Share

If there are two constants in the history of the U.S. minimum wage, enacted in 1938 as part of the Fair Labor Standards Act, one is that it is critical to helping millions of workers rise out of poverty. The other is that many Republicans and businesses still oppose raising it.

At a Senate Labor Committee hearing earlier this year, in words that echoed the debates of 1938, U.S. Senator Lamar Alexander, R-Tenn., decried President Barack Obama’s proposal to raise the minimum wage to $9 an hour and index it to inflation. Currently, the wage falls far short of what a full-time worker needs to meet basic needs.

Raising the federal minimum wage, now $7.25, means employers would not be able to hire more low-wage workers, or might even have to let some go, Alexander said.

Advocates, including a businessman from St. Louis and Democratic senators, countered that studies show raising the minimum wage has little or no impact on hiring.

The St. Louis business owner, a record-video-CD-DVD distributor who pays his employees above the minimum wage, said raising it helps his business two ways. By putting a floor under workers’ wages, it reduces turnover. And by giving people more money to spend, they can use it to buy more goods, including his.

All this is reminiscent of the arguments over the minimum wage when lawmakers crafted the law in 1937-38. It went through the Senate 56-28, but only two of 15 voting Republicans backed it.

A “Dixiecrat” coalition of Republicans and Southern Democrats in the House rejected it twice before the AFL, the CIO and northern Democrats overcame their opposition in 1938. Even then, on the final 314-97 vote, the GOP barely backed establishing the minimum wage, 47-41.

Then, the Republicans hated the minimum wage hike because they were, as usual, listening to the Chamber of Commerce. And the Southerners hated it because they feared the law would force their slave-wage industries to actually pay workers something – especially if those workers were African-American.

This was despite the fact that the original Fair Labor Standards Act covered less than half of the U.S. workforce. Three big industries, agriculture, services and retail, were exempt. Agriculture still is, but the Kennedy administration pushed a law through Congress in 1961 bringing the other two in – over the strenuous opposition of those two sectors.

Outside sales personnel still aren’t covered by the minimum wage. Neither are supervisors. Neither are domestic servants. And, as the Service Employees International Union found when they sued several years ago on behalf of a worker in New York, neither are home health care workers hired by individuals and some agencies.

But there is still one other major hole in the minimum wage law that Congress has ignored: The tipped minimum wage. The Fair Labor Standards Act includes a separate minimum wage for workers who supposedly supplement their wages with tips: Restaurant servers, busboys and similar occupations.

And while the regular minimum wage was raised almost a decade ago, to $7.25 an hour, the tipped minimum hasn’t been raised in 22 years. It’s still $2.13 an hour, except in some states such as Minnesota and in the District of Columbia, which included tipped workers in their minimum wage increases.

Rep. Donna Edwards, D-Md., a former restaurant server, has introduced legislation to increase the federal minimum wage for tipped employees. In the GOP-run U.S. House, it’s going nowhere. Neither is Obama’s proposal. When Rep. George Miller, D-Calif., brought up a three-step minimum wage hike to $10.50 on the House floor earlier this year, the GOP shot it down on a party-line vote.

The tipped minimum would not be a problem if it worked like it’s supposed to, with workers earning, from tips, far and above the minimum wage. Except in too many cases, they don’t.

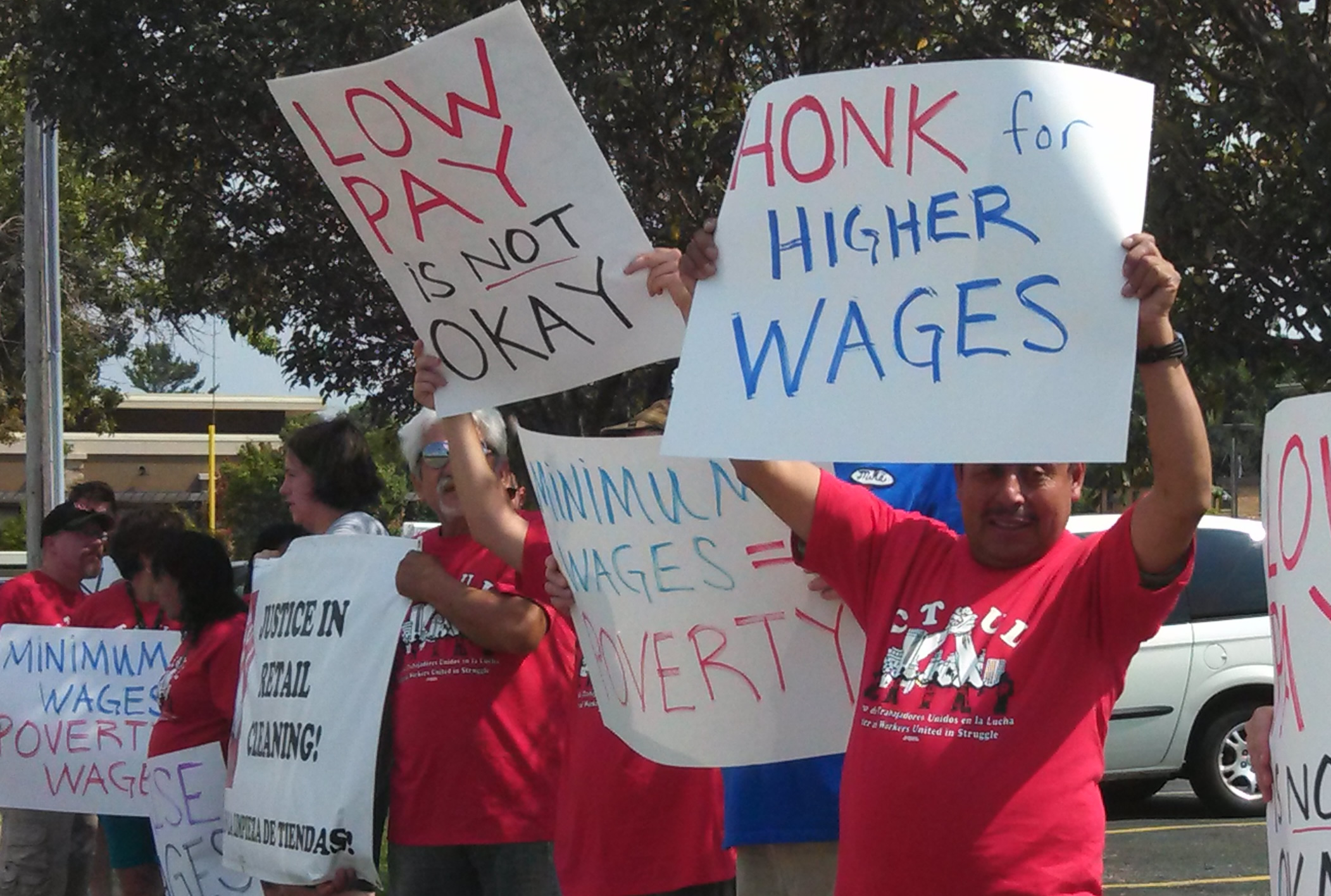

Workers testifying before the Senate Labor Committee and at rallies told of instances where they didn’t get paychecks at all – their wages were “under the table” in cash – or received a paycheck that said “zero.” And too often, managers in establishments where workers rely on tips skim a lot off the top.

The New York Court of Appeals recognized the plight of tipped workers in a class action suit that former baristas Jeana Barenboim and Jose Ortiz brought this year against their employer, Starbucks.

At Starbucks, baristas and shift supervisors, the first level up, share in the tips. The catch is the shift supervisors also have some management duties.

Starbucks sided with its shift supervisors, who argued they should share in the tips, too. The Court of Appeals, faced with a law the judges called “vague,” ruled for the supervisors. “An employee whose personal service to patrons is a principal or regular part of his or her duties may participate in an employer-mandated tip allocation arrangement, even if that employee possesses limited supervisory responsibilities,” the judges said.