A female doctor therapist in a white robe, mask and gloves. Face close-up. The doctor cries and prays. Tears in eyes. Regret, anxiety and despair. Pandemic and virus epidemic. Coronavirus covid-19.

In states like Minnesota, there is need for health care professionals to help fight COVID-19, but hospitals are losing out on other forms of revenue, which has led to staffing cuts. (Adobe Stock)

Share

This story was originally published by ProPublica. ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

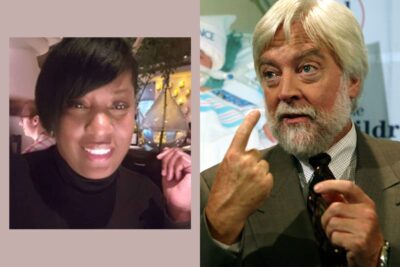

When police discovered the woman, she’d been dead at home for at least 12 hours, alone except for her 4-year-old daughter. The early reports said only that she was 42, a mammogram technician at a hospital southwest of Atlanta and almost certainly a victim of COVID-19. Had her identity been withheld to protect her family’s privacy? Her employer’s reputation? Anesthesiologist Claire Rezba, scrolling through the news on her phone, was dismayed. “I felt like her sacrifice was really great and her child’s sacrifice was really great, and she was just this anonymous woman, you know? It seemed very trivializing.” For days, Rezba would click through Google, searching for a name, until in late March, the news stories finally supplied one: Diedre Wilkes. And almost without realizing it, Rezba began to keep count.

The next name on her list was world-famous, at least in medical circles: James Goodrich, a pediatric neurosurgeon in New York City and a pioneer in the separation of twins conjoined at the head. One of his best-known successes happened in 2016, when he led a team of 40 people in a 27-hour procedure to divide the skulls and detach the brains of 13-month-old brothers. Rezba, who’d participated in two conjoined-twins cases during her residency, had been riveted by that saga. Goodrich’s death on March 30 was a gut-punch; “it just felt personal.” Clearly, the coronavirus was coming for health care professionals, from the legends like Goodrich to the ones like Wilkes who toiled out of the spotlight and, Rezba knew, would die there.

At first, seeking out their obituaries was a way to rein in her own fear. At Rezba’s hospital in Richmond, Virginia, as at health care facilities around the U.S., elective surgeries had been canceled and schedules rearranged, which meant she had long stretches of time to fret. Her husband was also a physician, an orthopedic surgeon at a different hospital. Her sister was a nurse practitioner. Bearing witness to the lives and deaths of people she didn’t know helped distract her from the dangers faced by those she loved. “It’s a way of coping with my feelings,” she acknowledged one recent afternoon. “It helps to put some of those anxieties in order.”

On April 14, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published its first count of health care workers lost to COVID-19: 27 deaths. By then, Rezba’s list included many times that number — nurses, drug treatment counselors, medical assistants, orderlies, ER staff, physical therapists, EMTs. “That was upsetting,” Rezba said. “I mean, I’m, like, just one person using Google and I had already counted more than 200 people and they’re saying 27? That’s a big discrepancy.”

Rezba’s exercise in psychological self-protection evolved into a bona fide mission. Soon she was spending a couple of hours a day scouring the internet for the recently dead; it saddened, then enraged her to see how difficult they were to find, how quickly people who gave their lives in service to others seemed to be forgotten. The more she searched, the more convinced she became that this invisibility was not an accident: “I felt like a lot of these hospitals and nursing homes were trying to hide what was happening.”

And instead of acting as watchdogs, public health and government officials were largely silent. As she looked for data and studies, any sign that lessons were being learned from these deaths, what Rezba found instead were men and women who worked two or three jobs but had no insurance; clusters of contagion in families; so many young parents, she wanted to scream. The majority were Black or brown. Many were immigrants. None of them had to die.

The least she could do was force the government, and the public, to see them. “I feel like if they had to look at the faces, and read the stories, if they realized how many there are; if they had to keep scrolling and reading, maybe they would understand.”

It’s been clear since the beginning of the pandemic that health care workers faced unique, sometimes extreme risks from COVID-19. Five months later, the reality is worse than most Americans know. Through the end of July, nearly 120,000 doctors, nurses and other medical personnel had contracted the virus in the U.S., the CDC reported; at least 587 had died.

Even those numbers are almost certainly “a gross underestimate,” said Kent Sepkowitz, an infectious disease specialist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City who has studied medical worker deathsfrom HIV, tuberculosis, hepatitis and flu. Based on state data and past epidemics, Sepkowitz said he’d expect health care workers to make up 5% to 15% of all coronavirus infections in the U.S. That would put the number of workers who’ve contracted the virus at over 200,000, and maybe much higher. “At the front end of any epidemic or pandemic, no one knows what it is,” Sepkowitz said. “And so proper precautions aren’t taken. That’s what we’ve seen with COVID-19.”

Meanwhile, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reports at least 767 deaths among nursing home staff, making the work “the most dangerous job in America,” a Washington Post op-ed declared. National Nurses United, a union with more than 150,000 members nationwide, has counted at least 1,289 deaths among all categories of health care professionals, including 169 nurses.

The loss of so many dedicated, deeply experienced professionals in such an urgent crisis is “unfathomable,” said Christopher Friese, a professor at the University of Michigan School of Nursing whose areas of study include health care worker injuries and illnesses. “Every worker we’ve lost this year is one less person we have to take care of our loved ones. In addition to the tragic loss of that individual, we’ve depleted our workforce unnecessarily when we had tools at our disposal” to prevent wide-scale sickness and death.

One of the most potentially powerful tools for battling COVID-19 in the medical workforce has been largely missing, he said: reliable data about infections and deaths. “We don’t really have a good understanding of where health care workers are at greatest risk,” Friese said. “We’ve had to piece it together. And the fact that we’re piecing it together in 2020 is pretty disturbing.”

The CDC and the Department of Health and Human Services did not respond to ProPublica’s questions for this story.

Learning from the sick and dead ought to be a national priority, both to protect the workforce and to improve care in the pandemic and beyond, said Patricia Davidson, dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing. “It’s critically important,” she said. “It should be done in real time.”

But data collection and transparency have been among the most glaring weaknesses of the U.S. pandemic response, from blind spots in the public health system’s understanding of COVID-19 in pregnancy to the sudden removal of hospital capacity data from the CDC’s website, later restored after a public outcry. The Trump administration’s sudden announcement in mid-July that it was wresting control over hospitalcoronavirus data from the CDC has only intensified the concerns.

“We’d be the first to agree that the CDC has been deficient” in its data gathering and deployment, said Jean Ross, a president of National Nurses United. “But it’s still the most appropriate federal agency to do this, based on clear subject-matter expertise in infectious diseases response.”

The CDC’s basic mechanism for collecting information about health care worker infections has been the standard two-page coronavirus case report form, mostly filled out by local health departments. The form doesn’t request much detail; for example, it doesn’t ask for employers’ names. Information is coming in delayed or incomplete; the agency doesn’t know the occupational status of almost 80% of people infected.

The data about infections and deaths among nursing home staff is more robust, thanks to a rule that went into effect in April that requires facilities to report directly to the CDC. The agency told Kaiser Health News that it is also “conducting a 14-state hospital study and tapping into other infection surveillance methods” to monitor health care worker deaths.

Another federal agency, the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, investigates worker infections and deaths on a complaint basis and has prioritized COVID-related cases about the health care industry. But it has suggested that most employers are unlikely to face any penalties and has issued only four citations related to the outbreak, to a Georgia nursing home that delayed reporting the hospitalization of six staffers and three Ohio care centers that violated respiratory protection standards. Of the more than 4,500 complaints OSHA has received about COVID-19-related working conditions in the medical industry, it has closed nearly 3,200, a ProPublica analysis found.

Data problems aren’t just a federal issue; many states have fallen short in collecting and reporting information about health care workers. Arizona, where cases have been surging, told ProPublica, “We do not currently report data by profession.” The same goes for New York state, though a report in early July hinted at just how devastating the numbers there might be: 37,500 nursing home employees, about a quarter of the state’s nursing home workforce, were infected with the coronavirus from March through early June. Other states, including Florida, Michigan and New Jersey, provide data about employees at long-term facilitiesbut not about health care workers more broadly. “We are not collecting data on health care worker infections and/or health care worker deaths from COVID-19,” a spokesperson for the Michigan Health Department said in an email.

This problem is global. Amnesty International, in a July report, pointed to widespread data gaps as part of a broader suppression of information and rights that has left workers in many countries “exposed, silenced [and] attacked.” In Britain, where more than 540 medical workers have died in the pandemic, the advocacy group Doctors’ Association UK has begun legal action to force a government inquiry into shortages of personal protection equipment in the National Health Service and “social care” facilities such as nursing homes. And in May, more than three months after the first known medical worker’s death, the International Council of Nurses called for governments across the world to start keeping accurate data on such cases, and for the records to be centrally held by the World Health Organization. The WHO estimates that about 10% of COVID-19 cases worldwide are among health workers. “We are closely following up (on) these cases through our global networks,” a spokesperson said.

“Governments’ failure to collect this information in a consistent way” has been “scandalous,” said the council’s CEO, Howard Catton, and “means we do not have the data that would add to the science that could improve infection control and prevention measures and save the lives of other healthcare workers. … If they continue to turn a blind eye, it sends a message that [those] lives didn’t count.”

So regular people, like Rezba, have stepped up with their makeshift databases.

Rezba, 40, initially wanted a career in public health. While finishing her master’s degree at Emory University in Atlanta and for a few months afterward, she worked as a lab tech at the CDC, analyzing nasal swabs to track cases of MRSA, the flesh-eating bacteria. But she decided she cared more about people than bugs, so she headed to Virginia Commonwealth University medical school in Richmond, graduating in 2009 with plans to specialize in the treatment of chronic pain.

During her residency at VCU, her first rotation was in the neonatal intensive care unit. “There was a little baby I helped take care of for three weeks. And the very last day of that rotation, his parents withdrew care. … He was the first little person I pronounced dead. I went and cried in the stairwell after that.” Her next rotation was in the burn unit, then the emergency department. “It seemed like death was just everywhere,” Rezba said. Witnessing it “is something very separate from the rest of your life experiences. People look different when they’re dying. It’s not like TV. They don’t look like they’re sleeping. CPR is pretty brutal. Codes are pretty brutal.”

She began keeping a list as a way to process the grief. “In residency, you record everything — your case logs, the procedures you do. It was just sort of second nature to record their names.” Whenever a patient died she would make another entry in her notebook, then “I would kind of perseverate” — ruminate — “over their names.” At the end of the year, she took the notebook to church. “I lit candles for them. I prayed. And then I let it go.”

A decade later, Rezba was working full time as an anesthesiologist and raising three small children, her list-compiling days long past her, she thought. Then COVID-19 hit. The onetime infectious disease geek became obsessed with the videos leaking out of China — the teams of health care workers in full protective gear, the makeshift wards in tents, the ERs in chaos: “I knew early on that this was going to be a big problem.” In her job, Rezba was often called upon to do intubations. “The possibility of not having enough PPE caused a lot of anxiety for her,” said her husband, Tejas Patel, whom she met in medical school. “She would be the one, if we did hit that level of New York, who could potentially be at risk and bring it home to the kids.”

As it turned out, Rezba’s hospital wasn’t inundated, nor did it experience the PPE shortages that plagued many health care facilities. But her anxiety didn’t disappear; it just took a new shape. If health care workers were front-line heroes, she decided, her role was to search the trenches for the bodies left behind.

Rezba is the first to admit she’s not great at technology; she rarely uses a computer at home. Patel discovered what she was doing because their iPhones and iCloud accounts are linked. “Whenever she saves a picture to the phone, I can see it. And I noticed a bunch of pictures of, you know, these strangers.” He remembered how, in their student days, Rezba had insisted on humanizing the cadaver in their anatomy lab: “It upset her that it was just this anonymous person. Knowing his birthday and little things like that would make her feel better.” Patel figured the photos were part of a similar coping strategy. “It wasn’t until much later that I found out she was putting them up on Twitter.”

Much of Rezba’s digging happens in the middle of the night, when she can’t sleep. She usually starts by Googling for local news stories; if she’s still not tired, she turns to the obituary site Legacy.com. The hunt for a person’s occupation and cause of death invariably takes her to Facebook, where she follows the trail to relatives and co-workers, to vacation slideshows and videos of old men serenading their grandkids on the guitar. Every few days, she checks GoFundMe, where she’s recently been struck by the number of people who linger for weeks or months before dying. She’s still discovering deaths that occurred in April and May. Anyone under 60 gets special scrutiny. “If the obit says, ‘They died surrounded by family,’ I usually don’t bother trying to find out more, because those people didn’t have COVID. The people with COVID are mostly dying alone.”

Doctors and nurses are the easiest to find. “If someone worked in the laundry service at the nursing home, the family doesn’t put that in,” Rebza said. Yet it’s the nonmedical staff that she feels a special obligation to uncover — the intake coordinators and supply techs, the food service workers and janitors. “I mean, the hospital’s not going to function if there’s nobody to take out the trash.” Every so often, a news story mentions that several staffers from a particular nursing home or rehab center have died, without mentioning their names, and Rezba feels the rage start to bubble. “What it comes down to is, these are people that are making $12 an hour. And they get treated like they’re disposable.”

If she can’t find someone’s identity right away, or if the cause of death isn’t clear, she’ll wait a couple of days or weeks and try again. Because she comes across them anyway, she’s started to keep track of other categories of COVID-19 deaths, like kids and pregnant women, as well as health care workers in their 30s and 40s who don’t appear to have the virus but suddenly perish from heart attacks or strokes or other mysterious reasons. “I have a lot of those,” she said.

Once she’s certain she’s found someone who belongs on her list, she selects a photo or two and writes a few words in their honor. Sometimes, these read like a scrap of poetry; sometimes, like a howl.

He enjoyed crazy-dancing at home to Bruno Mars, with the moves becoming wilder the more his family laughed.

As a child, she would wrap her clothes around Dove soap so they would smell like America.

This poor baby should have his mother in his arms. Instead he has her in an urn.

A preprint study out of Italy last week hinted at the kind of lessons researchers and policy makers might glean if they had more complete data about health care workers in the U.S. The study pooled data from occupational medical centers in six Italian cities, where more than 10,000 doctors, nurses and other providers were tested for coronavirus from March to early May. Along with basic demographic information, the data included job title, the facility and department where the employee worked, the type of PPE used and self-reported COVID-19 symptoms.

The most important findings: Working in a designated COVID-19 ward didn’t put workers at greater risk of infection, while wearing a mask “appeared to be the single most effective approach” to keeping them safe.

In the U.S., many medical facilities are similarly monitoring employee infections and deaths and adjusting policies accordingly. But for the most part, that information isn’t being made public, which makes it impossible to see the bigger picture, or for systems to learn from each other’s experiences, to better protect their workers.

Imagine all of the opportunities it would present if everyone could see the full landscape, said Ivan Oransky, vice president for editorial content at Medscape, where a memorial page to honor global front liners has been one of the site’s best-read features. “You could be doing some real great shoe-leather epidemiology. … You could go: ‘Wait a second. That hospital has 12 fatalities among health care workers. The hospital across town has none. That can’t be pure coincidence. What did this one, frankly, do wrong, and what’s the other one doing right?’”

To Adia Harvey Wingfield, a sociologist at Washington University and author of “Flatlining: Race, Work, and Health Care in the New Economy,” some of the most pressing questions relate to disparities: “Where is this virus hitting our health care workers hardest?” Is the impact falling disproportionately on certain categories of workers — for example, doctors vs. registered nurses vs. nursing aides — on certain types of facilities, or in certain parts of the country? Are providers who serve lower-income communities of color more likely to become ill?

“If we aren’t attuned to these issues, that puts everybody at a disadvantage,” Wingfield said. “It’s hard to identify problems or identify solutions without the data.” The answers are especially important in Black and Latino communities that have suffered the highest rates of sickness and death — and where health care workers are themselves more likely to be people of color. Without good information to guide current and future policy, she said, “we could potentially be facing long-term catastrophic gaps in care and coverage.”

The near-term consequences have also been enormous. The lack of public data about health care workers and deaths may have contributed to a dangerous complacency as infections have surged in the South and West, Friese said — for example, the idea that COVID-19 is no more dangerous than other common respiratory viruses. “I’ve been at this for 23 years. I’ve never seen so many health care workers stricken in my career. This whole idea that it’s just like the flu probably set us back quite a way.”

He sees similar misconceptions about PPE: “If we had a better understanding of the number of health care workers infected, it might help our policymakers recognize the PPE remains inadequate and they need to redouble their efforts. … People are still MacGyvering and wrapping themselves in trash bags. If we’re reusing N95 respirators, we haven’t solved the problem. And until we solve that, we’re going to continue to see the really tragic results that we’re seeing.”

The misconceptions appeared to stretch to the highest reaches of the federal government, even as infections and deaths started surging again. At a White House event in July focused on reopening schools in the fall, HHS secretary Alex Azar told the people gathered, “health care workers … don’t get infected because they take appropriate precautions.”

Even some medical workers have continued to be in denial. A few days before Azar spoke, Twitter was abuzz over an Alabama nurse who worked the COVID-19 floor at a hospital by day and decompressed at crowded bars by night, where she often went maskless. “I work in the health care industry,” she was quoted as saying, “so I feel like I probably won’t get it if I haven’t gotten it by now.”

Piercing that sense of invulnerability — making the enormity of the COVID-19 disaster seem real — isn’t only Rezba’s mission. From The New York Times’ iconic front page marking the first 100,000 American deaths to the Guardian/Kaiser Health News project “Lost on the Frontline,” news organizations and social media activists have grappled with how to convey the scale of the tragedy when people are distracted by multiple world-shattering crises and the normal rituals for processing grief are largely unavailable.

“The point at which accountability usually happens is when our leaders have to reckon with the families of those who’ve been lost, and that has not happened,” said Alex Goldstein, a Boston-area communications strategist behind the wrenching @FacesOfCOVID Twitter account, which has posted almost 2,000 memorials since March. With COVID-19, “no one has had to look in the eye of a crying parent who wants to show you a picture of their child or listen to someone telling you about who their mom or dad was. There has been no consequence. What would our policy decisions have looked like if [the people making them] had to come face to face with that death and loss in a more visceral way?”

It’s a question that weighs especially heavily on health care professionals, who have seen, in the most visceral way possible, the worst that COVID-19 can do. Erica Bial, a pain specialist in the neurosurgery department at a Boston-area hospital, fell dangerously ill from COVID-19 in March, her respiratory symptoms lingering for more than six weeks. She lived alone and opted not to go to the hospital, in part because she worried about infecting other people. “At that point [in the outbreak], they would have intubated me, given me hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin and probably killed me.” As her recovery dragged on, she wondered how other doctors were faring: “I couldn’t believe that I was the only physician I knew who was sick.” But as she searched online, “I could not find any data. I just started getting really frustrated at the lack of information and the disinformation. … And then I started thinking about, well, what happens if I die here? Will anybody know?”

Like Rezba, Bial has a background in public health; the Facebook page she created, COVID-19 Physicians Memorial, was an attempt to build “a network where there’s accountability. I wasn’t necessarily trying to create, you know, reverence or memorialization. I was trying to understand the scope of the problem.”

Rezba soon began posting memorials on the page; as it grew to include more than 4,800 members, Bial asked her to help moderate it. Among the things the two women share is a determination to stick to facts. “I didn’t want any politics and I didn’t want any garbage,” Bial said. “(Rezba) was 100% like-minded and trustable.” She was also someone Bial could talk to, doctor to doctor, as she recovered. “It wasn’t just two people obsessed with something kind of morbid,” Bial said. “She was a source of support.”

Emergency room doctor Cleavon Gilman also gained a following for his posts on Facebook, a diary about what he witnessed as an ER resident in the NewYork-Presbyterian hospital system, battling the virus as it engulfed Washington Heights. “It was just … overwhelming,” he recalled. “We were intubating 20 patients a day. We had hallways filled with COVID patients; there was nowhere to put them.” In the space of a few brutal days in late April, three of Gilman’s colleagues died, including one by suicide. “When it’s a colleague that you’re taking care of and you know them as a person you’ve been on a journey with … man, that’s hard.”

Though much of the media focus was on the risks faced by older patients, Gilman was struck by how many of the critically ill were in their 20s, 30s and 40s. In mid-April, his own 27-year-old cousin, a gym teacher at a New Jersey charter school, suddenly died; he went to the ER twice with chest pain but was diagnosed with anxiety and sent home, according to his relatives, only to collapse in his car on the side of the road.

As the crisis in New York City ebbed, Gilman could see trouble ahead in other parts of the country, including in Yuma, Arizona, where he was about to start a new job. It seemed vitally important to help younger people understand the risks they faced — and that they created for others — by not adhering to physical distancing or wearing masks, not to mention the dangers that health care workers faced from continuing shortages of PPE. So Gilman began gathering the memorials he saw on Twitter and Facebook, many of them found by Rezba or on @FacesOfCOVID, and organizing the dead on his website in the type of gallery that he knew would pack an emotional wallop. Then he went a step further, making the photos and obituaries — more than 1,000 people — sortable by age and profession.

“You begin to see a pattern here,” he said. “When someone says, ‘Oh people aren’t dying, they’re not that [young],’ you can come back with actual names, actual articles, quickly. It’s more powerful. You have your evidence there.”

One of the most overtly political projects is Marked by COVID, formed by Kristin Urquiza in honor of her father, Mark, after her “honest obituary” of him went viral in early July. To Urquiza, who earned her master’s in public affairs from the University of California, Berkeley, and works as an environmental advocate in the San Francisco area, “the parallels between the AIDS crisis and what is happening now with COVID are just mind-boggling [in terms of] the inaction by governments and the failure to prioritize public health.” She and her partner, Christine Keeves, a longtime LGBTQ activist, hope the project will be both “a platform for people to come forward and share their stories” and the COVID-19 version of the anti-AIDS group Act Up.

They’re also raising money on GoFundMe to help other families pay for obituaries; the second honest obit on their site was for a respiratory therapist in Texas named Isabelle Odette Hilton Papadimitriou: “Her undeserving death is due to the carelessness of politicians who undervalue healthcare workers through lack of leadership, refusal to acknowledge the severity of this crisis and unwillingness to give clear and decisive direction to minimize the risks of coronavirus. Isabelle’s death was preventable; her children are channeling their grief and anger into ensuring fewer families endure this nightmare.”

It’s a trend that Rezba supports wholeheartedly. By the end of July, she had posted almost 900 names and faces of U.S. health care workers who had perished from COVID-19. She fantasized about what it would be like to leave the counting behind her. “It would be great if I could stop. It would be great if there was nobody else to find.” But she had a backlog of dozens of stories to post, and the number of deaths kept climbing.

Ryann Grochowski Jones and Hannah Fresques contributed reporting.