Share

March 5, 2015, is an important anniversary for the Minneapolis Labor Review newspaper, founded in 1907.

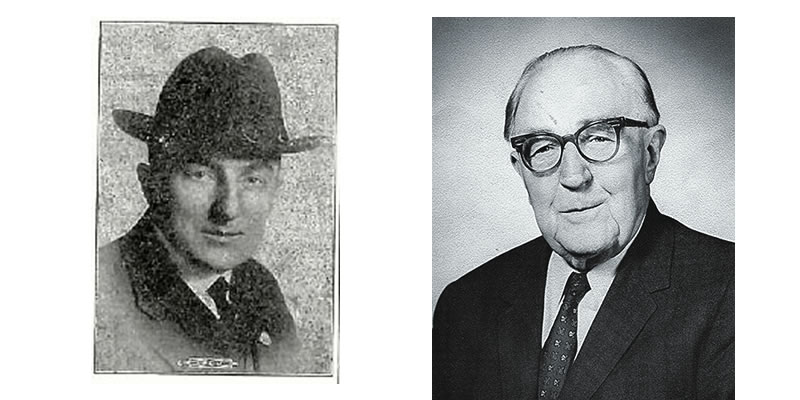

Published 100 years ago, the March 5, 1915, issue of the Labor Review was the first issue bearing the name of “R.D. Cramer” as the newspaper’s editor. Robley D. Cramer, 31 years old at the time, would continue as Labor Review editor for 48 years until he retired in 1963. He remains the longest-serving editor of the Labor Review in its now nearly 115-year history.

Cramer was not just the editor of the Labor Review. He became one of the local labor movement’s most eloquent speakers. He served as a top strategist advising union leaders during the pivotal Teamsters strike in 1934 and the Strutwear strikes in 1935-1936.

Farmer-Labor Party Governor Floyd B. Olson hailed Cramer — his friend and advisor — as “Mr. Minneapolis Labor.”

And when Cramer died in 1966, newspaper obituaries referred to him as the “godfather” of the local labor movement.

The Minnesota Historical Society is the repository for six boxes of Cramer’s papers, including speeches, letters, and scrapbooks of newspaper clippings. Cramer’s correspondents, among many leading figures of the times, included Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene Debs, Governor Floyd B. Olson, and Wilbur Foshay, builder of the landmark Foshay Tower in Minneapolis.

A letter from Debs to Cramer begins, “Dear Comrade Cramer.” A letter from Governor Olson to Cramer commends Cramer for a speech broadcast on the radio. In letters and in the pages of the Labor Review, Cramer celebrated Foshay for using all-union construction labor for the tower, completed in 1929.

‘Defending the underdog’

Born in New York state in 1884, Cramer earned a law degree but headed west for the rough and tumble Nevada gold fields. “Instead of finding gold, he found himself defending the underdog in many a court case,” one account of Cramer’s life related. On the way back east, Cramer stopped in Minneapolis to visit an uncle and never left.

Cramer joined the Upholsterer’s Union in 1913 and also became involved with the Labor Review, helping to sell ads at first, then writing editorials, then winning election as editor of the newspaper in 1915 during a period of restructuring of the newspaper.

Only the initials “R.D.C” signed to an editorial Sept. 4, 1914, appear to mark the beginning of Cramer’s many years writing for the Labor Review.

In Cramer’s first issue as editor, March 5, 1915, he titled his editorial “Workers All” and wrote: “Most of the discord in the Labor Movement comes when men forget that no matter what their brothers’ politics or religions are they are all workers. It will be the policy and effort of “Labor Review” in the year to come to make its readers think, and work and live as workers. To make them realize that their salvation lies in recognizing that first, last and all the time they are workers, and that religious and political differences are stirred up among us to keep us divided, that we may be more easily conquered.”

In July 1920, the Labor Review became the center of a legal drama when editor Cramer refused to abide by a court injunction to stop running calls for a boycott of the Wonderland Theatre, which had fired its union movie projectionists and replaced them with cheaper workers.

Ordered to pay fines or go to jail, Cramer and three officers of the Minneapolis Trades and Labor Assembly chose jail. Cramer and the three union officers went to the courthouse Aug. 28, 1920, to turn themselves in — with 20,000 union members parading with them, accompanied by a marching union band.

Cramer and the others spent 63 days in the jailhouse. Cramer continued to edit the Labor Review from the jail, however, and the newspaper continued to urge readers not to patronize the Wonderland Theatre. His efforts were a direct challenge to the powerful Citizen’s Alliance, a business group that was determined to drive unions from Minneapolis. The Alliance eventually crumbled as workers of all kinds began organizing.

Witnessing the movement’s growth

Cramer continued to serve as Labor Review editor through the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, the decades which saw the U.S. labor movement grow to the peak of its power and influence. Many industries in Minneapolis, from flour milling and trucking to grocery stores and manufacturing plants, were unionized.

In 1961, national AFL-CIO President George Meaney appointed a trustee to take charge of the Minneapolis Central Labor Union Council, “following the receipt of certain allegations concerning financial mismanagement and violations.”

A significant part of the debt: the unpaid Labor Review tab at the printer. The debt had grown because the newspaper had been balancing its books with accounts receivable that were proving uncollectable.

When the CLUC emerged from trusteeship a year later, the new CLUC charter provided for the CLUC president to appoint the Labor Review editor (under the old charter, the editor was elected — Cramer had run and won since 1915 with no one daring opposition).

Under the terms of a negotiated retirement, Cramer would continue to write a weekly column for the newspaper for a $100 per week stipend as “editor emeritus.” His column, however, would be subject to the new editor’s review. The last Labor Review issue listing Cramer as editor was dated Dec. 27, 1962.

Cramer was honored at a retirement dinner Jan. 30, 1963, at the Leamington Hotel. A crowd of 600 people attended. Minneapolis Mayor Arthur Naftalin presented Cramer with the city’s Distinguished Service Award.

Cramer continued to write his weekly column, focusing on imparting lessons of labor history, until he died July 31, 1966, at age 82. He is buried in Lakewood Cemetery.

Cramer’s death made front page news in the Minneapolis Tribune, the newspaper he so often criticized. “He was cited both by friends and enemies — and there were many of each — as the godfather of the Minneapolis labor movement,” the news story read.

Cramer died of a heart attack just hours after he wrote a final Labor Review column. In it, he concluded: “There is no brighter spot in union labor history than the trade union movement of the state of Minnesota. It is a splendid rank and file movement. Let us all work to continue its success.”

Note: This story includes reporting from a 2007 series of stories marking the 100th anniversary of the Minneapolis Labor Review. View more from the series at the Minneapolis Regional Labor Federation website.