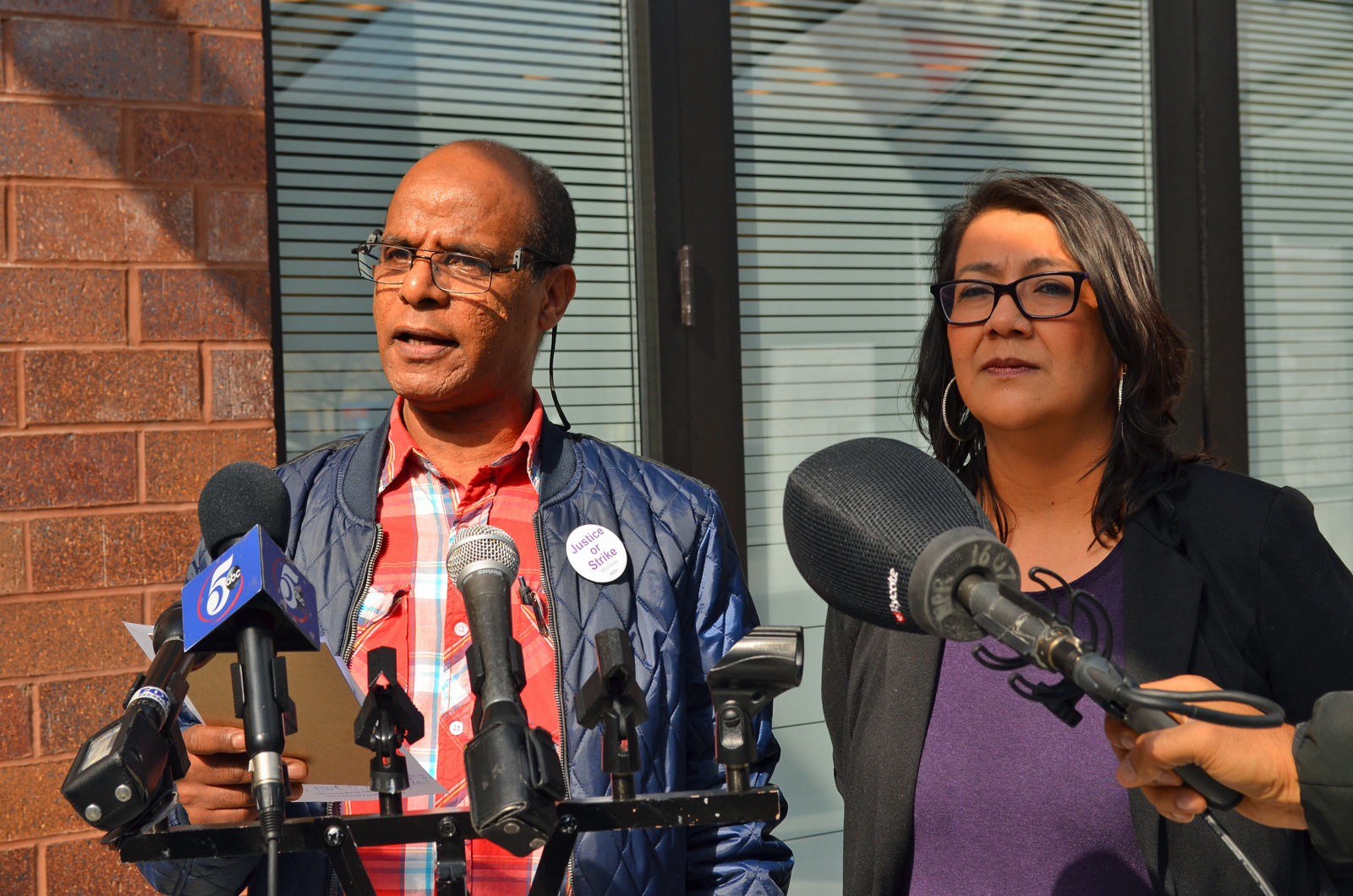

Ahmed Kahsay, a janitor at MSP Airport, speaks at a press conference called by his union, SEIU Local 26, to discuss the coronavirus, as Local 26 President Iris Altamirano (R) listens.

Share

The coronavirus outbreak has Edith Patiño worried not just about her family’s health, but her ability to pay the bills, too.

After eight years working as a janitor for Minneapolis-based Harvard Maintenance, Patiño gets just four days of earned sick and safe time per year. When she runs out, Patiño said, she often goes to work sick rather than lose hours toward her paycheck.

What would it mean to miss work for two weeks while recovering from COVID-19?

“I am the head of my household,” Patiño said. “It would be detrimental. I would have to ask for government assistance, which I don’t want to do and have never had to do. But if I can’t work, I have no other option.”

Public response to the epidemic has put a grim spotlight on limited access to paid sick time in the U.S., particularly for low-wage workers like Patiño.

According to federal labor-market statistics, 73% of all private-sector workers had access to paid sick leave last year, but less than half of workers in the lowest 25% of earners. Access to paid sick time also was lower among workers in service occupations, who are most likely to interact with the public, making containment of the outbreak more challenging.

As news broke today that two passengers arriving at Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport had been asked to self-quarantine, the union representing 4,000 Twin Cities janitors, including about 200 who clean the airport, carried a new sense of urgency into contract negotiations with local cleaning contractors.

Among janitors’ top demands is an increase in their earned sick and safe days, to a minimum of six per year.

Iris Altamirano, president of Service Employees International Union Local 26, said union members “will be on the front lines” of preventing the virus from spreading in Minnesota. “Our workers are being given new tasks to do right now, like wiping down chairs, doorknobs and other surfaces,” Altamirano said.

Should they fall ill from the virus, janitors want their union contract to provide basic protections for themselves and their communities, like paid sick time and affordable health insurance. Altamirano said the union hopes to use its leverage at the bargaining table “to tackle something bigger than just us.”

“We know right now we’re under threat, and we are part of the solution to containing that virus,” Patiño added.

If negotiators fail to make meaningful progress on those demands and others in contract talks scheduled through Friday, the union’s 4,000 members, who staged a 24-hour strike last week, plan to begin an open-ended strike over unfair labor practices Monday.

“We are coming into these negotiations very hopeful we can land a settlement but preparing to do whatever we have to do to get a fair contract,” Altamirano said.

Local 26 members in negotiations are employed by over a dozen different subcontractors to clean corporate office buildings across the Twin Cities. They voted unanimously Feb. 8 to authorize a ULP strike over the companies’ practices of stalling and refusing to give information, and to settle a fair contract.