Share

The past 12 months of the global pandemic has led to entire industries shutting down, shifting, downsizing, and otherwise attempting to adapt to different expectations and protocols. While there are many different studies that highlight the issue of job security for women during the pandemic, the numbers overwhelmingly show a much starker reality for women of color, who already face an array of barriers including discrimination, structural racism, and bias. Unfortunately, new data indicates that these issues have been exacerbated by the pandemic.

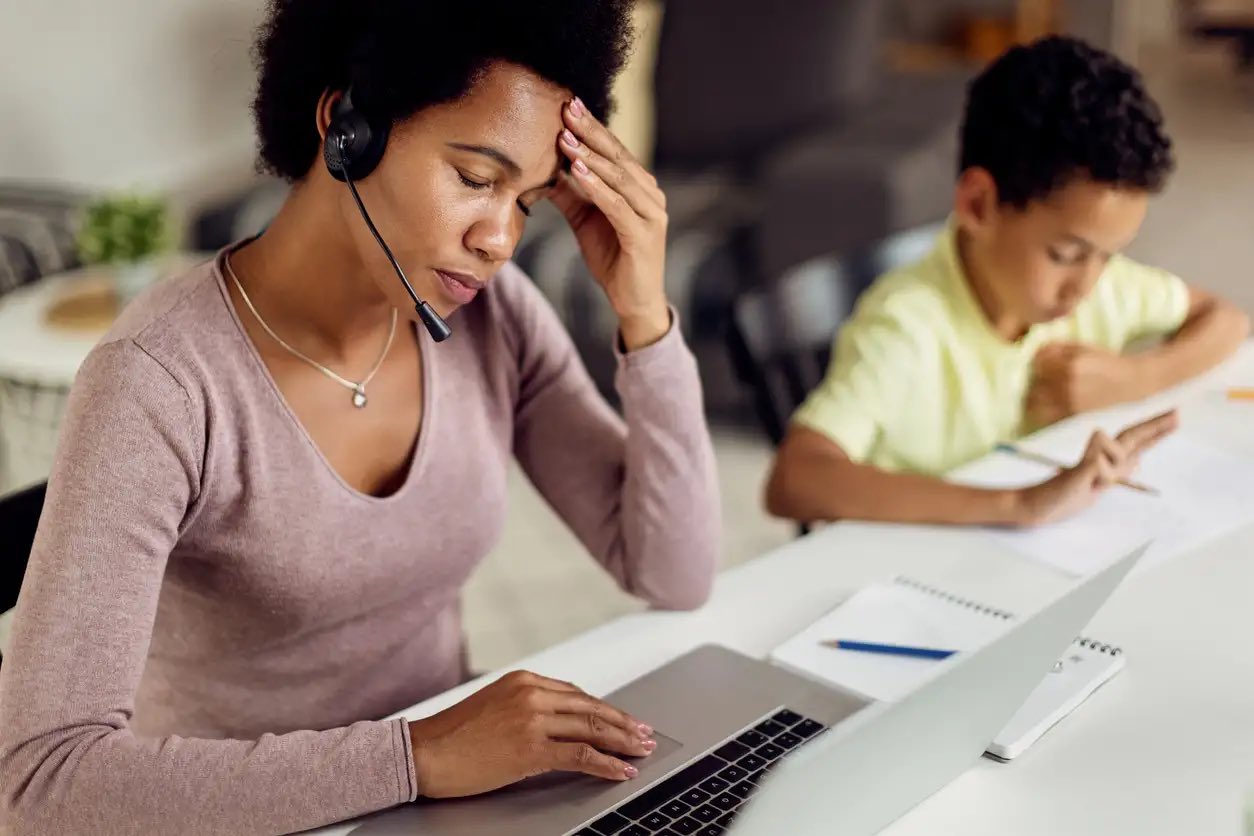

Statistically, women are 1.8 times more vulnerable to the pandemic than men, due in part to the increased burden of child care, which is still disproportionality carried by women. Additionally, women globally account for 75% of the world’s total unpaid care work which includes child care, elder care, and household duties such as cooking and cleaning. In the U.S., the hours spent on family responsibilities for women has increased by up to two hours. A recent study shows that before the pandemic, women in the U.S. made up 46% of the workforce, but unemployment data suggests that women now make up 54% of unemployment in the aftermath of the pandemic. Women’s employment has dropped at an alarmingly faster rate than average, even though data suggests men and women work in different sectors. The numbers are even starker for Black, Latinx, and women of color compared to white women.

In order to understand the aftershock of the pandemic for women of color, it’s essential to examine the underlying issues that existed well before COVID-19. Being a caregiver in the U.S. can be expensive for women as they typically spend $15,000 on both direct and indirect caregiving-related expenses in their lifetime. More than half also are frequently required to take time off from work to tend to their caregiving responsibilities. Unfortunately, this translates into a monetary cost for women with a lost amount of income and career opportunities to move up. If women leave work early to care for their children, they are seen as not focused on their work, which has repercussions when it comes time for promotions, travel opportunities, or any after-work meetings with clients. The same risks and challenges to maintaining a work-life balance have not been placed on men in the same way, nor with the same repercussions.

The picture is even starker for women of color, especially Black and Latinx women, who were managing a heavier load of responsibilities than white mothers at work and home even before the pandemic. Black and Latinx women are more likely to be their family’s sole breadwinner or to have their partner working outside their home in an essential service role during the pandemic. They are doing more work at home, too. Latinx mothers are 1.6 times more likely than white mothers in being responsible for child care, and Black mothers are twice as likely to be managing all their family’s care needs.

While many of these studies look at how the pandemic has affected women as a whole, most only momentarily highlight how Black, Native, and other women of color are and have been affected. For Asian American women, there has been a significant increase in unemployment fueled by their strong presence in sectors such as hospitality, leisure, and retail where they make up one in four employees. Even amongst Asian American women in different sectors, data seems to show that of those who are married, they still make less than their spouse. Work-from-home measures have caused women to take on a larger role in child care, housework, and elder care, and pushed Asian American women to exit the workforce, since their partners are more likely to have higher incomes. Others have cited that an additional stressor on Asian American women is the increase in discrimination against Asian Americans with the coronavirus being touted by politicians and pundits alike as being a “Chinese virus.” With hate crimes increasing in across major cities across the U.S. by 150% in the last year, discrimination clearly is playing a role in unemployment for Asian Americans; however, more data is required to better understand these trends in relation to unemployment.

Prior to the pandemic, for every 100 men promoted to a manager position, only 85 women were; for Black women the number was 58, and for Latinxs it was 71. With only Black and Latinx women highlighted in this study, it’s apparent that the problem is much more severe for women of color as a whole than white women. Black women have disproportionately dealt with issues related or caused by COVID-19 as well. They are more than twice as likely as women overall to consider the death of a loved one to be one of their biggest challenges during the pandemic. This, along with increased incidents of racial violence and current political discourse, has required heavy emotional labor from them. Their workplaces have not been understanding or cognizant of how these issues may have affected them, before or during the pandemic. Black women reportedly get substantially fewer inquiries from their manager about their workload and work-life balance than other women. Additionally, fewer than one in three Black women report that their direct manager has checked in on them in light of recent racial violence or made any changes to foster a more inclusive work culture on their teams or in their work environments. These issues have had a severe impact on Black women who are more reluctant to share their thoughts on racial inequities due to several factors, including that they often feel more excluded at work.

While 61% of white men and 65% of white women colleagues of women of color say that they are allies to women of color, the reality is quite different. Studies have shown that only 12% of white women and 8% of white men actively mentor women of color, and that only 42% of senior-level white men even listen to women of color on issues of bias or racism, compared to 63% of white women. Across the board, white men are less likely to give credit to women of color at work or actively attempt to confront discrimination when they see it happen. With a workforce that has been so stifling for Black women, Indigenous women, and other women of color, it’s no shock that they have suffered at the hands of the same behavior magnified during the pandemic.

Despite multiple studies that prove that both gender and racial diversity brings in greater returns to shareholders, increases innovation, and results in more agile and effective teams, in many sectors there’s still resistance to diversity and inclusion (D&I) initiatives and departments, which are often up on the chopping block when budgets are slashed. According to McKinsey, a management and consulting firm, even organizations that did have robust D&I initiatives reported that 27% of them have put all or most of their initiatives related to D&I on hold due to the pandemic.

This is a global phenomena. Regardless of where those countries were before the pandemic on working toward gender equity, all of their economies have been affected by the unpaid burden of child care resulting from the pandemic. Between the two genders identified in the McKinsey study, women make up 39% of the global economy and bear the burden of accounting for 54% of job loss. If the current trends continue as is and remain unchecked by both the private and public sectors, it is estimated that global GDP growth could be $1 trillion dollars lower by 2030 if women continue to bear the brunt of this particular kind of economic disenfranchisement.

The trends of the global economy largely dictate the trends of each country’s economic health both during the pandemic and in the world we’ll be walking into after. When there are global trends of this size, understanding and remedying them must be factored into how economies plan their COVID-19 recovery strategies. If the pandemic is a portal, then we’ve found ourselves time traveling several decades into the past when it comes to equity for women of color. What will define our economy is the role that women, particularly women of color, will have in it. Without active strides toward remedying this alarming national trend, we may find ourselves in a very different world than the one we’ve been working toward.