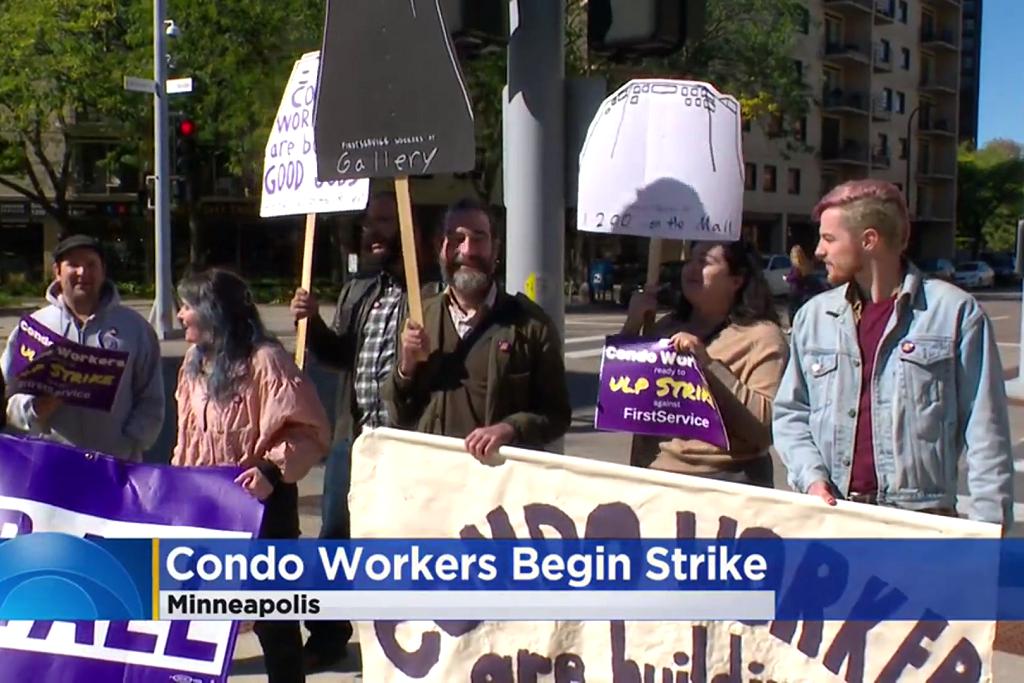

Condo workers for FirstService Residential across the Twin Cities demonstrated in Minneapolis in October 2022.

Share

This article is a joint publication of Workday Magazine and The American Prospect.

Michael Rubke, a desk attendant at La Rive condo complex in Minneapolis, is fighting for a union against a behemoth building management company, FirstService Residential of Minnesota, that has a near-monopoly on high-rise condos in the Twin Cities. It’s been a difficult battle so far. The unionization campaign is “at square one,” the 41-year-old explained over the phone after working an overnight shift. “They’re pretending we’re not there.”

But that lack of formal union representation did not stop Rubke and his colleagues throughout the Twin Cities from fighting for—and winning—statewide legislation this summer that improves the terms of their jobs, by beating back a little-known provision used to erode the job security of contracted workers.

Under the legislation, which went into effect on July 1, companies in Minnesota are barred from entering into new contracts that contain restrictive covenants, which function like noncompete agreements but have previously slipped past the prohibitions on noncompetes in Minnesota because they have a slightly different structure. Existing restrictive covenants, however, are left in place.

“It’s a damn victory. It’s wonderful,” says Rubke. “There is still work to be done. We can always improve things for the working class. But this is a big victory. We should all be happy about it.”

These restrictive covenants are made between contracted companies and their customers, often without the knowledge of the workers themselves. The provisions restrict the ability of workers to freely sell their labor, even though they are not party to the contract.

In Rubke’s case, FirstService Residential and the homeowners association have an agreement that if FirstService Residential stops providing building services, the condo can’t hire Rubke or any other desk attendants or caretakers—either directly or through a competing building management company—for at least a year. Such agreements mean that if a homeowners association wants to dump their building management company, they will lose the building’s beloved employees, some of whom have been there for years and have unique knowledge of how to fix that flickering light, where to put special packages, or which residents like to stop and chat. Such a provision reduces the incentive for homeowners associations to change contracts, and gives more leverage to companies like FirstService Residential, which can knuckle down wages or benefits.

“It’s two people who aren’t me deciding where I can work in the future,” Rubke says. “I’m left out of that, and it’s kept a secret.”

NONCOMPETE AGREEMENTS, WHICH EXIST in contracts with workers themselves, are falling out of favor. The Federal Trade Commission recently finalized a rule to ban them in most cases, and the rule is set to go into effect September 4, though it faces business lawsuits. Minnesota banned new noncompete agreements in 2023 (while leaving existing ones in place), thanks to the advocacy of workers, including some from FirstService Residential. And even FirstService Residential publicly said it would stop enforcing existing noncompetes against hourly workers in Minnesota after the company received negative press for how it treated a live-in caretaker who had been active in union organizing efforts.

But restrictive covenants are a back door to traditional noncompetes, and they affect a stratum of highly exploited low-wage workers: contracted laborers. They are part of the architecture of increasingly fissured workplaces, where workers are employed by intermediaries, which deprive them of basic job protections. What makes this legislative win so significant is that it’s part of a small but growing effort to close that back door.

Lev Roth, 38, has been working at Riverview Tower in Minneapolis for five years. “I really like working with residents,” they say over Zoom. “There are a lot of interesting, cool people.” Because the building is owner-occupied, they’ve been able to build long-term relationships with some of the people who live there. One even invited Roth to be in her wedding party this coming fall.

In their role, Roth has developed the kind of specialized knowledge it takes years to build. “I know how to fix the elevators when they get stuck,” Roth says. “I have memorized where the keys are. I memorized the layout of the building, and it’s a bit of a labyrinth.”

As far as they know, Roth, too, is subject to a restrictive covenant as an employee of FirstService Residential. “I was really disappointed,” they say, “that we just had this victory and there were no more noncompetes, only to find out that not only was I under a restrictive covenant, but no one had an obligation to tell me before this law was passed.”

According to Dan Mendez Moore, organizer-director with SEIU Local 26, the union and workers had no idea they were subject to such an arrangement until this author’s April 2023 article about restrictive covenants, published in Workday Magazine and The American Prospect. (That article received reporting assistance from Max Nesterak of the Minnesota Reformer.)

Following that discovery, Roth and their colleagues have been active in efforts to pass the ban. Starting in January, workers—and some residents—began testifying to the Minnesota legislature, with organizing support from SEIU Local 26, which has been working to unionize Twin Cities FirstService Residential workers since the winter of 2022.

As a result of this advocacy, Minnesota Rep. Emma Greenman took up the cause, and the legislation made it through the state legislature, then was signed by Gov. Tim Walz earlier this summer. The new rule bans restrictive covenants in any contract signed on or after July 1, with some exemptions. For contracts signed before July 1, the restrictive covenant still applies, but companies have to disclose it to workers.

The legislation is similar to another law in New Jersey that went into effect in October 2023, a legislative win by SEIU 32BJ.

Jonathan Harris, associate professor of law at LMU Loyola Law School in Los Angeles and senior fellow at the Student Borrower Protection Center, says Minnesota’s ban “is an indication that state lawmakers are keeping an eye on employers that are trying to find work-arounds to noncompete bans. They need to be conscious of this whack-a-mole problem, because as soon as noncompete bans started getting traction, we saw management attorneys are advising their client base that they should consider other kinds of contracts that have the same effect of keeping workers unable to shift jobs, but are not classic noncompetes.”

Harris notes, however, that there are other similar provisions that might not be stopped by this bill; for example, “no-poach agreements between separate companies that say, ‘We agree with each other that we won’t hire your employees.’”

THERE ARE ALREADY SOME SIGNS that the ban is forcing the company to be more transparent. In June 2023, before the ban, FirstService Residential high-rise condo workers asked the company to disclose restrictive covenants, but the company refused. However, on July 18, 2024, following the implementation of the ban, the company relented to a follow-up request. Its response: You’re all under restrictive covenants.

According to the FirstService Residential letter, reviewed by Workday Magazine and The American Prospect, the restrictive covenants include clear language restricting workers’ job opportunities: “The Association recognizes the importance and value of Agent’s employees to its business and agrees to refrain from hiring, directly or indirectly (such as by means of a competing management company), any person who is or was employed by Agent during the term, and for one year following the term, of this Agreement, regardless of the reason for the termination.”

Workers do not think the company’s response is adequately transparent. They want to see every contract with every building affected by a restrictive covenant. It’s unnerving, they say, to still not have seen the specific language that constrains their freedom of employment. Workers are unclear, further, how restrictive covenants affect employees at midsize townhomes in the Twin Cities area, which FirstService Residential provides services for.

The concern is not theoretical. While FirstService Residential has long provided building services to a vast majority of high-rise condos in the Twin Cities, that is starting to shift. FirstService Residential has seen a 25 percent reduction in its high-rise condo portfolio since 2020, according to SEIU Local 26.

In August 2023, when the River Towers switched to the contractor Sudler Property Management, FirstService Residential threatened to enforce its restrictive covenant and put its employees out of work. But following a pressure campaign by workers and residents, FirstService Residential relented, agreeing to allow employees to keep working at River Towers under Sudler, though by then some workers had been transferred to other FirstService Residential properties.

Four more FirstService Residential properties have switched building management companies in recent months. Moore says that since it was clear the ban was going to pass, the union knows of no instances where FirstService Residential enforced existing restrictive covenants. This could be a sign that the company has deemed these provisions too troublesome to enforce. FirstService Residential has not responded to a request for comment.

However, the very existence of the restrictive covenants can do harm: Moore says that some workers have quit their jobs over concerns about how the restrictive covenants might affect them. For their part, Roth was so disappointed to learn they were working under a restrictive covenant that the legislation banning new agreements “hardly feels like a victory. It just feels like the next step. It won’t feel like it’s a victory until this law is nationwide.”

Workers say that FirstService Residential should release them from all existing restrictive covenants now, rather than making them wait for their contracts to expire. “I’m still under a restrictive covenant,” says Rubke, “and if I lose my job, I would still have to deal with the consequences of a restrictive covenant I didn’t know about.”

“I do think it’s important to note that these shadow noncompetes, they don’t just negatively affect people who work there,” he adds. “This is also a way the company I work for bullies the people who they’re supposed to be working for. FirstService Residential has been using those as a way to bully HOAs and residents.”

Rubke describes his job as “quiet.” As an overnight worker, he says he is tasked with being “ready and available in case something happens”: a water pipe bursting, a medical emergency, a resident who needs something.

When he’s not working, he says, he likes to play guitar and write music. “I’m hoping to record some songs soonish, just to get them out of my head.” He likes to spend time with friends, he says, and he is “pretty good at trivia at the bar on the weekends.”

A union, he hopes, could give workers “a bit more control over our lives.” SEIU Local 26 has filed multiple unfair labor practice lawsuits, and has waged strikes against the company. “We’re not union yet, we’re still working on it,” he says, “but we’ve had some cool victories along the way.”

Note: FirstService Corporation, based in Toronto, is the parent company of FirstService Residential, and FirstService Residential of Minnesota is part of FirstService Residential. For ease of reading, we give the full name, FirstService Residential of Minnesota, at first mention, but after that refer to it in shorthand as FirstService Residential.