Share

This story was originally published by ProPublica. ProPublica Illinois is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to get weekly updates about our work.

This week, Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul announced the settlement of a sexual harassment and job retaliation case involving female temporary workers at a southwest suburban beauty supplies factory. The settlement, which includes implementation of a two-year independent monitor to protect workers from further harassment and retaliation, is a victory for vulnerable Latina immigrant workers who rarely speak out against this type of abuse.

We never reported on the allegations at Voyant Beauty, previously known as Vee Pak LLC, in Countryside. So, you may be wondering, why am I telling you about this now? Well, sometimes you come across a story you want to write about but, for one reason or another, you don’t. You “gather string,” as we say, and hope the right moment comes. Monday’s announcement of the settlement felt like the right moment to revisit this issue.

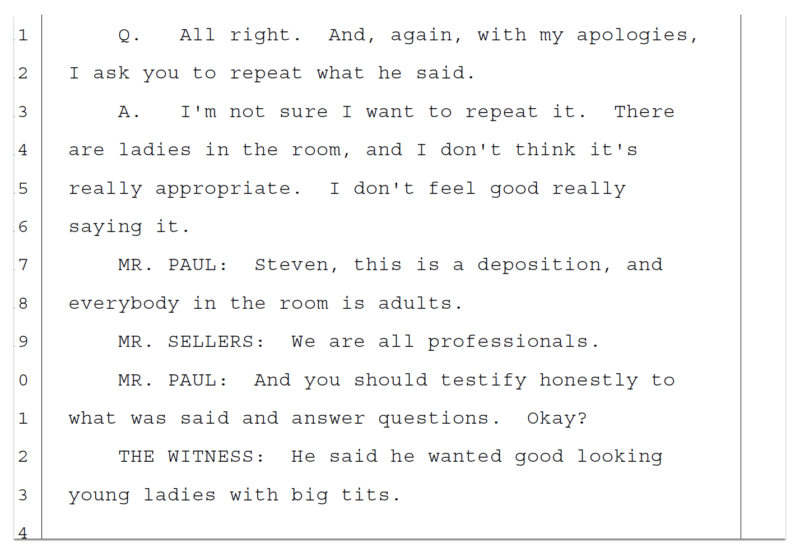

I first heard of problems at Vee Pak almost two years ago. A source had tipped me off to the sworn deposition of a temporary staffing agency executive in a separate case who was asked to describe what kind of workers a Vee Pak supervisor would request.

His response was explosive: “He wanted good looking young ladies with big tits.”

The deposition was part of an ongoing lawsuit against Vee Pak and the temp agencies it contracted with that focused on allegations of discrimination against prospective African American workers. (Vee Pak has denied the allegations. Ownership of the company has changed since the discrimination case was filed in 2012, and it was renamed Voyant Beauty last year. A Voyant official said the company has “nothing to do” with the earlier lawsuit, which was “carved out of the deal.”) While the lawsuit dealt with alleged racial discrimination, the deposition indicated that another form of abuse could be happening at the factory.

At the time, we were in the middle of a national moment of reckoning, as women in Hollywood and around the country spoke out about sexual harassment in the workplace in what became the #MeToo movement. I started hearing about rampant sexual harassment, coercion and abuse of undocumented immigrant women in low-wage, temporary factory jobs. I wanted to write about this but couldn’t get to it immediately because I was so busy with other stories.

Then last summer, I learned that female temp workers at Voyant were organizing to speak out against sexual harassment. I soon met more than a dozen women who said that male mechanics would grope them, leer at their breasts and make sexual comments or physical insinuations about sex. They said the harassment had been going on for years and that the #MeToo movement had given them the courage to speak out. With the help of the Chicago Workers’ Collaborative, a nonprofit organization that focuses on temp workers, the women got about 50 co-workers to sign a petition demanding an end to the sexual harassment, writing that they had “endured Voyant Beauty employees touching us in our private parts, making obscene comments and gestures, and creating a hostile work environment which is toxic and extraordinarily traumatic.” They held demonstrations outside the factory and at the company’s offices a few miles away.

Isaura Martinez, a former temp worker who is now an organizer with the Chicago Workers’ Collaborative, said she’d never seen this level of collective action among temp workers fighting sexual harassment in the decade or so she’s been working in the industry.

“It was stunning to witness such a large group of workers get together and maintain their outrage and courage,” she said. “Sexual harassment is so common in the temp industry … and the workers feel powerless. They are easily intimidated and remain silent for fear of retaliation, fear of losing their jobs, fear that nobody will listen or believe them.”

In a statement, Voyant’s senior vice president of human resources, Ann Miller, said the company “has never tolerated workplace harassment, discrimination, or retaliation of any kind.” She said Voyant denies any liability or wrongdoing but entered into the consent decree to avoid the unnecessary expense of further litigation and business disruption. “This resolution enables greater focus on optimizing workplace inclusion, diversity, and employee complaint handling practices,” she added. “Our current zero-tolerance policies already meet or exceed any of the terms we are stipulating to.”

After the protests, which were mostly covered by Spanish-language media, some of the women said the staffing agency they worked for, Alternative Staffing Inc., stopped calling them back to work or reduced their hours. Several would eventually file complaints about job retaliation and sexual harassment with various federal and state agencies. Facing multiple investigations, the company eventually allowed workers to return, according to the attorney general’s office.

Alternative Staffing, which was mentioned in the attorney general’s lawsuit but was not a party to it, did not respond to a request for comment. The staffing agency stopped providing workers to Voyant in May, according to the attorney general’s office.

I wanted to understand the scope of the problem across the state, so I dug into the records and found there had been close to a dozen federal sexual harassment lawsuits filed on behalf of Illinois temp workers, usually working in factories or warehouses, over the previous decade. (Those cases represent the tip of the iceberg as others have been settled privately before the cases reach court.) They included allegations about supervisors and co-workers who grabbed women’s rear ends in freezers, pressed their genitalia against their bodies and demanded sex. Sometimes, when the women complained to management of harassment or failed to “play along,” they allegedly were fired or not asked to return to work. The cases also shared a common theme of the “host companies” claiming they had no liability since they were not the workers’ direct employers. Most ended in confidential settlements and only one, filed by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, ended with an agreement to make systemic changes at the workplace.

At the state level, then-Attorney General Lisa Madigan in 2018 sued a Bolingbrook warehouse operator and the temp agency it hired over both discrimination and sexual harassment over its treatment of female workers. That case, which ended in a consent decree last year, involved a mix of African American and Latina immigrant workers, said Roberto Clack, associate director of the nonprofit Warehouse Workers for Justice. “Our members feel like there’s a lot of discrimination in the workforce,” he said. “Part of it is gender, part of it is racial.”

I wanted to report on these issues but was also drawn to another, related reporting project on low-wage factory workers. So my editors and I agreed that I would monitor the sexual harassment issue but pursue the other project (which was delayed by the coronavirus pandemic but is ongoing). I kept in touch with the women at Voyant over the next several months and thought about them frequently.

When COVID-19 hit Chicago factories, I learned they were worried about getting sick on the job but felt they had no choice but to work. They had no other source of income and, as undocumented immigrants, didn’t qualify for unemployment or stimulus benefits. One of their co-workers eventually died.

All the while, Raoul’s office had been investigating an alleged pattern and practice of sexual harassment and job retaliation in violation of the Illinois Human Rights Act and had been in “comprehensive settlement negotiations” with Voyant. On Monday, the office filed both a lawsuit against the company over the allegations and the consent decree that resolves them.

“A workplace culture that subjects female employees to harassment and penalizes them for reporting such actions is reprehensible — and illegal,” Raoul said in a statement. “The workers at this facility had the courage to stand up against this terrible treatment. This consent decree will ensure Voyant’s unacceptable treatment of female employees will not stand any longer.”

The consent decree requires sexual harassment training for its employees and the appointment of an independent monitor to protect workers from further retaliation and sexual harassment. Voyant has agreed to pay $85,000 in penalties to cover the cost of monitoring.

Martinez told me the monitoring commitment is a huge victory for the workers, many of whom have since left Voyant but now “leave behind a legacy for their co-workers who remain.” What’s more, Martinez said she hopes the case can serve as an example to temporary workers elsewhere who may be afraid to speak out about sexual harassment.

That’s it from me. Please reach out with any questions, comments or story tips at melissa.sanchez@propublica.org. And stay safe.

P.S. Check out Will Evans’ reporting on discrimination against African-American temp workers for Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting, as well as my colleague Michael Grabell’s investigations into other exploitative conditions for temp workers in Chicago and across the country.