, has argued in favor of certain tariffs and even praised Trump’s auto tariffs in late March, parting with the Canadian auto union Unifor. Labor journalist Luis Feliz Leon has suggested there are more internationalist frameworks for labor to take up, like cross-border coordination focused on protecting workers throughout corporate supply chains.

But perhaps Trump’s reciprocal tariffs are not, functionally, tariffs at all. As David Dayen argued in The American Prospect on April 3, they’re best understood as sanctions, “only he’s doing it against the whole world, all at once, for the assumed harm of ‘ripping off ’ the United States for decades.”

As Dayen wrote: “It is no different from a mob boss moving into town and sending his thugs to every business on Main Street, roughing up the proprietors and asking for protection money so they don’t get pushed out of business.”

One major thing Trump’s tariffs have in common with sanctions: On Liberation Day, Trump invoked the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 as the authority for his reciprocal tariffs. For decades, the act has been used by presidents to impose sweeping— and devastating — economic sanctions on countries from Venezuela to Cuba to Iran to Vietnam. Before Trump took office, it had been used by presidents 69 times, according to the Congressional Research Service, and it “sits at the center of the modern U.S. sanctions regime.”

But there are also key differences. Sanctions are framed as punitive against “enemy” countries, whereas reciprocal tariffs are ostensibly aimed at trade relations with the entire world. And they are being used against U.S. allies, raising questions about whether Trump is pursuing empire in traditional terms, by expanding spheres of American influence.

Whether or not reciprocal tariffs constitute formal sanctions, Trump is using them (or the threat of them) as a cudgel against other countries in what appears to be a bid to project American strength. They should be viewed as part of a longer history of the United States using economic pressure to achieve might. Even should Trump ultimately be bluffing, his bluffing has tremendous economic and policy implications, as we are seeing with the global frenzy to respond to tariff threats. This is true even as U.S. courts question the fundamental legitimacy of the “Liberation Day” tariffs, with the chance that they could be overthrown for good, though the Trump administration is digging in its heels.

Does this moment mark a break from neoliberalism, or an intensification of it? Are we closer to a 19th– or 20thcentury colonialism, or a more modern form of economic nationalism coupled with imperialism? Trump himself has been erratic: He has presented himself as a defender of American workers despite waging an unprecedented war on the basic rights of workers to collectively bargain, meanwhile gutting public programs for the poor at a headspinning pace. He bemoans the free trade system while embracing its most destructive components, such as opposition to public health, environmental protections and welfare programs, and his own renegotiation of NAFTA during his first term ended up being a huge disappointment for workers. And there are reasons to think there are divisions within the Trump administration, as Elon Musk parts with Trump on tariffs while some advisors, like Peter Navarro, double down.

Ultimately, it’s not rhetoric or buzzwords that are important, but the material policies the most powerful person on Earth is advancing. And while it is difficult to know what is going on in the president’s psyche, there is a consistent throughline that runs throughout his actions: marrying trade and militarism as a means to undermine other countries’ sovereignty and democratic decision-making, and projecting an image of American strength that is rooted in violent domination and the erosion of the welfare state.

On Liberation Day, Trump stood on the Rose Garden lawn and called out “American steelworkers, auto workers, farmers and skilled craftsmen, we have a lot of them here with us today. They really suffered gravely.” And they have, in the United States and around the world, due to decades of pro-corporate measures that have battered workers and left them without basic protections.

It’s a trend Trump is by no means reversing, but escalating — complete with new, faux-populist branding — at a breakneck pace.