Share

This story was originally published by ProPublica. ProPublica Illinois is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to get weekly updates about our work.

In the weeks before Norma Martinez died of COVID-19, she and her co-workers talked about their fears of contracting the coronavirus on the factory floor where they make and bottle personal care and beauty products, including hand soaps.

Rumors had been circulating among the workers — particularly those, like Martinez, who were employed through temporary staffing agencies -— that somebody at the facility in the southwest suburb of Countryside had tested positive for the virus or had been exposed to someone who had. Martinez, 45, told relatives she walked quickly and tried to hold her breath when she got close to other workers.

Some employees stopped taking shifts, worried about the risks of working elbow to elbow on tight factory lines or swiping in with their fingertips on biometric time clocks. But many more kept showing up, unable to afford to stay home and isolate.

“Norma went to work scared like all of us, but taking the safety precautions she could: washing hands, using gloves, wiping down machinery with rubbing alcohol,” said one of her co-workers, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of losing her job. “We weren’t OK with the factory still being open.”

Martinez, a Mexican immigrant and mother of two, died April 13. Her death came just days after the Voyant Beauty facility shut down for a deep cleaning after another employee tested positive for the coronavirus, according to several workers.

After Martinez’s death, her former co-workers, with the help of a workers’ advocacy center, went to the Illinois attorney general’s office, which has taken on the role of investigating workplace safety complaints from the private sector amidst the pandemic. The office is filling a void left by the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which has taken a largely hands-off approach to investigating coronavirus-related complaints from workers outside the health care industry, leaving employers to mostly police themselves.

Workers’ advocates and a group of Latino lawmakers say that they are grateful the attorney general’s office has taken on worker safety issues during this crisis, but that it’s a piecemeal solution, one that has led workers in some area factories to stage walkouts or other protests over safety related to the pandemic.

“It’s a Band-Aid for a flood,” said Tim Bell, the executive director of the Chicago Workers’ Collaborative, a nonprofit organization that focuses on temporary workers. He and others worry that more factory and warehouse workers will get sick and die unless the state establishes and enforces strong COVID-19 workplace safety rules at facilities considered too essential to shut down during the pandemic. “Given OSHA is still hiding under their desks,” Bell said, “there’s got to be something the state does to protect its residents.”

It’s unknown how many factory, food processing or warehouse workers have died of COVID-19 in Illinois. This weekend El Milagro, a popular Chicago tortilla maker, announced it would shut down for two weeks after one of its workers died from complications related to COVID-19. Martinez’s death was the first reported to the attorney general’s office. A spokeswoman for the Illinois Department of Public Health said the agency has some limited occupational data related to COVID-19 cases, but it is incomplete and not publicly available. The department, the spokeswoman said, is working on this issue.

But state officials recognize that workplace safety is a massive area of concern right now. So many complaints from workers have flooded the attorney general’s office that its workplace rights bureau has had to more than quadruple in size, pulling in attorneys from across the office.

“My understanding is that OSHA has taken the position … that they were not enforcing the CDC guidelines that were put out,” said Alvar Ayala, who heads the bureau. “That put a special urgency on this, and that’s where a lot of these organizations were coming to us and workers were coming to us for enforcement.”

In the past six weeks, the bureau has received more than 1,000 workplace safety complaints related to COVID-19, ranging from employers failing to maintain safe spacing on assembly lines to not conducting a deep cleaning of a workplace after a worker tests positive. Many complaints have come in Spanish and from employees in the manufacturing, food processing and packaging industries.

The attorney general’s office then works with local health department officials to conduct inspections of factories and warehouses to determine what changes, if any, are needed. So far, the office has not brought any lawsuits against manufacturers or other companies for violating workplace safety, though it has the authority to do so under state law and Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s March order on social distancing. The possibility of a lawsuit, officials said, has been enough to prompt compliance.

Mark Denzler, president and CEO of the Illinois Manufacturers’ Association, said he thinks local, state and federal agencies are doing their best when it comes to responding to workers’ safety concerns amidst an unprecedented situation. “Everybody is struggling to get a grasp of how to handle it, whether it’s the state, the city, OSHA, the CDC,” he said. “Certainly the AG is vested with certain powers to fulfill its job. The Department of Labor has powers to fulfil their jobs. Manufacturers are operating as safely as possible.”

A spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Labor, which oversees OSHA, said the agency “is diligently working every day to help employers understand and meet” their obligations to protect workers exposed to coronavirus at work. The spokesperson said OSHA has received a complaint regarding Voyant Beauty but could not provide further information until the investigation was complete. It’s unclear who filed the complaint or whether it is connected to Martinez’s death.

Former co-workers said Martinez had worked at Voyant for years through a temp agency, most recently in quality control.

Ann Miller, a senior vice president for human resources at Voyant, said the company was “heartbroken for this loss.”

She said the company had taken a number of safety procedures before hearing from the state, including daily temperature checks, issuing personal protective equipment to workers and sterilizing work areas daily. In addition, Miller said, the plant is shut down and deep-cleaned on weekends and in the event of a positive or presumed positive COVID-19 test.

The attorney general’s office, Miller said, had “no further suggested actions.” A spokeswoman for the attorney general’s office said the company had “agreed to comply with the governor’s executive order” just two days after Martinez’s death, but she did not explain what specifically the company agreed to do.

The office has not received additional complaints about the factory since then, the spokeswoman said.

Workers said the company had indeed made some changes at the facility to improve workplace safety in the weeks and days leading up to Martinez’s death. But they weren’t always effective. One worker said she passed daily temperature checks but discovered a few days after Martinez’s death that she was positive for COVID-19; she was an asymptomatic carrier. That worker also described being unable to wear a face mask at the site because it fogged up her safety goggles.

Bell’s group has been calling on Pritzker to enact new protections for temporary manufacturing and warehouse workers, including mandating 6 feet of spacing between workers, banning the use of biometric time clocks and requiring paid sick time for temporary workers.

Pritzker’s office did not respond to requests for comment. However, a modified stay-at-home order that the governor announced last week will require manufacturers and other essential businesses to provide face coverings to all employees who are unable to maintain 6 feet of social distancing and to take additional precautions such as staggering shifts and operating only essential production lines. The new order goes into effect Friday and is extended through May.

Meanwhile, a group of Latino lawmakers has also been pressing the governor to set clear safety rules and penalties for manufacturers. Among the requests: mandates to ensure proper social distancing and routinely disinfect common spaces; a requirement to shut down for at least 24 hours for deep cleanings after a confirmed COVID-19 case among workers; and a guarantee of two weeks of paid time off for workers who test positive.

“We urge you to send a forceful and unequivocal message to all businesses that putting workers at risk, regardless of their race, ethnicity, language or citizenship status, will never be tolerated in our State,” members of the Illinois Legislative Latino Caucus wrote in a letter last month. The issue is particularly pressing among Latino constituents, the lawmakers wrote, because many of those who work in manufacturing are Latino immigrants.

When the governor’s office responded, it told the lawmakers “what we already know,” said State Rep. Karina Villa, a Democrat from West Chicago, a city with a large manufacturing base. The email from the Pritzker’s office included information on how workers with COVID-19-related complaints could go to the state OSHA or to the federal OSHA or attorney general’s office.

“There are no changes. There were no guidelines or enforcement,” said Villa, who added that she has received complaints from workers at about a dozen factories and food production facilities about COVID-19.

Villa, the daughter of Mexican immigrants, said the issue hits her on a personal level because so many people in her own life work in factories in the Chicago suburbs. She said one close relative who works at a meat processing facility in St. Charles recently tested positive for COVID-19. The Kane County Health Department temporarily shut down that plant Friday over concerns about COVID-19. (The state’s Public Health Department said it is working to formalize guidance for meat and food processing facilities, where it has identified clusters of COVID-19 cases.)

Villa and other advocates said they are particularly worried about temporary workers, who are disproportionately Latino; some 42% of the state’s more than 675,000 temporary workers identified as Latino, according to a state audit of temp agencies from July 2019.

Many are also undocumented, which makes them ineligible for unemployment benefits and federal stimulus benefits. That leaves many workers financially vulnerable, prompting them to return to workplaces where they feel unsafe, advocates said. During a Facebook live interview Monday with Univision Chicago, Pritzker said his administration is looking to create some type of cash assistance program for undocumented immigrants who don’t qualify for federal benefits. California Gov. Gavin Newsom announced this month a private-public partnership to put cash in undocumented residents’ pockets amidst the pandemic.

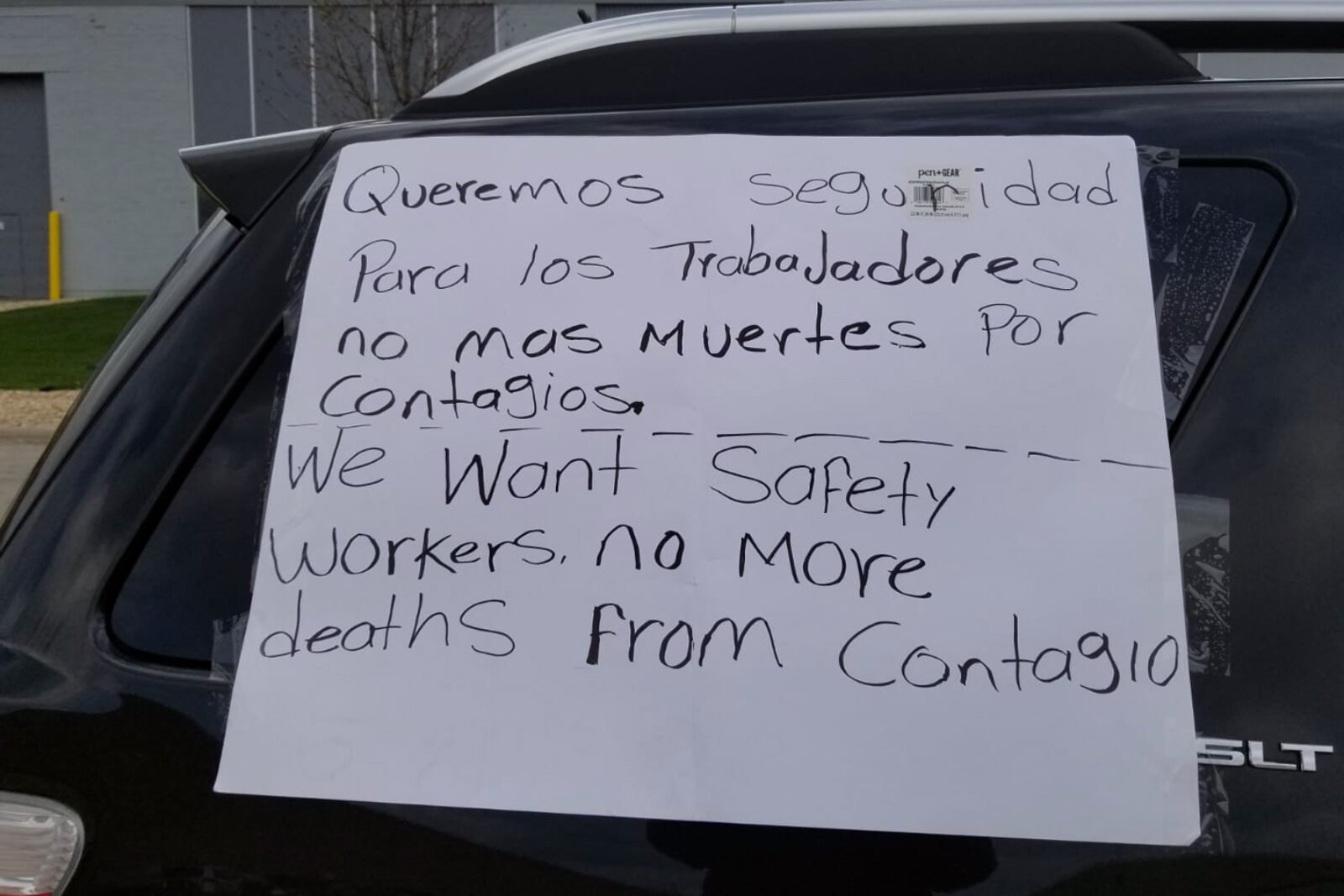

At Voyant, the news of Martinez’s death convinced some of her former co-workers to stay home or get tested for coronavirus themselves. The day after she died, former co-workers staged a car caravan protest in her memory in front of the factory. About 10 workers showed up, taking turns slowly driving past the entrance and honking. Some had signs on their car windows. “We want safety for the workers,” one sign read. “No more deaths from contagion.”

The death was sudden, said one relative who lives in the same house as Martinez’ family. She died at home in the early hours of April 13, according to the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office. At least one other family member got sick, the relative said. They were still in shock and grieving her loss.

The relative recalled how Martinez worried about keeping her children safe from any possible infection she brought home from work. As soon as she entered the house, she stripped her work clothes off and showered. “She wouldn’t let her children get too close,” the relative said. “She was afraid to hug them.”

Duaa Eldeib and Jodi S. Cohen contributed reporting.