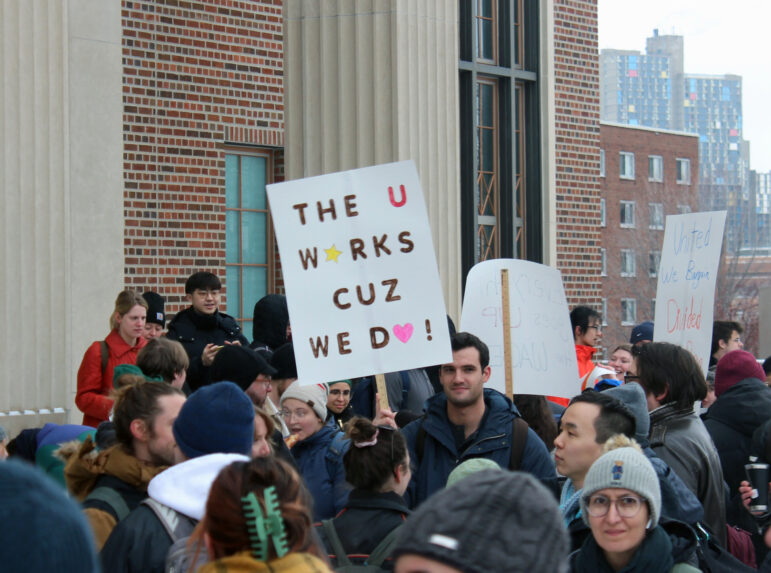

On February 20, a crowd of graduate workers and supporters form for a rally outside Coffman Memorial Union to announce union drive. Photo by Amie Stager.

Share

“Me and my colleagues across the board were overworked, underpaid, and really feeling the effects of that to the point that it was making it really difficult to do the stellar work that we like being here to do and we want to do,” says Phoebe Keyes, a third year Ph.D. student in civil, environmental, and geo-engineering at the University of Minnesota (UMN).

Now, Keyes is part of an effort to change that. On February 20, Keyes, among other fellow graduate workers at the Twin Cities campus of UMN, announced their union drive in front of the Coffman Memorial Union. The workers were supported by a high-energy crowd of several hundred students, community members, city councilmembers, and labor movement leaders. In one passionate speech, Chiara Amato, a Ph.D. student in Aerospace Engineering and Mechanics, described graduate workers as the “silent labor that keeps the university running,” as dozens of student workers signed their union cards at a table nearby.

The UMN Graduate Labor Union, or GLU-UE, says that, by one month after the card-signing drive began, more than 2,800 cards were signed, meaning over 65% of the graduate workers indicated support for a union. According to a press release from the union, more than enough cards have been signed to move to a vote, and prospects look good. There are over 4,300 graduate workers in the bargaining unit—however, the exact number fluctuates from semester to semester.

Amie Stager

On February 20, a crowd of graduate workers and supporters form for a rally outside Coffman Memorial Union to announce union drive. Photo by Amie Stager.Graduate workers labor as teaching assistants and research assistants, depending on their department, across the university for about 20 hours a week, along with pursuing their own research and taking classes. As TAs and RAs, graduate workers have a range of tasks, including supporting professors in labs, grading undergraduate students’ coursework, teaching classes, giving lectures, and supporting undergraduates in office hours.

The University of Minnesota has stated that the average stipend is $19,609 for a 9-month appointment. A GLU-UE representative added that while summer support is an option for students, it is often unpredictable and cannot be guaranteed.

The graduate workers affiliated with the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE) in part because of the unions’ historical commitment to rank-and-file leadership, and its recent successes with organizing academic unions nationally. This includes graduate workers at the University of Chicago, who recently won their union election with a 92% margin of victory.

Why UMN Graduate Workers Want a Union

Keyes explains that the students behind this organizing drive attempted other ways of making change, including a petition last year, signed by 50% of graduate workers, asking for a minimum $35,000 annual stipend. However, this petition did not result in real, lasting improvements for the graduate workers, they say. “It seems like the only option to get real, tangible improvements for grad students is to come together, work together, and unionize,” Keyes explains.

Graduate workers say they are concerned about low pay and unaffordable student fees. They are calling for additional support for international students, and improved accountability structure with direct supervisors.

“People are living well below the living wage in Minneapolis,” says Keyes. “People usually pay about a paycheck a semester on the student fees. It’s just becoming unlivable.” In 2021, the living wage for a single adult in Hennepin County was estimated to be $37,025 per year for full-time work.

Graduate workers are paid different rates depending on their area of study, with science, technology, engineering, and mathematics departments on the higher end of the pay spectrum, and humanities on the lower end. Yusra Murad, a first-year public health Ph.D. student, says that the pay disparities between departments are “completely antithetical to so many of the principles and values that we like to have as a university of equal opportunity. It creates this false hierarchy between students.”

International graduate workers are often unable to supplement their stipends with outside employment, and must pay higher fees to the university, graduate workers say. One international student, Dani Arruda, a second-year graduate worker in Kinesiology, explains that “because of my visa, I can only work 20 hours a week and cannot find any work outside the university to supplement my income. On top of this, the university charges additional international student fees that domestic students do not need to pay, creating an unfair and discriminatory burden on thousands of international students.”

Amie Stager

Yusra Murad, first year public health PH.D., speaks in front of the rally on why she wants a union for graduate workers. Photo by Amie Stager.Graduate workers are also concerned about the power and accountability structure at the university, and relationships with advisors. Due to the highly specialized nature of many students’ areas of study, Murad explains that advisors hold a lot of power. This puts some students in “a precarious position” that can vary greatly depending on the relationship and culture of the department. Students’ advisors may be the only or one of very few people in the country doing the same research. “The advisor has a lot of power over their future careers so that can be a big challenge,” says Murad, “and it can be a situation that is ripe for abuse.”

She says that while some students may have positive relationships with advisors, all could benefit from formal protections, rather than individual reliance on the good will of advisors.

But within this environment, Murad says, “there has been such an effective mischaracterization” of graduate workers as merely students, in spite of all the labor they provide the university. “The idea that has been instilled in us is that graduate school is supposed to be hard, and you’re supposed to struggle, and you’re supposed to not make money… You should just be grateful to be here.” Some graduate workers may not see themselves as workers for the university, instead viewing their struggles as a necessary sacrifice towards their greater career goals.

Past Organizing Cycles

This campaign is preceded by several decades of organizing by graduate workers and various union and other organizing drives. The most recent attempt to win a graduate workers’ union was in 2012, when 62% of graduate workers voted against unionization. There were also unsuccessful unionization drives in 1974, 1990, and 1999. However, current and past graduate workers see these past failures as necessary cycles that allowed them to learn and build.

Kristi Wright, a former graduate worker of the University of Minnesota, was a leader of a graduate worker organizing movement on campus in the mid-2010s. Wright explains that that was a very different political moment, when “labor was on the defensive”—just off the heels of the inauguration of former President Donald Trump and the several conservative, anti-union appointees to the National Labor Relations Board.

Wright stresses that it was at a time when students faced an uphill battle, including organizing against a federal bill that would have classified graduate worker’s tuition reductions as taxable income, causing tremendous financial strain on already low-earning student workers. Wright and other organizers were able to turn out several hundred students to demonstrate against the bill, and ultimately it did not pass. But, Wright says, the incident shows the very different, defensive environment graduate workers were organizing under as recently as 2017.

Amie Stager

Graduate workers hold up signs in support of a union at the February 20 rally. Photo by Amie Stager.Organizing graduate workers is unique in that turnover is inherent to its structure and can be a challenge for long-term change to be passed over from generation to generation. Wright says generational cycles of organizing are vital for organizing long-term, and allow future generations to build back on past organizing. “There’s a lot of institutional memory that gets lost between these kinds of cyclical organizing drives every couple of years,” says Wright. “We spent a lot of time just trying to figure out what happened before us.”

Fast forward six years, and the University of Minnesota graduate workers find themselves in a very different climate—after a global pandemic and in the midst of a wave of unionization in higher education and other industries, including service, media, nonprofit, tech, and cultural institutions. Graduate workers today are in an era when people are rethinking and redefining their relationship to labor, and union sentiment is growing, even if union density is not.

National Trends in Higher Education Unions

In the past year, higher education union campaigns have been booming. Graduate workers at the University of Chicago, Yale, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Northwestern University, Boston University, Princeton University, and Johns Hopkins University, have announced union drives in 2022 and early 2023, indicating an ongoing and historic wave in higher education unionization drives. Murad is excited by these trends and hopes that the graduate workers at the University of Minnesota can “ride the wave of victories” and capitalize on the national momentum.

Graduate workers are also flexing their collective power for improving contracts. In the fall of 2022, University of California, Los Angeles graduate workers organized a 40-day strike, the longest academic strikes in United States history, winning wage increases of up to 80% for some of the lowest paid workers. This historic strike inspired graduate workers across the country to not only organize a union, but also demand more in existing contracts.

While there have been many victories in higher education unionization, this sector has also faced backlash. At Duke University, the administration is challenging the notion that graduate workers are in fact workers under the National Labor Relations Board’s definition. This most recent precedent was set in a 2016 case regarding Columbia University graduate workers where the NLRB decided that graduate workers at private universities met the definition of employees, and thus, can form a union. One student involved with the Duke University Students Union described the university’s decision to challenge this precedent as disappointing and “taking the nuclear option.”

While the University of Minnesota has issued public statements of neutrality, many graduate workers are not entirely trusting, in light of the fact that the university’s administration has tried to block unionization efforts and other organizing campaigns before.

The University of Minnesota is under the jurisdiction of the Minnesota Public Employer Labor Relations Act, or PELRA, the law that gives public sector workers in Minnesota the right to organize and form a union. The UMN graduate union and the university are currently working to determine the parameters of the bargaining unit.

Provost Rachel T.A. Croson and Vice Provost and Dean for Graduate Education Scott Lanyon recently told students in an email on March 20, “Over the next few weeks, we will work with the Bureau of Mediation Services to determine which positions are eligible under state law to be represented, who the eligible voters are, and the details of the election. After the terms have been solidified, we will share details with graduate assistants on the voting process.”

Moving Toward the Vote

The graduate workers are distributing a petition asking UMN staff and faculty to remain neutral throughout the election process. The petition states, “We believe it is institutionally, procedurally, and legally advisable that faculty maintain an official stance of neutrality and non-intervention on the issue of graduate unionization.”

Along with the petition, UMN graduate workers are also circulating a “Vote Yes Pledge”, in order to gauge support among the eligible voters in preparation for the election.

The union election date has not been set yet, but a GLU-UE representative said that the union “wants to hold the election as soon as possible.”

Amie Stager

A sign at the February 20 rally reads “UMN runs on grad students”.In the meantime, GLU-UE has been continuing to organize and speak to students in every department to understand what specific issues they may be facing. Keyes shared that these one-to-one organizing conversations, department by department, have been vital in organizing the union thus far, and have allowed graduate workers to feel heard and address the specific concerns they have.

It can be painful to hear about what some students are going through in order to continue their education, says Keyes. The financial burdens of continuing their education make it “extremely difficult for them to be able to thrive and live and cause a lot of mental health crises. A lot of people are dropping out when they should be able to stay in academia and pursue their Ph.D.s, but they can’t for financial or mental health reasons.”

Graduate workers are not simply fueled by grievance and anger, says Murad, but also by the love of the work they do. “We’re here because we want to be here and because we think our research is important, that it matters. And we want to stay. This comes from not just anger and frustration, but also love for the community that we have and commitment to the work that we are engaged with.”