Share

It’s a dull but important area of the law – and one that affects workers every day, from union elections to rules governing when sleepy truckers must pull off the road.

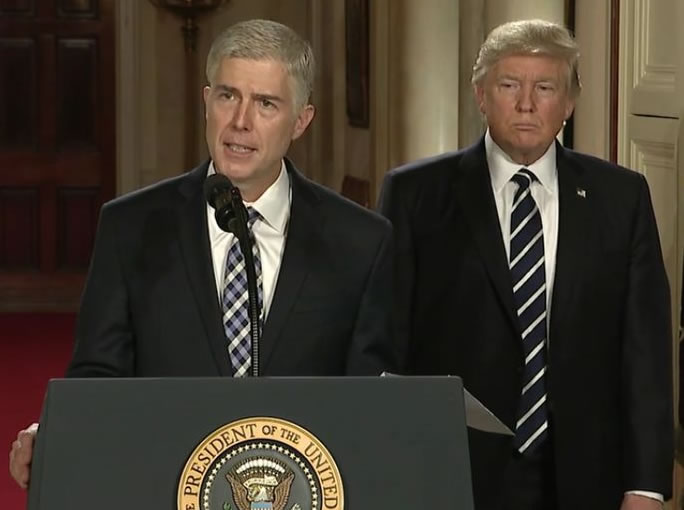

If Neil Gorsuch, President Trump’s nominee for the U.S. Supreme Court, wins that seat and gets his way, he could use it to upset a lot of workers’ applecarts.

The field is called administrative law, and Gorsuch wants to turn the final say on it upside down, putting a lot more of the ultimate outcomes, if not all of them, in judges’ hands.

Administrative law is a fancy name for law covering agency rulings – everything everything National Labor Relations Board decisions on who can vote in union recognition elections to Labor Department rules against wage theft to Transportation Department standards on how many consecutive hours a trucker may spend behind the wheel before taking a rest break.

Right now, when the NLRB makes a decision on whether to uphold or throw out a union recognition vote, for example, the loser – the company or the union – can and often does take it to court. That’s when administrative law kicks in.

Once they get there, a 33-year-old U.S. Supreme Court ruling involving Chevron Oil Company tells judges that while they may take the case, they generally must defer to the agency’s expertise and decisions.

That principle – that the agency generally is correct — is called Chevron deference. Chevron lets agencies fill in gaps that Congress leaves in laws.

And it says judges are supposed to overturn Chevron deference only when (a) the agency can’t provide well-proven reasons for what it did, or (b) when the agency didn’t give the public the chance to comment, support or protest a proposed agency rule, or (c) both.

Not if Neil Gorsuch has his way. He wants to leave everything in the hands of the judges, and let them start from scratch, disregarding an agency’s findings, its expertise and all the comments it got, if necessary.

That’s the interpretation of Gorsuch’s stand by Matthew Wessler, a pro-worker lawyer who specializes in that field, class action lawsuits and fighting for workers in arbitration cases.

Wessler and two experts in other areas – the American Civil Liberties Union’s deputy legal director Louise Welling and former Obama White House deputy counsel Christopher Kang – analyzed Gorsuch’s record at a Feb. 23 forum of the American Constitution Society, an organization of progressive attorneys, including pro-worker attorneys.

Right now, if the NLRB can show in court that it meets Chevron standards when it decides a labor case, or if OSHA satisfies both Chevron conditions when it defends its beryllium regulation, for example, judges are supposed to back the agency.

Gorsuch, now a federal appellate judge in Denver, doesn’t like that, Wessler says.

“He said, to be blunt, that Chevron was a bad idea and should be overruled. He’d breathe more life into having courts review agency decisions,” Wessler said. Even the late Justice Antonin Scalia didn’t go that far, but Chief Justice John Roberts also challenges Chevron deference, Wessler noted.

In practical terms, Wessler said that if Gorsuch wins the High Court seat and convinces four of his colleagues to bounce Chevron deference, “an NLRB decision that attempts to step in and protect workers would only be enforceable consistent with what Congress intended.”

In a long and detailed dissent on an immigration case in 2016, Gorsuch “laid out a distinct theory about separation of powers” that gives judges more power to completely disregard an agency’s expertise in the field, Wessler explained.

“Not only have agencies arrogated more power than the Founders or (prior) cases allowed, “ but Gorsuch also says agencies “took power away from Congress, by expanding Chevron, and requiring almost complete deference to agency policies,” Wessler explained.

In the last big ruling involving Chevron deference, pitting the city of Arlington, Texas against the Federal Communications Commission in 2013, the justices ruled for the FCC, 6-3. Scalia – whose seat Gorsuch would take – wrote the majority ruling and Justices Samuel Alito and Anthony Kennedy joined Roberts in dissent. “A court should not defer to an agency until the court decides, on its own, that the agency is entitled to deference,” Roberts wrote.

Gorsuch’s views on agency rules seem to be in line with Trump’s. The president has already issued an executive order telling agencies they must dump two rules for every one they issue. The Communications Workers are challenging it in federal court in D.C.

Trump’s senior strategist and advisor, extreme nationalist Stephen Bannon, told a conference of right wingers in the D.C. suburbs on Feb. 22 that his boss agrees with “deconstruction of the administrative state.” That’s “the reason” for Trump’s Cabinet picks, Bannon said. “The way the progressive left runs, if they can’t get it” – an idea – “passed (in Congress), they’re just going to put in some sort of regulation in an agency.”

The Senate Judiciary Committee has scheduled hearings on Trump’s nomination of Gorsuch for March 20-23.