Share

Editor’s note: In the 1880s, Eva McDonald Valesh wrote a series of newspaper articles exposing the horrible conditions facing women working in a Minneapolis garment factory. This article originally appeared in the Union Advocate newspaper as part of its centennial series in 1997.

In 1888, the Knights of Labor in Minneapolis and St. Paul turned their attention to the growing number of working women in the cities. Locally, they noted, working women were underpaid and overworked. They were the victims of economic conditions which forced them to work for low wages.

The committee investigating the conditions reported that “It is an absolute certainty that no power will intervene between the employer and his female help to increase wages unless the working girls are able to make the demand for higher wages themselves and enforce it. This can only be done, and will be done, at the present time through organization. Organization, then, is the first duty of the hour, and this must be brought about by girls who are already organized.”

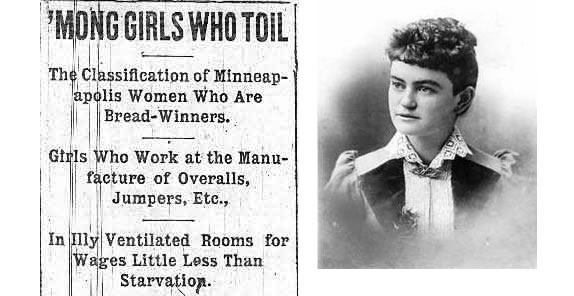

The same month that the report was published, Eva McDonald, the daughter of a workingman and a member of the Knights, began to publish a series of stories on working women in the St. Paul Globe. Her first story, “Among Girls Who Toil,” covered the horrible conditions of women working in a Minneapolis garment factory. Within two weeks, its women workers went on strike after the firm cut their wages. Eva McDonald was among those leading and reporting on the strike. The coming together of Knights and workingwomen gave support to the first women’s strike in the Twin Cities. It also gave a tremendous start to the career of journalist and labor activist Eva McDonald Valesh.

Eva McDonald was born in Maine in 1866 of John and Elinor Lane McDonald, Canadian immigrants of Scotch-Irish descent. At the age of 12, McDonald moved with her parents to the Twin Cities. After high school, she took some teacher training courses. Turned down for a teaching position because she was “too young,” McDonald trained as a typesetter. Soon after, she took the job as a journalist for the Globe. Her series on working women was followed by articles on organized labor. From 1891 to 1896, she worked as a political reporter and labor editor for the Minneapolis Tribune.

Mentored by leaders

Throughout this period, Eva McDonald was mentored in public speaking and political economy by local labor radicals and populists, including John McGaughey, master workman of the Knights’ district assembly; Timothy Brosnan, his successor; and Ignatius Donnelly, a politician turned populist. With their support, McDonald traveled across Minnesota and the country as a public speaker for labor and populist causes. She ran for the local school board in 1888. She became a state lecturer for the Minnesota Farmers’ Alliance, and later served as a national delegate to labor conventions. McDonald also published work on labor and political economy in national journals, such as the Journal of United Labor, National Economist, Railway Times and the American Federationist, the monthly publication of the American Federation of Labor.

These writings gave her a national reputation. Annie Diggs, the populist writer, saw McDonald as a “comet” streaking across the skies of American reform politics. Kate Donnelly, who thought her husband was overshadowed by the younger woman, described her as “a vicious pest.” Still others saw McDonald as a “Joan of Arc” for the laboring classes, a woman who would help lead workingmen and women to fight for a better life.

In 1891, Eva McDonald married another rising star in Minnesota labor politics, cigarmaker and trade unionist Frank Valesh. Frank Valesh was a Czech immigrant, who came to the states when he was 14. Well-read in labor thought, Frank Valesh had become in his twenties a protege of Samuel Gompers, the new head of the American Federation of Labor. He and Eva McDonald were among the co-founders of the Minnesota Federation of Labor in 1890.

Marriage of equals

Their marriage was a marriage of equals. And their collaboration in state labor politics led to the appointment of Frank as assistant commissioner of labor and an officer in the state federation; it also aided Eva’s career in journalism. The two went on a tour of Europe in 1896. Their labor credentials, and the patronage of Samuel Gompers, opened doors to European trade union leaders. Eva McDonald’s reports were published serially in the American Federationist. The couple seemed on their way to success.

Part of the reason for the European trip, however, was Frank Valesh’s fragile health, as he began to show the first signs of tuberculosis, which led to his death in 1916. Frank’s illness seemed to get better through the European trip. After his return, however, Frank retired from labor circles to the town of Graceville, Minn., where he opened a cigar factory. Frank and Eva separated and Eva assumed custody of their only child, Frank Morgan Valesh. They divorced in 1906.

After her separation from Frank, Eva McDonald Valesh pursued a career in journalism in New York (where she worked for William Randolph Hearst’s New York American) and in Washington, D.C. She eventually accepted a position as assistant editor of the American Federationist. She served as Gompers’ office assistant, handling journal business and writing articles on child labor, citizenship, and working women; she also worked as an organizer and public speaker. In 1910, Valesh left the AFL. The reasons aren’t entirely clear, but in later years she told an interviewer that she felt unappreciated and that Gompers had refused to acknowledge the importance of her work. She went on to edit a magazine for a women’s club involved in reform activities and later became a proofreader for the New York Times. She worked at the Times for 25 years, retiring shortly before her death in 1956 at age 90.

Over the course of her career, Eva McDonald Valesh was witness to many changes in the labor movement. She began as a labor radical in the Knights of Labor. She later adopted the values of “bread and butter unionism” when she worked with the Samuel Gompers in the American Federation of Labor. She was a woman pioneer in labor organizing and in the promotion of women’s labor activism. Throughout her career, Eva Valesh wrote sensitively of the plight of women workers. She was a popular speaker on the subject. In her lectures, she sought first to convince working women to organize. Valesh wrote, “The American Federation of Labor is the body best fitted to investigate women’s work and apply the proper remedy for existing abuses.”

During much of her career, Eva McDonald Valesh celebrated the potential of the labor movement for “ethical influence” and the strength of its “bonds of brotherhood,” even as she understood labor did not always live up to its promise of equality for women workers. In these sentiments and others, Eva McDonald Valesh was representative of the labor values of her age.

Elizabeth Faue is an associate professor of labor history at Wayne State University in Detroit. She is the author of “Community of Suffering and Struggle: Women, Men and the Labor Movement in Minneapolis, 1915-1945” and a biography of Eva McDonald Valesh, “Writing the Wrongs: Eva Valesh and the Rise of Labor Journalism.”

Articles by Eva McDonald Valesh

‘The Toiling Women’