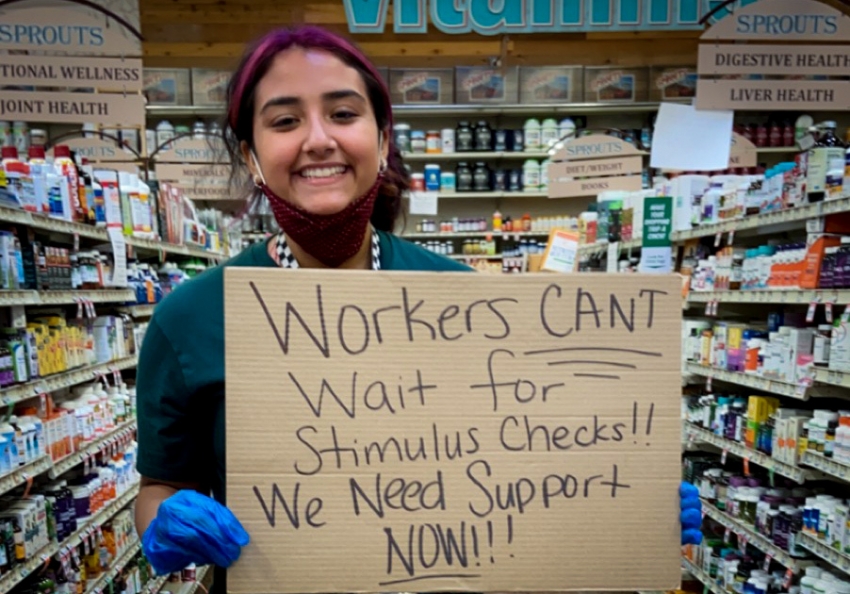

A worker at the Sprouts Farmers Market in McAllen, Texas, protests for hazard pay and coronavirus-safe working conditions. (Courtesy of Democratic Socialists of America)

Share

As shoppers crowded into the McAllen, Texas, branch of Sprouts Farmers Market in mid-March to stockpile food, store clerk Josh Cano grew alarmed at the lack of safety precautions in place.

“There weren’t sneeze guards or masks or gloves,” he says. “There was zero sense of urgency from management.”

Cano, 24, worried about bringing the coronavirus home because his mother has cancer and is undergoing chemotherapy. He had heard of an online form that activists from the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) and the United Electrical Workers union (UE) were using to help workers organize to make their workplaces safer as the COVID-19 pandemic spread. The two groups—which had previously worked togetheron the Bernie Sanders campaign—were calling their joint effort the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee (EWOC).

The experience many EWOC organizers gained from the Sanders movement had a direct impact on their work. Officials from the DSA and UE said the group took ideas from the Sanders campaign—such as building a largely volunteer operation to do complex organizing—and applied them to workplaces rather than an election. Many former Sanders staff members also volunteered to help workers organize. It’s one example of a possible path forward for the grassroots movement that powered the Sanders campaign—a way to channel its insurgent energy into new battles for social justice.

Cano filled out the form, and Michael Enriquez, former deputy field director of the Sanders campaign in Iowa and a member of the EWOC planning committee, responded to assist the Sprouts workers. With guidance from Enriquez, who previously ran the Fight for $15 office in Kansas City, Cano and a co-worker, Michael Martinez, soon got 44 of their store’s 50 workers to sign a petition demanding personal protective equipment, a $3 an hour increase for hazard pay, 14 days of paid sick leave and an in-store safety committee. “We started the petition out of fear,” Martinez says.

On the afternoon of April 1, six Sprouts workers marched on their boss’s office with their petition and protest signs saying, “Health and safety over profit,” and “Make the pay worth the risk.”

The workers wanted outside support, and with Enriquez’s help, they got the petition circulated through Change.org. Within a week it had 7,000 signatures, including workers from some of Sprouts’ 340 other stores. A huge boost came when Sanders himself tweeted his support for the Sprouts workers.

“Seeing that tweet made me and my coworkers feel we weren’t alone,” Cano says. “We were kind of scared about management. Seeing that tweet, we saw we had a lot of power on our side.”

Feeling heat from the petition, Sprouts agreed to provide masks, gloves and more sanitizer and to limit the number of customers inside the McAllen store at any one time. The workers hailed it as a victory, even though management refused to provide hazard pay. “There’s no power like workers united,” Martinez says. He adds that Enriquez’ expertise was “instrumental in our success.”

Colette Perold, a DSA activist and member of the EWOC planning committee, explains the project began when some DSA members started hearing from friends worried about the dangers at their jobs. “They were being forced to do a lot of dangerous things,” she says. So the DSA and the United Electrical Workers decided to reach out to workers. “The campaigns that workers are leading in their workplaces are life or death fights, and we want to support that self-activity and help them win,” Perold says.

Mark Meinster, an international representative with the United Electrical Workers, says his union helped form EWOC because “we’re seeing so many workers take risks to protect their own lives.”

“Unions have a choice right now,” he says. “We can either hunker down and ride out the storm, or we can get on the side of the workers in struggle, many of whom are nonunion workers. If we can help workers wage a broad, militant fight back, we can hopefully set the stage and make some changes in society for the common good.”

Since launching in early March, EWOC’s organizers have helped several hundred workers fight for improved safety at warehouses, fast-food restaurants, hospitals, bottling plants, supermarkets and childcare centers across America.

Dani Shuster, a cashier and customer service worker at a Mom’s Organic Store in Philadelphia, says she is thankful for the advice the workers at her store received from EWOC. For two weeks in early March, panicked shoppers flooded the grocery. (One day, Shuster says, actress Kate Winslet entered the store wearing gloves and filled up four shopping carts.) Many workers were putting in 10- or 12-hour days to meet the surging demand.

“A lot of workers expressed fear, anxiety, feelings of being overwhelmed, and we were hearing nothing from the corporate leadership,” Shuster, 29, says. Workers complained that Mom’s — a chain with 19 stores in four states and Washington, D.C. — was not providing masks and that there wasn’t enough hand sanitizer throughout the store.

“We just seemed to be abandoned by the people in power,” Shuster says. “We started to conclude we needed to do something.” Although she had no prior experience in workplace organizing, she was inspired by the message of the Sanders campaign. “The realization that our collective power can challenge corporate greed and we can win helped make the possibility of organizing in my own workplace a reality.”

After surveying their coworkers, Shuster and several colleagues plunged into drafting a list of demands and a petition. At that point, Shuster, recognizing she could use some organizing advice, reached out to EWOC, which she had heard about through an acquaintance in DSA.

Shuster says that EWOC felt like a “natural” outgrowth of the Sanders campaign. “In my own experience and observations, the Sanders campaign helped reignite worker organizing in this country,” she says.

Dan advised her on how to get coworkers to sign a petition; its demands included hazard pay of time and a half, a midday break for sanitizing, and limiting the number of customers in the store to 20 at a time. “Dan helped me feel confident in having direct conversations with workers and really posing the question, ‘Are you willing to sign this petition to protect your own life and the lives all around you?’” Shuster says.

Nineteen of the store’s roughly 33 workers signed, and Shuster presented the petition to store management with six coworkers on April 6. They then held a protest outside the store as a caravan of supporters drove around honking. (Many supporters came from a community group, OnePennsylvania.) Management did not respond immediately, although the grocery says it stepped up cleaning procedures and installed protective plexiglass at the registers.

In the days after the protest, the workers grew increasingly impatient, and pressure on Mom’s grew. The Pennsylvania Attorney General’s office even got involved, holding meetings with organizers and, Shuster says, contacting the CEO of Mom’s. Mom’s ultimately provided masks and more sanitizer and agreed to set customer limits in sections of the store. It also said it would institute a special shopping hour for seniors and vulnerable populations — something the Mom’s workers had demanded. Management also agreed to a retroactive bonus, though it disappointed the workers by refusing to grant regular hazard pay.

“We saw what happens when you speak out individually—not much,” Shuster says. “We demonstrated that when workers come together, they can accomplish a lot.”

Asked about forming a union, Michael Martinez of Sprouts says, “A labor union, that’s not what we’re going for. We’re trying to show that the workers have strength in numbers and that we won’t accept the bare minimum.”

The UE’s Meinster acknowledges that what EWOC is doing is not typical union organizing. “These are immediate fights around immediate demands,” he says. “The kind of tasks confronting the labor movement is to provide support and leadership to those workers and help develop the workplace leaders we’ll need in coming years.”

This article first appeared at In These Times