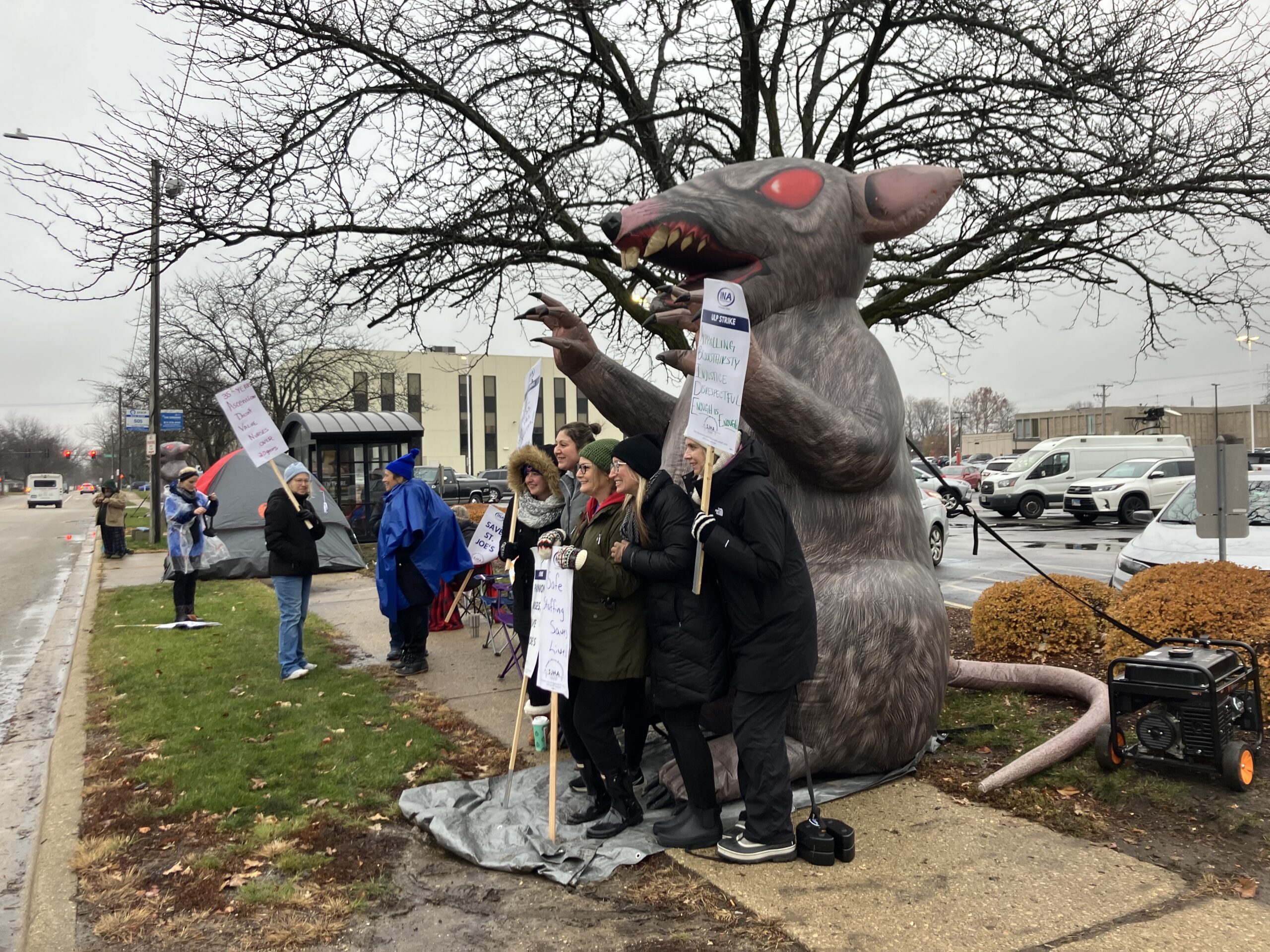

Nurses on the picket line pose with labor movement mascot Scabby the Rat outside Ascension St. Joseph Medical Center in Joliet, Ill., on November 21. Photo courtesy of Illinois Nurses Association.

Share

On October 6, a group of union nurses confronted the leadership of Ascension St. Joseph Medical Center in Joliet, Ill., also known as St. Joe’s.

Beth Corsetti, who has worked as a nurse for 10 years and has been at St. Joe’s for three of those years in the cardiac unit, raised concerns about unsafe staffing to president Christopher Shride, she says. “I asked, ‘how do you not see the fact that the amount of falls we’ve had and the amount of injuries that have been found is because we don’t have staff to get to these patients?’ And he flat out looked at me and said, ‘We have no staffing crisis,’ ” Corsetti says. “I still can’t get over it.”

Nurses say Shride continued to deny their safety concerns, and maintained that the hospital was not in violation of state staffing regulations. Meanwhile, the nurses also say Ascension, which is one of the largest private healthcare networks in the United States and acquired St. Joe’s in 2018, hasn’t budged at the bargaining table during union contract negotiations that have been ongoing for months, even after a federal mediator became involved after the nurses went on strike for two days in August, with Ascension locking them out for an additional two days. (When asked to comment on these events, Ascension did not immediately respond.)

The nurses began another two-day strike on November 21 after voting between October 24 and 26 to authorize as many strikes as it takes to secure a contract. “All we want to do is work in an environment that doesn’t feel actively dangerous,” says nurse Robyn Richards in a press release from Illinois Nurses Association (INA). “Ascension is trying to force us to agree to take on jobs we are untrained for and accept a pay scale that will continue to lose staff to nearby hospitals. We are striking because that just won’t work for this hospital or for Joliet.”

Previous reporting from Workday Magazine shows that nurses have alleged Ascension is breaking a new staffing law, the Nurse Staffing Improvement Act, which requires hospitals to have written safety plans, and gives the Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH) the ability to impose fines for failure to comply. Nurses at St. Joe’s have filed hundreds of Assignment Despite Objection (ADO) forms this year describing unsafe staffing levels, and are continuing to allege that the IDPH is placing both nurses and patients in harm’s way by failing to regulate according to the law.

A 2021 University of Pennsylvania study looking at nurse staffing ratios in Illinois found that thousands of deaths could be avoided, the length of patient stays could decrease, and hospitals could save money, if nurses were only assigned to no more than four patients at a time. “We have been heavily sending these IDPH complaints,” says Kaitlynd French, a nurse at St. Joe’s in the medical oncology unit and communications committee chair for the union. “They are not staffing for acuity, or how sick the patients are on the floor.”

French and her coworkers who have filed hundreds of complaints have been questioning whether or not IDPH is doing its due diligence investigating hospital safety when it comes to staffing levels. “You are serving the public, not these corporate, billion-dollar companies who do not have the public’s best interests in mind,” she says.

According to an IDPH spokesperson, the IDPH conducted a survey in February and found violations of staffing, after which they issued a notice of violation and a plan of correction. However, the IDPH says that an “unannounced” survey in October “found Ascension St. Joseph met the staffing by acuity regulations under state law by following the procedures as set in their plan of correction.”

Multiple nurses at St. Joe’s who have expressed skepticism told Workday Magazine that they feel the IDPH is not taking their complaints seriously and is failing to hold Ascension accountable.

According to INA, St. Joe’s has experienced a record number of falls this past year. “I found that out and it devastated me,” says Corsetti. “Management hovers instead of helping, and says we’re not doing good enough and we need to do better with less help.”

In addition to unsafe staffing, the nurses are concerned about Ascension potentially closing its labor and delivery unit. Ascension closed maternity units at St. Francis in Milwaukee, last year, at Mercy in Oshkosh, Wis., last month, St. Vincent in Jacksonville, Fla., earlier this year.

Union grievance chair Andi Miller, who has worked as a nurse in the labor and delivery unit at St. Joe’s for 26 years, says she has seen the staffing levels be chipped away over the years. “It’s a fear of mine that I’ve seen coming for a while,” she says of a potential closure. She says doctors and nurses would rather work at other hospitals like Silver Cross in nearby New Lenox, Ill., where they can be paid up to 10 to 15 dollars more an hour depending on years of experience. She says St. Joe’s incentive pay system for working overtime and picking up extra shifts helps, but she would rather have the hospital fully staffed.

“I’ve always loved my job at St. Joe’s, but they’re making me ashamed to work there now,” she says.

Voting to strike as many times as necessary to get Ascension to stop committing unfair labor practices and staffing the hospital dangerously low also allows nurses to coordinate with other Ascension facilities who are also facing unfair labor practices across the country, they say. “We are going to do what it takes for Ascension to realize they have messed with the wrong nurses,” says French.

The nurses say they hope that going on strike will get Ascension to raise wages and stop committing unfair labor practices.

“Something bad’s gonna happen. It’s a matter of when,” says Corsetti. “These are our patients. These are our families, friends, community. We’re not going to let them destroy us.”