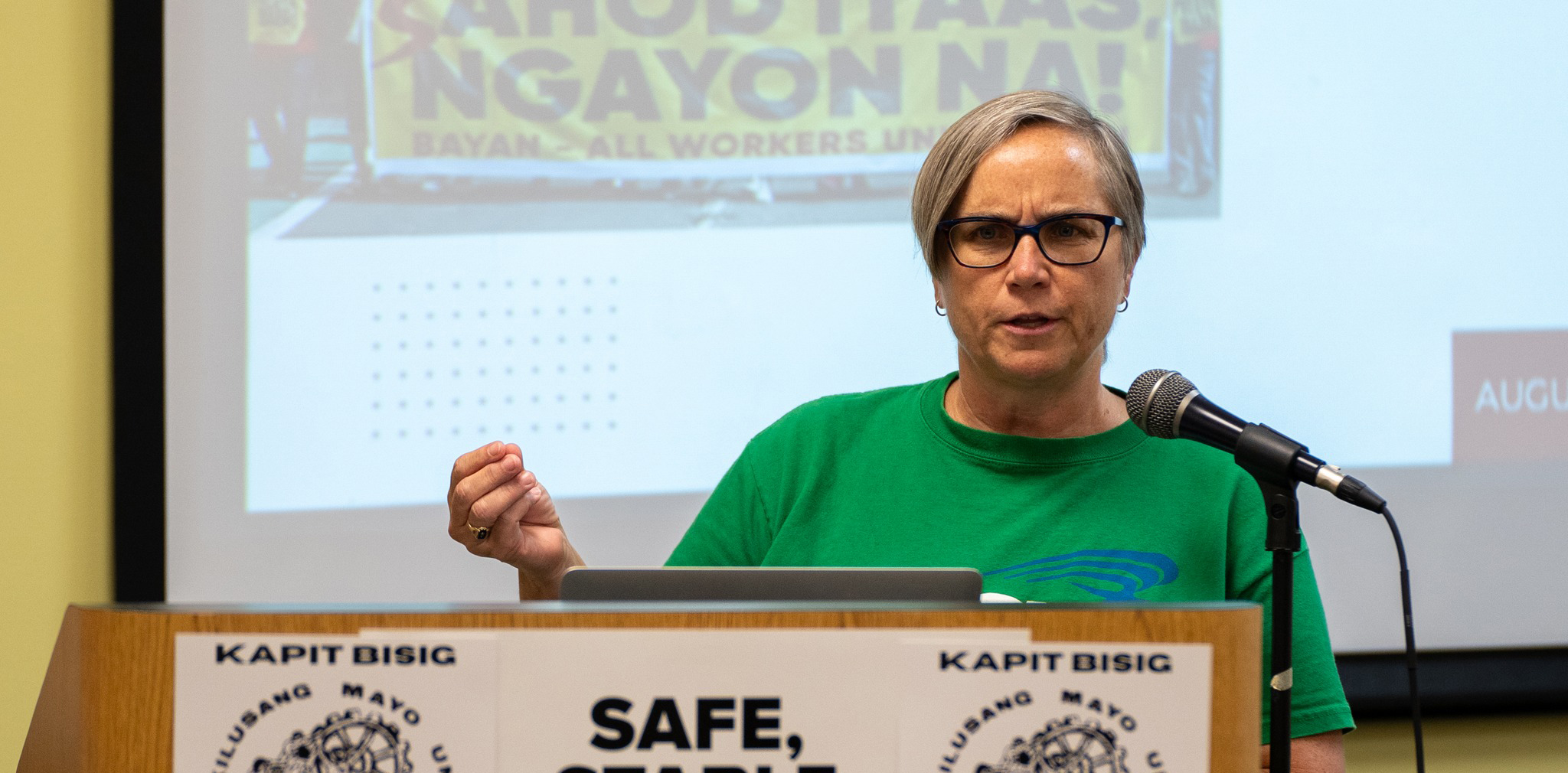

Cherrene Horazuk speaks at a solidarity event in Minneapolis with Philippines labor leader Elmer “Ka Bong” Labog. (Photo by Brad Sigal)

Share

“Cherrene has been my mentor and advocate for more than a decade,” says Max Vast in an email. Vast became president of AFSCME Local 3800 after longtime president Cherrene Horazuk resigned in October. “Her commitment to a member-led union has been particularly inspiring to me,” says Vast. “Even when it’s hard to get folks fired up, she is skilled at finding the issues that move people to action. She and I also share a deep passion for global solidarity. She spent many years doing solidarity work with El Salvador and I started my organizing in Palestine solidarity work. We both believe that solidarity with workers across the world is one of our most powerful tools.”

Horazuk’s journey in activism began as a student at the University of Minnesota in the 1980s while she was pursuing women’s studies and Latin American and African studies and history. She attended rallies calling for the end of university ties to South African apartheid. She saw how a multiyear campaign on campus led to divestment, and how a long struggle waged by communities working across borders won against an oppressive system.

She then became involved in the solidarity movement with Central America, specifically El Salvador, where U.S. influence was contributing to a brutal civil war. She moved to New York and eventually became the executive director of the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador where she organized opposition to U.S. military aid in the war and free trade policy, and coordinated humanitarian aid for people living in and fleeing from El Salvador, including support for the Salvadoran labor movement.

Horazuk is the granddaughter of rank-and-file Teamster Harry Horazuk, who participated in the 1934 truckers strike in Minneapolis. She was close with her father, James, a Teamster trucker who started his own business after his company closed as a union-busting tactic.

“When my mother had cancer when I was younger, she got incredible care because she had very good insurance that my dad’s union had fought for him that they’d won, and she lived years longer than she was supposed to,” says Horazuk. “When my dad was diagnosed, he died seven weeks later with a huge medical bill, and it really struck me. I saw the difference between having a job that’s unionized, and having a job that’s not.”

After her father died, Horazuk moved back to Minnesota just as clerical workers at University of Minnesota were on their first strike in the fall of 2003. Since then, she’s worked in the Humphrey School of Public Affairs dean’s office as an administrative specialist. Union organizing led her to being president of Local 3800 for more than a decade, and also led her to her partner, who she met while they were on strike together in 2007.

According to Horazuk, Local 3800 helped protect workers across the university during the COVID-19 pandemic by fighting for remote work and pay, and they also helped prevent the university from closing down UMN’s Child Development Center in 2018, which many students, staff, and faculty depended on for childcare. Horazuk spoke with Workday Magazine about her journey in and out of the labor movement and her next steps. The following interview has been edited for clarity.

Amie Stager: That must have been tough, losing your father so rapidly, coming back to Minnesota, realizing you needed to be here, and figuring out what you needed to do. How did you find out how to keep following your passion?

Cherrene Horazuk: “I saw the incredible resistance of the Salvadoran movement saying we want to determine our own destiny, and we don’t want to live under this level of repression. We would sleep overnight in union offices, because they were unlikely to be bombed or attacked if there were U.S. citizens there. In 1989, late October, the Salvadoran government bombed a trade union office. Over the lunch hour, there was a counter where union and community members would come in to eat, dozens of trade union leaders were killed in that bombing. There’s similarities to what’s going on right now in Gaza. Being able to say, ‘I saw communities that were bombed, and bombs that weren’t detonated that were made in the U.S.’ The labor movement there, that was very inspiring to me. The benefits and protections that people have is a really important part of why people look for specific jobs, or why people get stuck in crappy jobs. People work to take care of their families one way or another, however you define family.

I moved home to be closer to family and I wanted a job where I could continue my activism. This was at a time when very few unions were striking in the U.S. This group of primarily women stood up, and university administration didn’t think that they would do it, and they did. And I thought, “wow! This is where I want to get a job.”

Stager: It’s kind of like a given that we’re expected to take those benefits and protections for granted. Once you get those benefits, how do you make sure they’re not slowly stripped away from you?

Horazuk: Talking to people from other countries, they are astonished at some of the things that we think of as, “oh, this is the way it is!” And then you realize we’ve been taught to think that we are more developed than they are. In El Salvador, hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets to defend a national health care system. Panama has had extensive paid parental leave since the 40s. The U.S. has no paid parental leave.

Stager: Today, it feels like I’m always reading more and more about unions and workers going on strike. Thinking about the time we’re in and the shifting collective moods and attitudes toward striking, what has gotten workers from thinking, “are we even allowed to do this?” To, “do we as a group want to go on strike, and how?”

Horazuk: There’s a real gender dynamic. As a predominantly female workforce, we can be and most are primary breadwinners. Any discussion around living wages needs to be based on not what it takes to have a family with two incomes, but a single person, so that you can leave an abusive situation, you can raise your kids, take care of yourself, and not think, how do I pay rent? Do I stay here where I have housing? How do I get out of this unsafe situation?

As clerical workers at the university, there’s this perspective that we do the behind-the-scenes work, and we’re not going to stand up for ourselves. Members care about the work that they’re doing and don’t want to let the students or faculty down. We want to make sure that things are running and that can get used against us at times, our commitment to the institution. People would say, it’s the worst-case scenario if you end up on strike, and you shouldn’t do it. And it’s like, no, we need to take a stand and send a message that we’re gonna stand up and not be rolled over. We’ve seen this year with UPS workers and auto workers and SAG-AFTRA, right? It’s how you move forward.

Stager: A lot of the clerical positions are important to running the university. How did your job at the university inform your union activism and vice versa?

Horazuk: Being part of that policy milieu, I was interested in the Humphrey School. I appreciated being able to work in a place where the things that people were doing and the work that was happening was something that I could relate to as well. Especially for clerical work, there’s a lot of power that an individual supervisor or department might have over the work that you do. A lot of times, clerical workers will work more with their supervisors than they might with a coworker. We have a lot of members who, like me, were in a situation that was a pretty positive one. I was treated with respect on a day-to-day basis, and developed a lot of friendships and collegiality. But others weren’t, and as a union we could see big differences in how people would get treated.

We also knew that we do the behind-the-scenes work that allows faculty to do their research and teaching. Over the past 20 to 30 years, we’ve seen administrative salaries skyrocket as they tell us that they couldn’t afford living wages for people. We pushed back on that. We might be in support staff positions, but we have access to all of this information, all of this data, and we knew exactly what was going on.

I saw our work at the university as being a canary in the coal mine, holding the university accountable, being the voice of conscience. Why are people at the university paid $300,000 or more a year? Why are people making so much more than the government? This is a public service.

Stager: When you first started at the university and in the union, did you ever picture yourself where you are today?

Horazuk: I went to the new employee orientation, and I signed my membership card and leadership reached out right away and said get involved. It’s easy to get involved, become an activist, and dive in at the level that you want. There are some that maybe are gatekeepers, but I think most people really just want to see folks involved.

I was vice president for a couple of years through the strike in 2007. The first strike in 2003 was just clerical workers. The second strike in 2007 was clerical, technical, and health care workers.

It went on for three weeks and was one of the handful of strikes that occurred that year. There are some who would say that our strike in ‘03 was more successful than the strike in 07’ because we didn’t win all that we wanted to win. But we struck when no one else was doing it. We learned how to organize and we learned how to stand up together and created a community of workers.

I became chief steward from 2008 to 2012. I loved being able to solve problems for people and make people’s lives better on a day-to-day basis. And then Phyllis Walker, who was our president for quite a number of years, retired. A number of people encouraged me to run for president and I did. So I became president of the local in 2012 and was in that position until just last month when I resigned.

Stager: What’s next for you?

Horazuk: I thought I was going to retire from the university. I loved being a university employee and loved being active in my union and being a leader, but I got this great opportunity that I just couldn’t say no to. I’ve taken a position as senior campaign lead with the Association of Flight Attendants (AFA), helping to organize at Delta. Delta is the largest non-union major airline in the country. There’s an effort between Teamsters, the International Association of Machinists, and AFA to organize wall-to-wall. It’s the largest organizing drive in the country right now. Ninety-thousand flight attendants have contracts coming up that they’re in negotiations for right now.

Stager: I’m seeing a thread there—the work must be different from being at a big university, but there’s still globally-connected organizing and community there.

Horazuk: Most of my union life has been as a clerical worker. And you would think flight attendants are very different, right? But there’s a similar kind of mindset. What people are doing is incredibly important work that contributes to the institution or the company being able to function, and yet, it’s disregarded. It’s like, “oh, you just serve coffee. Oh, you just make copies.”

Stager: What does solidarity mean to you?

Horazuk: Solidarity for me is a profound concept that should guide your life and how you want to interact with others. At the heart of it is the idea that we have interests in common and that if we stand together, we can make this world a better place. I know that my interests as a worker in the United States have much more in common with a worker in El Salvador, or in the Philippines, or in Gaza, or in Greece, than with any company. There are so many people in power that want to divide us when in reality, we have so many things that unite us. It’s the working class that produces the wealth and we have power when we stand together.